Multi-Tasking Managers & Deficient Operational Control: Low Viz Take-Off Accident (Midtnorsk Helikopterservice AS350B3 LN-OBP, Norway)

On 1 November 2022 Airbus AS350B3 LN-OBP of Midtnorsk Helikopterservice crashed shortly after take-off at Slottelid (ENVS), Verdal, Trøndelag County, central Norway. The two passengers on board died. The pilot was seriously injured. A pet dog aboard also survived.

Wreckage of Midtnorsk Helikopterservice Airbus AS350B3 LN-OBP (Credit: NSIA)

The Norwegian Safety Investigation Authority (NSIA) published their safety investigation report on 5 December 2023.

The Air Operator ad Pilot

The operator was founded in 2002 and at the time of the accident operated one AS350BA, the AS350B3 and an EC120. They employed 8 people.

The pilot had 6,115 hours total experience, 3,800 on type. He held 4 positions within the operator; Accountable Manager, Compliance Monitoring Manager, Safety Manager and Deputy Manager of Flight Operations. The later potion was necessary because the Manager of Flight Operations was a retired fixed wing pilot, with no flight experience on rotorcraft. The Manager of Flight Operations and Technical Manager were part time employees, the former running a human factors & CRM business.

The Accident Flight

The plan was to transport two passengers, a dog and cargo from the operator’s base Verdal to a mountain farm in Snåsa.

Two days before the accident, the pilot had tried to fly the passengers to the farm, but had to abort due to fog in the mountains. The day before the accident there was fog in Verdal that prevented a flight.

On the day of the accident the morning fog lay low in the terrain in Verdal, and followed the valley and river.

The fog varied in density and two other company pilots had departed about 08:15 after a delay.

The passengers due to travel on LN-OBP arrived at around 09:00. The pilot loaded their baggage / cargo and waited for the visibility to improve.

The pilot told investigators “there was a calm atmosphere and that he did not feel any stress”.

Midtnorsk Helikopterservice Airbus AS350B3 LN-OBP at 10:03 Shortly Before the Accident Flight (Credit: via NSIA)

The pilot told investigators the fog had started to lift to the north east. He intended to take off in that direction, flying around a small cluster of trees near the landing site.

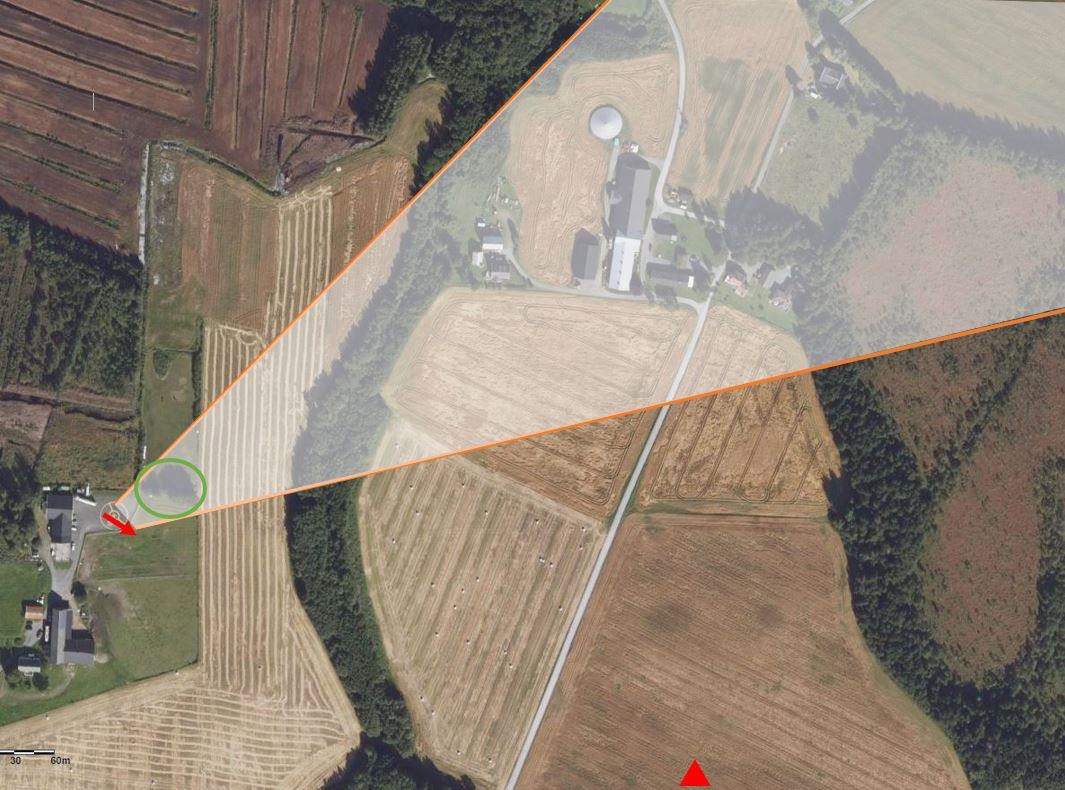

Map drawn based on a sketch by the commander of where he perceived an improvement in the weather (shaded area). The direction the helicopter was facing before take-off (red arrow), a cluster of trees close to the helipad (green circle) and the accident site (red triangle) are indicated. (Credit: Norwegian Mapping Agency & NSIA)

The pilot to a photograph looking north east though the cabin at c 10:30. Also evident is a large amount of unrestrained cargo.

Midtnorsk Helikopterservice Airbus AS350B3 LN-OBP: Photo taken by the commander towards the north-east right before take-off (Credit: via NSIA)

CCTV evidence shows the helicopter lifted off at c 10:35 but crashed less than 20 seconds later, 450 m away, bouncing several times and coming to rest 540 m from the landing site.

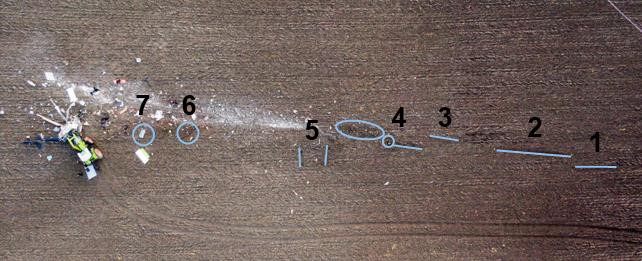

Debris Trail of Wreckage of Midtnorsk Helikopterservice Airbus AS350B3 LN-OBP: The numbers reference the text description above. The tractor that was used to free one of the passengers is seen in the picture. A bucket of paint, which was part of the luggage, was destroyed and the paint has left white stains from point (Credit: Trøndelag Police District & NSIA)

The pilot, who suffered several back fractures, regained consciousness, egressed the helicopter and raised the alarm. The Emergency Locator Transmitter [ELT] antenna had factored during the crash and the helicopter tracking system had not registered the short flight.

Dense fog contributed to the problem of locating the aircraft. After 10–15 minutes, a doctor and rescue personnel arrived at the accident site. Both a rescue helicopter and an air ambulance helicopter were unable to land near the accident site due to fog. After a little while, the air ambulance helicopter was able to land in a field slightly higher up in the terrain about 2 km from the accident site.

Wreckage of Midtnorsk Helikopterservice Airbus AS350B3 LN-OBP (Credit: NSIA)

NSIA Safety Investigation & Analysis

There are no indications of any pre-impact technical failures. NSIA concluded the helicopter was most likely overloaded by c 60-80 kg.

A key issue for the NSIA has been to evaluate why the commander made the decision to lift off.

Investigation & Analysis – Weather and the Decision to Take Off

Apart from the passengers the pilot was the only other person at the base when he was preparing for the flight.

The pilot had earlier driven around the area and stated that the fog…

…varied in density and coverage throughout the morning. When he took off, it was sunny and the sky was blue right above the helipad.

Blue Sky Above the Hangar at 10:19 (Credit: via NSIA)

He has explained that there was still some fog around the helipad, but that it was clear towards the north / north-east where there was good enough visibility

A motorist who passed the accident site shortly after said ” the fog suddenly became very dense right beside the accident site, and that they had to reduce their speed as visibility was only 30 m”.

A roofer working on a house in the nearby villages of Forbregd / Lein took a video of the weather conditions at 10:22.

Local Weather: Mosaic of still images from a video taken in Forbregd Lein at 10:22 (Credit: via NSIA)

The altitude of the houses and the fog are about 130 m above mean sea level (MSL). The helicopter company base is located behind the hill, just left of the centre of the image, and about 100 m lower. Fog can be seen on both sides of the hill.

At Verdal, which is in Class G airspace, the Standardised European Rules of the Air (SERA) allowed horizontal visibility down to 1,500 m, but the flight would still needed to be conducted clear of clouds and with visibility to the ground. If LN-OBP had still been equipped with an attitude indicator, operations could be performed in 800 m visibility.

Fog is a dynamic phenomenon that can change density and extent in a very short time span.

It is also very difficult to determine distance in fog, and humans rely on sharp contrast to be able to do so. Fog erodes this contrast, which can make determining distance very difficult. Visibility in fog can also vary a lot both in a horizontal and vertical direction, which means the sky can be blue above while the aircraft is enclosed in fog.

The NSIA does not rule out that the commander may have had a window in the fog that allowed take-off, but that it may have closed in again in the minutes after the decision to take off had been made.

The flight lasted between 10 and 20 seconds from take-off to the accident. Based on all available information the NSIA considers it probable that the commander lost all visual references almost immediately after taking off.

It is most likely that the horizontal visibility was not adequate, such that the references were lost when the pilot started flying forwards. The sun was at this time in the south-east. This means that the pilot could have faced the sun, which would make the situation worse. The sun would light up the fog and make the contours less pronounced.

Based on the commander’s explanation, the NSIA believes that he was startled by the situation and therefore acted on pure instinct when he lost his visual references. It is then natural to descend to regain visual references, but the fog was probably so dense that this did not occur until it was too late.

NSIA say the following factors may have contributed to the decision to take off in the prevailing conditions:

- Drift: The NSIA found that the company’s operational control was “deficient” and opined “there is

therefore an increased probability that the reference point for safe operation may have shifted such that the safety margins were reduced”. They reference Scott Snook‘s masterpiece ‘Friendly Fire‘ and the concept of practical drift. - A wish to please the customer: The passengers were repeat customers and the tasking had already been cancelled and reschedule twice due to weather.

- The next mission: The pilot had another task waiting, and so “he may have felt a certain pressure to take off as time went on, without necessarily being aware of this”.

- Other pilots who had taken off: The flight was from the pilot’s home base and the two others pilots departing earlier may have encouraged a decision to depart.

- Changing weather conditions: The changing weather may have created an expectation that the fog was about to clear. “The challenge is that it is often impossible to know how long a window will last, and it is therefore challenging to know whether the necessary safety margins of the operation are still met”.

- Alone as decision-maker: The pilot was alone when evaluating the situation and had nobody to discuss it with.

Investigation & Analysis – Survivability & Harness Production Quality

NSIA estimated that the helicopter hit the ground at a relatively shallow angle with the left skid at a speed of 70–100 kt. The NSIA believe the impact sequence was as follows:

The left skid hit a large rock right under the surface 35 m after the first contact. The helicopter tilted forward and the nose impacted the ground. The helicopter then began a clockwise rotation about the vertical axis and an anti-clockwise rotation about the longitudinal axis. The helicopter bounced upwards and continued for about 25 m before it again impacted the ground with its left side before again impacting the ground hard after another 8 m ground on its left side. The helicopter then bounced a final 10 m. At the very end of the accident sequence, the helicopter stood upside down on the rotor head before it fell on to its left side and stopped moving.

Despite the dynamics of the impact:

Since both the commander and the dog survived, the NSIA considers the accident to be survivable

The passengers were both seated to the left hand side if the fuselage. The front passenger died due to “major injures to the head, chest and abdomen”. Their harness was “placed too high up on the stomach and not down towards the hips”. This has been noted on other accident reports. It can occur when the shoulder straps are fitted before the lap strap is adjusted. In 2019 Aerossurance discovered a certain North American company marketing passenger briefing videos with CGI that that misleadingly showed the harness being tightened without the body of the passenger in shot, thus giving the false impression that a high buckle was appropriate.

Furthermore “the rotary buckle failed so that the right-hand shoulder and lap strap become undone during the accident and the passenger was thrown from the helicopter”.

Investigation showed 3 of the 4 screws within the rotary buckle had suffered from hydrogen embrittlement. The manufacturer of the buckle, Parker-Meggitt had become aware of a batch of defective screws in June 2012 “when a customer returned a rotary buckle with fractured screws”.

Until the accident involving LN-OBP, Parker-Meggitt had identified the earliest production date of defect rotary buckles as 27 March 2012, and was certain that no defect rotary buckles had ended up in an aircraft.

However, the passenger seat rotary buckle was produced on 5 March 2012, suggesting an earlier origin of the defect. In 2013 the screw material was changed to stainless steel to avoid any future hydrogen embrittlement problems.

The rear passenger seat only had a three-point harness, but the shoulder strap had not been used. The rear passenger’s torso ended up partly outside the helicopter, crushed under the wreckage. They died due to “fractured neck vertebrae and major internal crush injuries”. The unrestrained cargo may have pushed them laterally and contributed to them becoming crushed.

The pilot told investigators…

…he had only told the passengers to remember to use the safety belts, as they had flown on numerous occasions previously. How they used them was not checked.

Investigation & Analysis – Management of the Air Operator & Safety Management System (SMS)

The NSIA has previously highlighted the challenges related to the organisation and distribution of roles in small operators, namely:

- Cessna 560 Citation Encore LN-IDB 11 January 2017 (2020/03); where the Accountable Manager

also held the positions of Safety Manager and Compliance Monitoring Manager - AS350B3 LN-OVO 27 April 2013 (2014/06) where the pilot failed a breathalyser test (which we have previously discussed).

- BAe Jetstream 31 SE-LGA 30 November 2001 (2005/11); a company “characterised by marginal organisational resources”, where the Accountable Manager, was also Flight Operations Manager, Training Manager and a line pilot. while the Technical and Quality Mangers were part time.

- Beech King Air 200 LN-TSA 19 March 1993 (1994/03); where the accident aircraft commander was also “a board member, general manager, flight manager, operations manager and instructor”.

The Accountable Manager / accident pilot…

….explained that the administrative part of running the company took up so much time that he no longer felt he got enough flight time.

This is perhaps not surprising with them holding four management positions, including being Safety Manager. NSIA commented that “there was not a lot of formal safety management” in the operator and…

“Proactive safety management from the operational management seem to have been limited or absent.” This meant they were lacking “reflection about the challenges [the] company faces and what can be done to make the operation even safer”. However:

In principle, everyone [interviewed within the operator] has stated that the standard of safety has been good.

The pilot went on to explain:

The financial situation of the inland helicopter segment has also deteriorated over time. The Manager of Flight Operations has stated that there has been strong competition in the inland helicopter segment for as long as he can remember, and that finances have always been a factor.

In response to questions about how day-to-day operations were conducted, both pilots and the Manager of Flight Operations has stated that this was mainly handled by the Accountable Manager and that much was done informally. The Accountable Manager scheduled which pilot was to fly which mission and had an overview of how each mission was to be conducted. The Accountable Manager supported the pilots with respect to planning and performing missions. The Accountable Manager was also the one who was the most present at the base and involved in the flight operational questions.

The investigators concluded that…

…the Manager of Flight Operation’s actual possibility to have operational control of day-to-day operations has been limited.

NSIA acknowledges that few people must occupy many roles in small operators, but it is then important that compensatory measures are implemented so that safety is assured. The distribution of roles is designed to ensure that different roles function as corrections and safety barriers.

When one individual, who is also in a position to bypass the Manager of Flight Operations, holds too many of these roles, the credibility of the safety management system in practice can be questioned. In such cases there is a considerable risk of practical drift.

We would observe that appointing part time Safety & Compliance Manager with no other responsibilities in the operator and having the Accountable Manager be the Manager of Flight Operations in name, rather than just practice, might have been a better arrangement to provide independence and credibility.

Investigation & Analysis – Continuing Airworthiness Management

Investigators discovered that:

- The artificial horizon (Attitude indicator – AI) had been removed from the helicopter without proper

documentation and the gap covered with electrical tape.

- An unapproved centre stowage unit of corrugated aluminium was fitted in the cockpit. It was secured using three of the cargo rings, making securing cargo more difficult.

- An unsecured fibreboard floor protector was fitted to the rear cabin which “interfered with the structure of the rear seats and the energy absorption mechanism of the front seats”.

- The front passenger seat crotch strap was stowed under the seat.

The first two were present during the last Airworthiness Review Certificate (ARC) inspection so should have been detected and was interpreted by NSIA as a sign of insufficient operational control.

Investigation & Analysis – Regulatory Oversight

CAA Norway had only four authorised inspectors for the onshore helicopter industry at the time of the accident. NSIA explain that CAA Norway employs risk-based oversight.

CAA Norway has told the NSIA that it can be challenging to translate the risk profile into an appropriate compliance monitoring audit.

The NSIA questions whether CAA Norway has enough resources to properly handle all its statutory tasks related to the inland helicopter segment.

The NSIA recommends the Ministry of Transport to conduct a study of which resources are required to perform risk based oversight activities of the inland helicopter segment, seen in conjunction with the over representation the segment has in the accident statistics

CAA Norway had however audited this operator annually.

The NSIA has studied the audit reports and observe that the findings mainly address a lack of reporting seen in conjunction with the amounts of flight hours produced, lack of training of personnel, inadequate job instructions, outdated manuals with respect to the regulations, inadequate training plans for standard operating procedures, unclear procedures, inadequate emergency kit and similar findings. There are also several recurring findings, as well as inadequate documentation about the implementation of safety management.

However, there were “no signs that this had led to any significant consequences” for the operator. CAA Norway told NSIA that the organisation and distribution of roles at the air operator had also been discussed during audits as the regulator was “not happy with the organisation” but this was not recorded.

The NSIA is of the opinion that only discussing a problem during an audit without any form of documentation is not an adequate compensatory measure. When this occurs repeatedly, there is a danger of it becoming a mere formality for those involved without it actually increasing awareness of the problem.

Further:

CAA Norway has told the NSIA that they have limited options with respect to the distribution of roles since the regulatory framework allows for one person to hold all the statutory roles. The NSIA disagrees with this. The current regulation contains limitations that have been clarified in the new basic regulation. (EU) 2018/1139 Article 4 second paragraph letter f states “the extent to which the persons affected by the risks involved in the operation are able to assess and exercise control over those risks” shall be considered. Even though (EU) 2018/1139 is not [currently] incorporated in Norwegian law by autumn 2023 the NSIA presumes that the principles of article 4 can be used in CAA Norway’s considerations, ref. AIC-N 02/17.

NSIA’s Conclusions

The NSIA believes that the accident in Verdal on 1 November 2022 occurred due to the loss of visual references shortly after take-off in the transition from vertical to horizontal flight.

Based on the commanders explanation the NSIA believes that he might have been startled by the situation and therefore acted on pure instinct when the visual references were lost. It is then natural to descend to try and regain visual references. Due to the density and extent of the fog, the references were not regained before the accident.

The investigation suggest that the organisation…was not in line with the intention of the regulations. The CAA Norway had approved the company, but its oversight activities had not caught the challenges posed by the company’s organisation. The organisation of the company led to the operational control being deficient. CAA Norway aims to perform risk-based supervision, but has challenges translating the risk profile of a company into a tailored audit.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss – Part 2: Survivability

- Alaskan AS350 CFIT With Unrestrained Cargo in Cabin

- Low Viz Helicopter CFIT Accident, Alaska

- Sheriff Super Puma Brownout Accident: NTSB Report

- BK117 Offshore Medevac CFIT & Survivability Issues

- That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring

- Regulator Missed the Chance to Intervene Before Fatal Tour Accident say TAIC

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident

- Fire-fighting Bell 204B Underwater Escape

- Fatal Mi-8 Loss of Control – Inflight and Water Impact off Svalbard

- Canadian Coast Guard Helicopter Accident: CFIT, Survivability and More

- Korean Kamov Ka-32T Fire-Fighting Water Impact and Underwater Egress Fatal Accident

- NH90 Caribbean Loss of Control – Inflight, Water Impact and Survivability Issues

- FOD and an AS350B3 Accident Landing on a Yacht in Bergen

- Beware Last Minute Changes in Plan

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- Air Ambulance A109S Spatial Disorientation in Night IMC

- A HEMS Helicopter Had a Lucky Escape During a NVIS Approach to its Home Base

- Air Ambulance Helicopter Struck Ground During Go-Around after NVIS Inadvertent IMC Entry

Recent Comments