The Missing Igniters: Fatigue & Management of Change Shortcomings

On 15 September 2015 the UAE General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) issued their investigation report into a Serious Incident that affected both engines of a Dash 8.

Their report highlights the importance of Management of Change both at a macro level, when undertaking corporate restructuring (highly topical for air operators in the oil and gas sector with $50 / barrel oil) and at the micro level, when introducing new tasks. It is also the latest of a series of investigations to discuss maintenance personnel fatigue and alertness.

The Incident Flight

On 9 September 2012, Bombardier Dash 8 / DHC-8-315Q A6-ADB, operated by Abu Dhabi Aviation and chartered by a local oil and gas company, departed Abu Dhabi International Airport on a scheduled 35 minute passenger flight to Das Island, about 100 nm away and home to multiple oil and gas facilities. A crew of 3 and 46 oil and gas workers on board.

Das Island

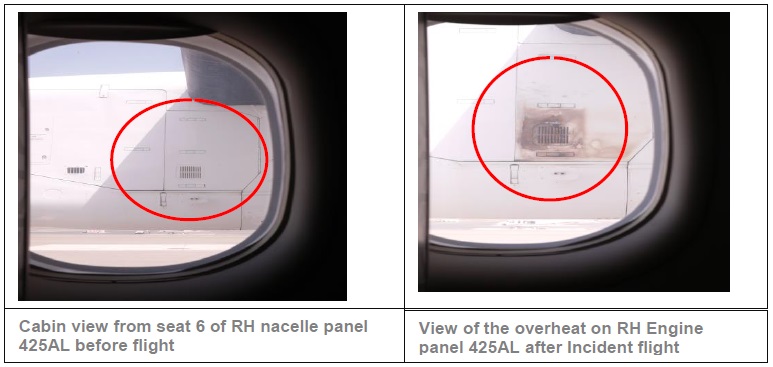

Several minutes intro the flight, a concerned passenger informed the cabin crew member about paint blisters forming on the right hand engine inboard cowling. Although no fire warnings were generate the crew decided to return to the international airport and landed 10 minutes after take off. It was only after a safe landing that it was discovered that similar damaged had occurred on the left hand engine outboard cowling too.

The engine cowlings were damaged because of:

…of hot engine gases escaping through an open igniter boss on the engine casing. The hot gas was impinging on the nacelle, engine case drain line and engine support strut.

The Maintenance History – Management of Change at the Micro Level

The operator has suffered from unscheduled engine removals due to environmentally induced performance deterioration. Several engine wash options are available for the Pratt & Whitney Canada PW123. The operator had been conducting turbine washes since May 2009. Until December 2011, these were conducted using a task card, that contained technical instructions and was used to record the sign-off by both mechanic and certifying engineer.

However to “reduce paperwork” and “improve process efficiency” these were replaced by a procedure that described the task and required a technical log entry, signed just by the certifying engineer.

In July 2012 supervisors locally, without reference to management, decided to trial doing a compressor wash at the same time as a turbine wash on one engine.

As the investigators note, unfortunately the trial was briefed verbally and inconsistently and conducted in an even less controlled manner than the compressor washes as:

…the work was being performed based on experience alone, and without any referral documentation from the AMM [Aircraft Maintenance Manual] to perform the physical task. In addition, the work was being conducted without any sign-off by the mechanic, or the engineer, and without any updates being entered into the electronic data system of the Operator.

They go on to report that:

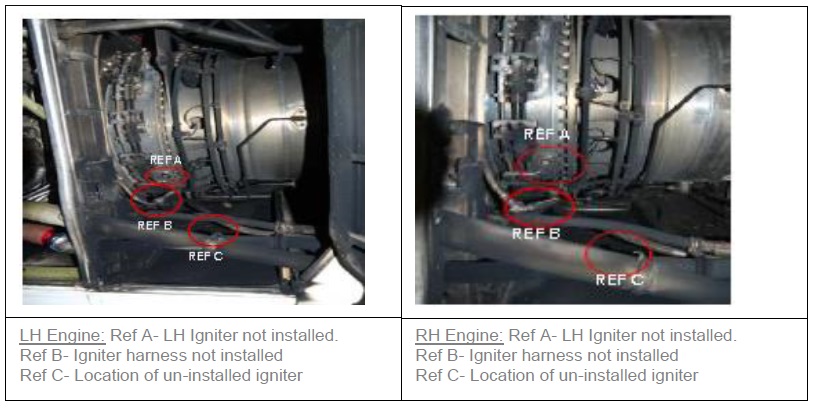

On the night prior to the Incident flight, the duty Engineer in charge of the shift had physically prepared both engines for turbine washes… He removed engine access panels 415AL and 425AL, the igniter leads and the left igniter from each engine.

The removed igniters were left inside the recess of the engine compartment without placing them in protective bags.

The duty Engineer returned to the ‘control office’ where he proceeded to update the electronic data system for work done inside the hangar. He allocated two mechanics to perform the engine washes on the aircraft.

The investigators note:

This instruction was verbal, without specifying what engine wash was required, and the Engineer did not mention that the engines had already been prepared for the turbine washes.

The mechanics …were not sure whether or not the turbine washes also had to be performed on the Aircraft, and they concluded that only the compressor washes were required.

The GCAA do not comment on why this uncertainty did not result in seeking clarification.

Meanwhile the aircraft had been towed outside and the two panels were both closed. There were no paperwork entries or visual reminders (such as cockpit signs or ‘streamers’) to highlight the disassembly.

They proceeded to compressor wash both engines (even though the trial was on one). This did not require panels 415AL and 425AL to be opened.

At no time during this wash sequence was any aircraft manual referred to”.

Both mechanics returned to the control office around 1 hour before the end of shift and verbally informed the Engineer that the engine washes were completed. The assumption made by the Engineer was that the mechanics were referring to the completion of the turbine washes. He was unaware that the mechanics had actually performed compressor washes on both engines…

The Engineer…[did not] physically verify that the engine igniters were normalized after the washes before signing off the work in the Aircraft maintenance log book.

Unfortunately the GCAA were unable to determine why the Engineer did that without verification. They do note:

- His confidence in the mechanics.

- The closeness of the time to the end of the shift.

- Cumulative fatigue (discussed further below)

- The distraction of entering electronically entering data in a new software system seemingly introduced with minimal training.

However wider practices such as verbal-only briefings, simplifying paperwork and working without reference to maintenance data were latent system pathogens.

Organisational Change – Management of Change at the Macro Level

The investigators report that:

Prior to 2008, over 800 personnel were employed by the Operator. This number included approximately 150 aircraft maintenance engineers. However, in 2008/2009 [at the time of the global financial crisis], the Operator underwent a company-wide restructuring which resulted in a reduction in headcount, including production staff supporting aircraft maintenance.

This restructuring also reduced the staffing of the Safety Department and placed the safety functions under the Quality Department. The Quality Post Holder then assumed the overall SMS [Safety Management System] responsibilities. As indicated by the Operator during this Investigation, management of change associated with the reduction in staff was not performed.

The investigators note that Management of Change became part of the GCAA SMS regulations (CAR Part X) in 2012 and state that:

Whenever a company decides to carry out staff reduction especially those that are involved with safety sensitive tasks, there should be a careful and well-structured approach to ensure that safety is not jeopardized. Detailed risk mitigation should be implemented and safety nets, as required, are to be put in place before the decision of staff reduction. The same actions can also be applicable for staff increase as well as when temporary staff is employed. For the Operator’s implementation with staff reduction, the Investigation could not determine if this was discussed with the GCAA.

Furthermore another organisational change was introduced at the request of the regulator:

In May 2011, the GCAA raised an audit non-conformance that required Safety to be independent from Quality. In August 2011, in response to this non-conformance, the Operator appointed a new SMS postholder who was subsequently accepted by the GCAA in September 2011. A new Safety Department was created which marked the commencement of the SMS Planning and Implementation to comply with the GCAA requirements.

Although the local regulations (CAR Part X) had required an SMS by 31 December 2010, the GCAA subsequently accepted that the SMS Manual could be submitted for approval by the end of 2012.

The investigators report that an internal audit in May 2012:

…brought to the attention of the Operator’s senior management nonconformities related to SMS implementation, staffing issues within the Safety department, risk assessment not defined, safety hazard identification, safety audits and flight data monitoring.

Additional safety staffing was finally introduced in January 2014.

The investigators indicate that internal and regulatory audits had not seemingly attended to issues of maintenance standards in sufficient depth. They also note that while the operator had conducted a safety culture survey of flight crew in 2011, nothing similar had been done for maintenance personnel.

The investigators give the impression that organisational changes may have both increased the risk of maintenance related occurrences and weakened the capability to manage that risk.

Fatigue and Alertness

Most of the maintenance personnel were working a 56 days on / 28 days off shift pattern with no intermediate rest days. At the time of the pre-incident maintenance, the duty Engineer for example, was on his 32nd consecutive day of work and had also worked 3.5 hours overtime the day before. The investigators mention two ‘rest days’ but these were changes from early to late shifts and back, so had no effect on the total work in a 24 hour period.

We have previously discussed maintenance fatigue:

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors: when shifts were changed at short notice and personnel worked over 12 hours to complete a check

- A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Report: when an undermanned night shift team was working excessive overtime

There is also a useful 2002 UK CAA research paper: CAA Paper 2002/06: Work Hours of Aircraft Maintenance Personnel prepared by Simon Folkard DSc., Body Rhythms and Shiftwork Centre,

Department of Psychology, University of Wales (aka ‘The Folkard Report’),

While fatigue, and a consequential lack of awareness, may have affected several of the personnel involved they say:

…it is not confirmed to what extent the accumulated fatigue would have influenced the maintenance error.

The investigators discuss a wide range of fatigue guidance and regulation, but note that UAE regulations do not address fatigue of maintenance personnel (the subject of one recommendation).

Human Factors Training

The investigators state that:

The Engineer and the mechanics who carried out the maintenance work on the Aircraft completed human factors and CAR-145 training as documented by the Operator. Thus, they were aware of the health and safety elements affecting their performance as well as the requirement of recording and sign-off for work performed on an aircraft.

In spite of this training, this Incident involving omission of installation of a critical part was an error waiting to happen from the inception of the uncontrolled engine washes that started in July 2012.

It is not surprising that one recommendation made in the report was to examine the practical implementation of human factors and SMS training. Again we observe that managing human factors requires more than simply awareness training. It needs both a commitment to actively manage human performance influencing factors and a culture were mindful improvement is normal behaviour.

Recommendations

The operator has made a number of changes in the 3 years since the incident. In their report the investigators make 8 recommendations to the operator. Another 6 are directed at the GCAA itself.

Maintenance Human Factors Resources

Aerossurance is proud to have sponsored a recent Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group: Engineering (HFG:E) seminar, Maintenance Human Factors: The Next Generation, at Cranfield University. In his opening address Professor Dave King (a former Chief Inspector of Air Accidents at the UK AAIB) highlighted that as well as thinking about the next generation in the industry we also need to think about a next generation approach to human factors in engineering. Presentations from that seminar are available here.

Aerossurance has previously written about a number of relevant safety, human factors and continuing airworthiness issues:

- Professor James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors

- Inadvertent Fire Bottle Discharge During Maintenance

- FOD Damages 737 Flying Controls

- Cessna Citation Excel Controls Freeze

- B767 Engine Fire – Ignition from Misrouted / Chaffed Cables

- A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Report

- Loose B-Nut: Accident During Helicopter Maintenance Check Flight

- USAF RC-135V Rivet Joint Oxygen Fire

- UPDATE 24 June 2018: B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices

- UPDATE 22 July 2018: Fire After O-Ring Nipped on Installation

- UPDATE 25 August 2018: Crossed Cables: Colgan Air B1900D N240CJ Maintenance Error

- UPDATE 16 March 2018: USAF F-16C Crash: Engine Maintenance Error

- UPDATE 13 November 2018: Inadequate Maintenance, An Engine Failure and Mishandling: Crash of a USAF WC-130H

- UPDATE 18 December 2018: USAF Engine Shop in “Disarray” with a “Method of the Madness”: F-16CM Engine Fire

- UPDATE 27 December 2018: Inadequate Maintenance at a USAF Depot Featured in Fatal USMC KC-130T Accident

- UPDATE 30 March 2019: Contaminated Oxygen on ‘Air Force One’ Poor standards at a Boeing maintenance facility, potentially fatigue related, resulted in contamination of two oxygen systems on a USAF Presidential VC-25 (B747).

- UPDATE 12 October 2019: ATR72 VH-FVR Missed Damage: Maintenance Lessons Unclear communications, shift handover & roles and responsibilities, complacency about fatigue and failure to use access equipment all feature in this serious incident.

- UPDATE 15 March 2021: ATR 72 Rudder Travel Limitation Unit Incident: Latent Potential for Misassembly Meets Commercial Pressure

- UPDATE 25 May 2025: CHC Sikorsky S-92A Seat Slide Surprise(s)

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help learning about routine maintenance and then to initiate safety improvements:

Aerossurance can provide practice guidance and specialist support to successfully implement a MOP.

Aerossurance is also pleased to be sponsoring the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors‘ Human Factors in Aviation Safety conference at East Midlands Airport 9-10 November 2015.

Aerossurance sponsored an RAeS HFG:E conference at Cranfield University on 9 May 2017, on the topic of Staying Alert: Managing Fatigue in Maintenance.

Aerossurance is pleased to be both sponsoring and presenting at a Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group: Engineering seminar Maintenance Error: Are we learning? to be held on 9 May 2019 at Cranfield University.

Recent Comments