Fatal Fatigue: US Night Air Ambulance Helicopter Loss of Control – In-flight Accident (Air Methods AS350B2 N127LN, Wisconsin)

On 26 April 2018 Air Methods Corporation (AMC) Airbus Helicopter AS350B2 air ambulance helicopter N127LN was destroyed in a Loss of Control – In-flight (LOC-I) accident near Hazelhurst, Wisconsin. The pilot and two medical personnel aboard were fatally injured. The helicopter, operating as ‘Ascension Spirit Air‘, was on a night repositioning flight after two prior inter-hospital patient transfer flights with a refuelling stop. The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has issued a simple probable cause:

The pilot’s loss of helicopter control as a result of fatigue during cruise flight at night.

Wreckage of Air Methods (AMC) Airbus Helicopters AS350B2 Air Ambulance N127LN near Hazelhurst, WI (Credit: NTSB)

The Final Flights and the Pilot’s Immediate History

The NTSB explain in their safety investigation report (issued 23 September 2020) that…

The accident flight was the [34 year old] pilot’s first flight after a week-long family vacation in Florida. …the pilot had a sleep opportunity of more than 9 hours during each of the 6 nights before the accident. The trip [home the day before]…involved [a flight, a 4 hour drive and] a change in time zones.

AMC pilots work 12-hour shifts, with a 7 days on and 7 days off, then 7 nights on and 7 nights off pattern. In this case the pilot was resuming the roster with a night shift.

The pilot’s wife reported no issues with the pilot falling asleep or staying asleep. The pilot’s wife thought that he went to sleep between about 2100 and 2130. The time that the pilot awoke on the day of the accident was not known. The pilot’s wife stated that, before going on duty, he would normally rest and sleep during the day…

The pilot’s wife had also been an AMC pilot for 10 years and was then a pilot at the same base. She was resuming the roster with a day shift and the implication was she had left home before her husband awoke. Contemporary press reports suggest the family had two young daughters. It is explained that the pilot:

…took the kids to daycare so that he could rest for his night shift. He went to the grocery store in the morning and then went home to rest. At about 4:00PM he took his daughter to a doctor’s appointment.

She saw her husband when he arrived at work for the night shift and thought that he had arrived about 45 minutes early for his shift.

He arrived early because he was already in town for the doctor’s appointment and his wife had turned down the flight to Madison, Wisconsin (see below) for duty time reasons.

They did the shift change together, and she noted nothing unusual about her husband. Cellular telephone records indicated his activity from 0725 to 2057 with three extended breaks in activity (greater than 60 minutes) from 0923 to 1118, 1431 to 1556, and 1741 to 2040.

Of these three periods the first could overlap with the grocery shopping and the third does overlap with flying (see below). Beyond one witness statement and analysis of phone records the NTSB human factors analysis does not reconstruct the pilot’s daytime activities further.

The NTSB explain the helicopter and crew had…

…transported a patient from the Howard Young Medical Center Heliport (60WI), Woodruff, Wisconsin, to the Merrill Municipal Airport (RRL), Merrill, Wisconsin, departing about 1759 and arriving about 1819.

The helicopter then departed from RRL about 1832 with another patient aboard and landed at the UW Hospital and Clinics Heliport (WS27), Madison, Wisconsin, about 1937. The patient was offloaded, and the helicopter departed WS27 about 2028 for refueling at Dane County Regional Airport (MSN), Madison, Wisconsin, arriving about 2037.

The total flight time for the first three flights was 94 minutes and occurred over a period of about 2 ½ hours. About 2104, the pilot radioed the operator to report that the helicopter was ready to depart MSN for 60WI.

According to information from the helicopter’s on-board Appareo Vision 1000 recorder (which records image, audio, and parametric data), the pilot conducted a preflight of the helicopter with the engine operating, and no anomalies were detected.

Noticeably:

Yawning and sighs were heard. The pilot requested clearance to 60WI and departed about 2107. About 1 minute later, the pilot asked if the medical crew was “alright back there,” and one of the medical crewmembers responded “yup.” One of the medical crewmembers then stated, “question is are you alright up there?” The pilot responded, “uhhh think so. Good enough to get us home at least.”

About 2200, a medical crewmember stated, “I could go to sleep,” and the pilot responded, “yeah that’d be nice huh.”

This was followed by a couple of radio calls then:

After about 2215, the medical crewmembers started non-aviation-related conversations [mostly about hunting], and the pilot was last heard during the conversations about 2229.

Between about 2215 and 2242, the pilot made movements including raising his left arm near his helmet (which was mounted with night vision goggles), flexing his legs, adjusting his seating position, and changing cyclic position.

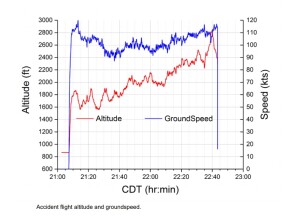

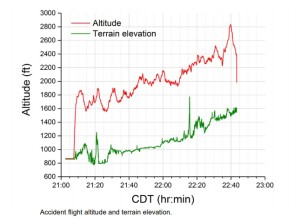

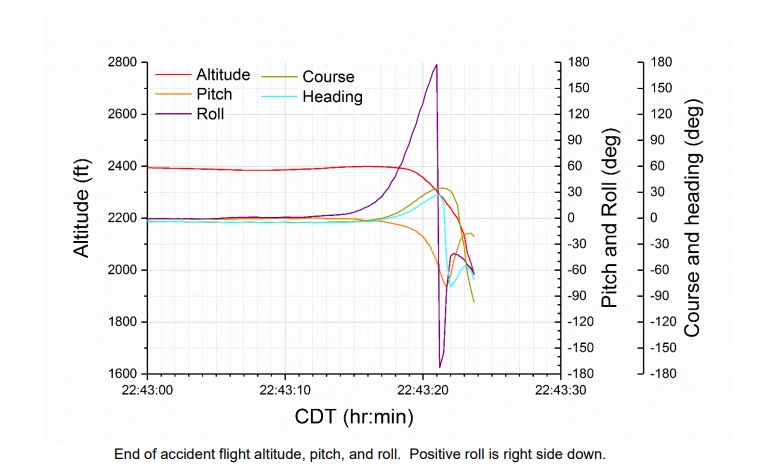

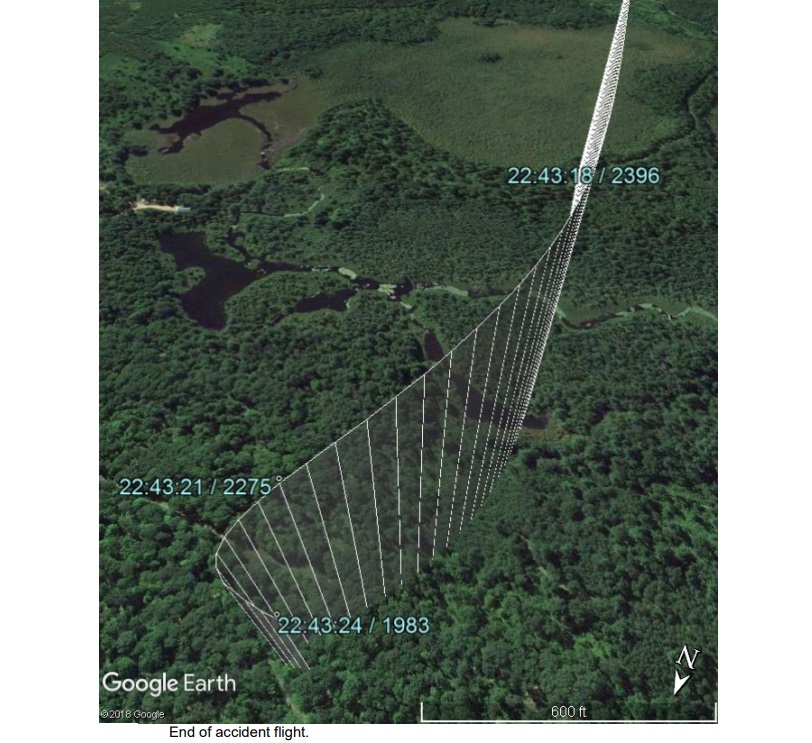

About 2243, the helicopter was operating in level flight at an airspeed of 126 knots and an altitude of at 2,280 ft mean sea level (msl).

The artificial horizon indicator then showed the initiation of a right bank. The pilot’s right forearm started moving along with the cyclic to the right, and the artificial horizon indicated a bank between 10° and 15°. The roll rate to the right appeared to increase rapidly, and the pilot’s body, right forearm, and right hand (which was holding the base of the cyclic grip) appeared to move along with the increased roll rate.

A medical crewmember stated “what are we doin’?” twice. The pilot’s head moved to the right and could no longer be seen in the image, and the right bank increased to more than 90°.

A medical crewmember stated, in a strained voice, “Ohhh [expletive].” The crewmember then shouted “what?” and the pilot’s name. The other medical crewmember also shouted the pilot’s name.

The pilot’s head returned to the image and moved to the left. His right hand still gripped the cyclic. The artificial horizon showed an inverted indication, and the torque gauge indicated a value beyond the red line. The emergency locator transmitter light illuminated while the pilot’s head and upper body moved to the left. Sounds similar to a rotor high rpm horn and a grunt were recorded, along with a medical crewmember shouting the pilot’s name. The recording contained no response from the pilot when the crewmembers shouted his name.

The artificial horizon indicated a right roll of more than 270° with a pitch-down attitude, the altimeter indicated 1,900 ft msl, and the airspeed indicator showed 98 knots. The last two frames showed that the pilot’s head and upper body had moved to the right and that the airspeed indicator displayed 70 knots, the artificial horizon indicated a 90° left bank with a pitch-down attitude, and the altimeter indicated 1,825 ft msl.

The helicopter wreckage was found 3.5 hours later.

Wreckage of Air Methods (AMC) Airbus Helicopters AS350B2 Air Ambulance N127LN near Hazelhurst, WI (Credit: NTSB)

No adverse medical history or toxicology findings were recorded in the brief medical factual report.

Air Methods Procedures, Safety Management, Reporting of Fatigue and Pre-Flight Risk Assessment

The NTSB Human Factors Factual Report contains a description of the Air Methods’ voluntary Safety Management System (SMS), fatigue related procedures and fatigue safety promotion material. The company Operations Manual stated that:

Pilots will report for duty with the appropriate rest and be capable of performing their assigned flight crewmember duties. At any time a flight crewmember becomes medically or physically unfit for duty they shall vocally notify the appropriate aviation manager, self-ground and comply with the requirements of CFR 61.53.

61.53 is strictly the requirement for “prohibition on operations during medical deficiency” rather than a specific fatigue regulation.

However, there is no mention in the NTSB Human Factors Factual Report of whether Air Methods, a company with over 450 aircraft and flying 150,000 hours per annum, had ever recorded any fatigue related reports in their SMS. In an appended interview the pilot’s wife stated that in her experience flying for AMC:

Pilots could call a “time out” if they were exhausted. Their current base was a slower base and they did less time outs than when at their previous base. There were no repercussions if a pilot called in fatigued. She could not remember if her husband had ever called a “time out” but she was sure at some point over a 10-year career that he had. Pilots were never pressured to take a flight when they were tired or fatigued, or if there was marginal or questionable weather.

Neither she nor her husband had concerns about working the night shift; it was only 7 nights a month. She thought a pilot would call a time out before they felt tired in flight. Her husband never mentioned falling asleep or difficulty staying awake when flying. There was no guidance from Air Methods about what to do if a pilot became tired during a flight.

The local AMC manager (a former H145 pilot) commented in interview that:

What shift a pilot worked was not necessarily related to vacations. A pilot might have to work harder to transition back to a night shift after being on vacation. There was no specific guidance as to how to handle off duty time outside the requirement that a pilot could not be scheduled for duty when they were off duty. It was the pilot’s responsibility to show up rested for their shift.

There were no repercussions if a pilot was fatigued. The pilot would be told to go home and get rest and let the company know when they could return. He had never called in fatigued personally but he was aware of a few instances where a pilot had done that. They were so few and far between he could not recall a story about a pilot calling in fatigued.

If a pilot was fatigued during a flight, he would call the aviation manager, let them know where he was, that the flight was finished, and he felt tired. The company would make arrangements to stay the night and get another pilot to relocate the aircraft. He never had a conversation with a pilot about fatigue midshift, only if there was a delay that would extend the pilot’s duty day.

There was no real guidance from the company about fatigue but there was a bed in the office if a pilot felt tired or the pilot should step up and say something and stop that flight from coming forward.

Asked if a pilot feeling fatigued in flight or nodding off would be considered a reportable event, he thought it could be [our emphasis added].

Remarkably, at the time of the interview (September 2019 – 17 months after the accident) he stated:

The company had not put out any information since the accident related to fitness for duty. Pilots at the company had heard that the investigation had moved towards human factors, but nothing was being discussed because it was speculation.

In contrast and unremarked by NTSB, during one of that evening’s flights the medical personnel stated:

19:03:52.2 MC2: what annoys the # [redacted] outta me about that is ya have the fricken’ right to give yourself a rest period. You can say ‘I’m not takin’ anything for X amount of hours – don’t call me.’

19:04:05.7 MC1: everybody’s afraid to pull the trigger on that.

19:04:23.0 MC1: the funniest thing I find – in all the training we do – especially with Air Methods – it’s – ya don’t feel fit to fly – ya don’t fly. so if ya call yourself off from flying – after calling in four times here – they start penalizing you by writing you up. Five is a written – six is a possible suspension – seven’s definitely a suspension – eight you’re terminated within a rolling twelve month period.

19:04:11.5 MC2: got ya

19:04:12.0 MC1: and a doctor’s note does not even count. you gotta apply for family medical leave and get it cleared that way to have it taken off – that’s the only way – otherwise that’s how it sits.

19:04:21.0 MC2: that’s stupid.

19:04:21.7 MC1: so tell me if I don’t feel good enough to fly – how I’m supposed to keep me safe and everybody else safe when you’re gunna penalize me for it.

The pilot made no comment during this conversation.

In accordance with 14 CFR 135.617 Air Methods has a Pre-Flight Risk Analysis (PFRA) Program. Its intent was stated as “to assist in reducing incidents and accidents” and “to assist pilots in identifying, assessing, managing risks and ensuring they are mitigated, accepted or declined”. Their iPad PFRA Tool was “designed to provide the Pilot and the OCC with a robust method of assessing the risk for each flight.”

Information (risks) inputted to the PFRA by the pilot related to (1) pilot and crewmember, such as pilot experience as single pilot, at current base/program, and using night vision goggles; (2) aircraft, such as MELs and aircraft weight within 200 lbs of max HOGE; and (3) flight request, such as if crew had flown more than 3 flights during the shift, weather and turbulence, flight taking place between 0100 and 0500, planned completion time of flight will take more than 4 hours and planned completion time of flight past 12th hour of duty day. Each risk was weighted and factored into the overall score…

The local AMC manager commented that:

He did not think there was anything in the preflight risk assessment that consider a flight for a pilot that was coming on shift after being on vacation but there was consideration given if a pilot had been on shift for several days in a row; he thought that would move them up to the next level. There was consideration given if a pilot had been off duty for 60 days or more.

PFRAs are sent to the company Operational Control Centre (OCC) in Englewood, Colorado for verification, a check of relevant weather data and approval/rejection before the flight commences.

The OCC may request a call with the pilot prior to their decision.

The PFRA for the accident flight had a total score of 6 (low risk) and received an “Approved-OCC” response at 1727 on April 26, 2018.

The NTSB do not comment on either the effectiveness or indeed the potential unintended consequences of a tool that gives a low risk score to a flight that suffered a fatal accident. Nor do they comment that the approval was prior to the first of multiple sectors to conduct two tasks and was given 5.25 hours before the accident occurred. Similar issues were observed in this case study: HEMS A109S Night Loss of Control Inflight

Our Observations

Fatigue is often difficult to determine in fatal accidents. In this case the pilot was adjusting to a night shift after a week of leave. The evidence suggests the pilot most likely had adequate rest the night before, did have opportunity at least to rest during the daytime and had undertaken some relatively standard taskings prior to the accident. Here the presence of a recording system provided some evidence from recorded crew statements and this, and the absence of any medical data that might have otherwise indicated a pilot incapacitation, appears to have been sufficient for the NTSB probable cause determination.

It is however disappointing that none of the established scientific tools for assessing fatigue risk were not used during the investigation. For example the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) in their report into an Airbus A319 that lost both engine fan cowlings used a Health and Safety Executive (HSE) 2006 fatigue and risk index tool to model the likely fatigue of the maintenance personnel involved.

While the pair of interviews recorded presented suggests that pilots could and did turn down flights when they felt fatigued without any adverse consequences and that fatigue was actually rare, it does not appear that NTSB examined actual safety reports to verify what data the operator’s SMS had gathered on fatigue concerns.

It is startling that 17 months after the accident there was reportedly no specific extra emphasis on fitness for duty within the operator. Nor are any safety actions reported by NTSB or recommendations made. After a non-fatal fixed wing night air ambulance accident (Fatigue Featured in Anchorage Alaska Air Ambulance Accident) the pilot sensibly discussed the idea of a pre-flight personal wellness check.

Not for the first time a pre-flight risk assessment score card proved useless in even highlighting an accident flight as being an elevated risk. These scoring systems are typically uncalibrated and their effectiveness is rarely monitored, while giving the illusion of managing risk.

One might also wonder if hospitals are unnecessarily requesting patient transfers after dark.

Wreckage of Air Methods (AMC) Airbus Helicopters AS350B2 Air Ambulance N127LN near Hazelhurst, WI (Credit: NTSB)

Safety Resources

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- HEMS Black Hole Accident: “Organisational, Regulatory and Oversight Deficiencies”

- Life Flight 6 – US HEMS Post Accident Review

- More US Night HEMS Accidents

- US HEMS “Delays & Oversight Challenges” – IG Report

- Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident

- HEMS S-76C Night Approach LOC-I Incident

- US HEMS Accident Rates 2006-2015

- Fatigue Featured in Anchorage Alaska Air Ambulance Accident

- Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- Taiwan NASC UH-60M Night Medevac Helicopter Take Off Accident

- HEMS A109S Night Loss of Control Inflight

- HEMS AW109S Collided With Radio Mast During Night Flight

- Ambulance / Air Ambulance Collision

- Hanging on the Telephone… HEMS Wirestrike

- Air Ambulance Helicopter Fell From Kathmandu Hospital Helipad (Video)

- NTSB Investigation into AW139 Bahamas Night Take Off Accident

- Night Offshore Training AS365N3 Accident in India

- Norwegian HEMS Landing Wirestrike

- Fatigued Flight Test Crew Superjet 100 Crosswind Accident

- Embraer ERJ 170 FMS Error & Fatigue

- Perception and Fatigue: CH124 Sea King Engine Failure

- Maintenance Personnel Fatigue and Alertness

- A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Report

- That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring

- The Tender Trap: SAR and Medevac Contract Design Advice from Aerossurance on getting contracts right.

- UPDATE 23 January 2021: US Air Ambulance Near Miss with Zip Wire and High ROD Impact at High Density Altitude

- UPDATE 13 March 2021: S-76A++ Rotor Brake Fire

- UPDATE 17 July 2021: Sécurité Civile EC145 Mountain Rescue Main Rotor Blade Strike Leads to Tail Strike

- UPDATE 31 July 2021: Low Recce of HEMS Landing Site Skipped – Rotor Blade Strikes Cable Cutter at Small, Sloped Site

- UPDATE 21 August 2021: Air Methods AS350B3 Night CFIT in Snow

- UPDATE 19 September 2021: A HEMS Helicopter Had a Lucky Escape During a NVIS Approach to its Home Base

- UPDATE 15 January 2022: Air Ambulance Helicopter Struck Ground During Go-Around after NVIS Inadvertent IMC Entry

Aerossurance customers contract 16 HEMS helicopters of 5 types on-standby in 4 nations.

The Tender Trap: SAR and Medevac Contract Design Aerossurance’s Andy Evans discusses how to set up clear and robust contracts for effective contracted HEMS operations.

The Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) has recently published An Aviation Professional’s Guide to Wellbeing.

This has been written based on the ‘BioPsychoSocial Model of Health’:

Recent Comments