HEMS Black Hole Accident: “Organisational, Regulatory and Oversight Deficiencies”

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) has issued their report into a fatal night-time Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident during a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) departure in ‘black-hole’ conditions. These conditions “typically occur over water or over dark, featureless terrain where the only visual stimuli are lights located on and/or near the airport or landing zone”.

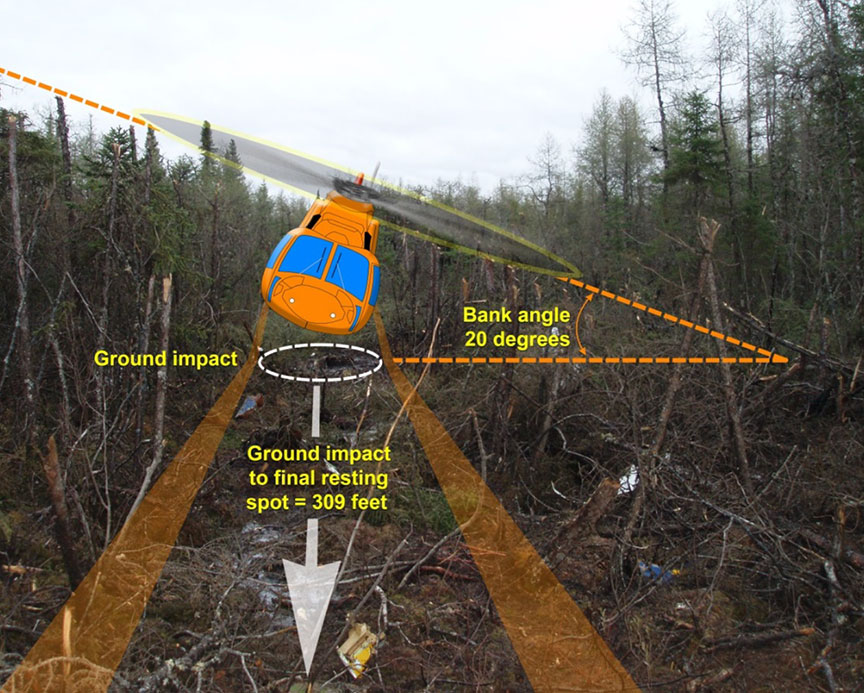

Depiction of Ornge S-76A C-GIMY’s Descent (Credit: TSB)

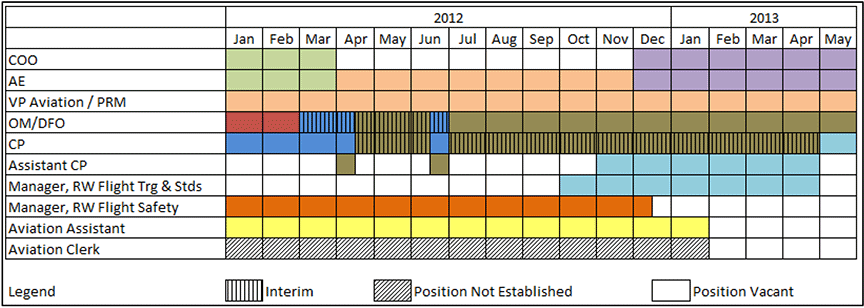

On 31 May 2013, at 0011 Local Time, Sikorsky S-76A helicopter C-GIMY, operated by the rotary wing (RW) arm of HEMS provider Ornge, departed from the remote Moosonee Airport in Northern Ontario.

As the helicopter climbed through 300 feet into darkness, the first officer commenced a left-hand turn and the crew began carrying out post-takeoff checks.

Approximate Flight Path of Ornge S-76A C-GIMY (Credit: TSB)

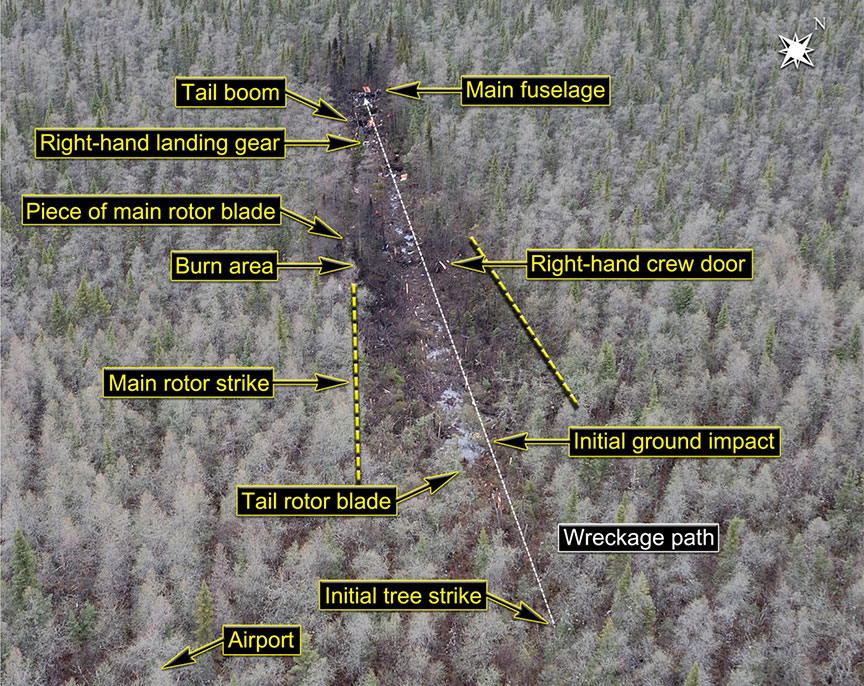

During the turn, the aircraft’s angle of bank increased, and an inadvertent descent developed. The pilots recognized the excessive bank and that the aircraft was descending; however, this occurred too late, and at an altitude from which it was impossible to recover. A total of 23 seconds had elapsed from the start of the turn until impact, approximately one nautical mile from the airport.

Depiction of C-GIMY’s Descent (Credit: TSB)

The aircraft was destroyed by impact forces and the ensuing post-crash fire. All four on board—the captain, first officer and two paramedics—were killed.

Overhead View of the Debris Trail: 405 feet, 318° Track (Credit: TSB)

There was a post crash fire. The helicopter did not have Terrain Avoidance and Warning System (TAWS).

On release of the report on 15 June 2016, Kathy Fox, TSB Chair said:

This accident goes beyond the actions of a single flight crew. Ornge RW did not have sufficient, experienced resources in place to effectively manage safety. Further, Transport Canada (TC) inspections identified numerous concerns about the operator, but its oversight approach did not bring Ornge RW back into compliance in a timely manner. The tragic outcome was that an experienced flight crew was not operationally ready to face the challenging conditions on the night of the flight.

TSB go on:

The investigation uncovered several issues. The night visual flight rules regulations do not clearly define “visual reference to the surface”, while instrument flight currency requirements do not ensure that pilots can maintain their instrument flying proficiency. At Ornge RW, training, standard operating procedures, supervision and staffing in key safety/supervisory positions did not ensure that the crew was ready to conduct the challenging flight into an area of total darkness. The training and guidance provided to TC inspectors led to inconsistent and ineffective surveillance of Ornge RW, as inspectors did not have the tools needed to bring a willing but struggling operator back into compliance in a timely manner, allowing unsafe practices to persist.

The Operator

Ornge (the former Ontario Air Ambulance Corporation renamed in 2006):

…is a not-for-profit company responsible for the provision of air medical transport to the population of Ontario. To carry out its mandate, Ornge created 2 for-profit corporate entities to oversee the fixed-wing and rotor-wing aspects of the company’s EMS mandate.

They had previously contracted air support but gained a fixed wing AOC in 2009 and a rotary wing AOC 6 January 2012. The company had planned to deploy AW139s in early 2012 to all their HEMS bases, with the exception of Moosonee, which they planned to contract out.

However, implementation was delayed due to logistical issues with the AW139’s full ice-protection system, tail-rotor blade airworthiness inspections, and serviceability rates. [and] …the company then elected to delay the deployment of the AW139s in Kenora and Thunder Bay, and to continue using the S-76As that had been acquired by Ornge Global Air Inc. from the previous operator….

The company also abandoned its effort to contract out the Moosonee helicopter “opting to maintain the status quo using the S-76A that was originally stationed there”.

Since the decision to delay the AW139 implementation was intended to be a temporary measure…the company did not complete any type of risk assessment to determine which bases would benefit most from use of the AW139 versus the S-76. According to the company, transition to the AW139 had already begun at the southern bases, and moving the AW139s to the northern bases would have entailed a considerable amount of additional training.

Ornge did not conduct any type of risk assessment to determine whether or not risk levels could be reduced either by reintegrating some of the retired S-76A airframes back into service or by using those retired aircraft as a means to upgrade the in-service airframes that lacked the more modern components [sic – we believe the TSB mean the less well equipped S-76As].

They note there were other changes afoot:

In 2012, Ornge underwent significant organizational change. In January 2012, the previous board of directors resigned, a new volunteer board was appointed, and an interim chief executive officer (CEO) was appointed.

An investigation by the Auditor General into business practices of the former management followed, as did a parliamentary inquiry.

TSB go on:

From January to July 2012, a transition team was put in place to establish a new direction for the organization. In December 2012, a permanent President/CEO was appointed, and he assumed duties on 21 January 2013.

At the time of the occurrence, the majority of the senior management team of Ornge FW and Ornge RW came from a predominately fixed-wing background.

There was a widespread perception among Ornge RW employees that the senior management at Ornge did not have a full appreciation of the challenges associated with running a HEMS operation, due to their lack of rotor-wing experience.

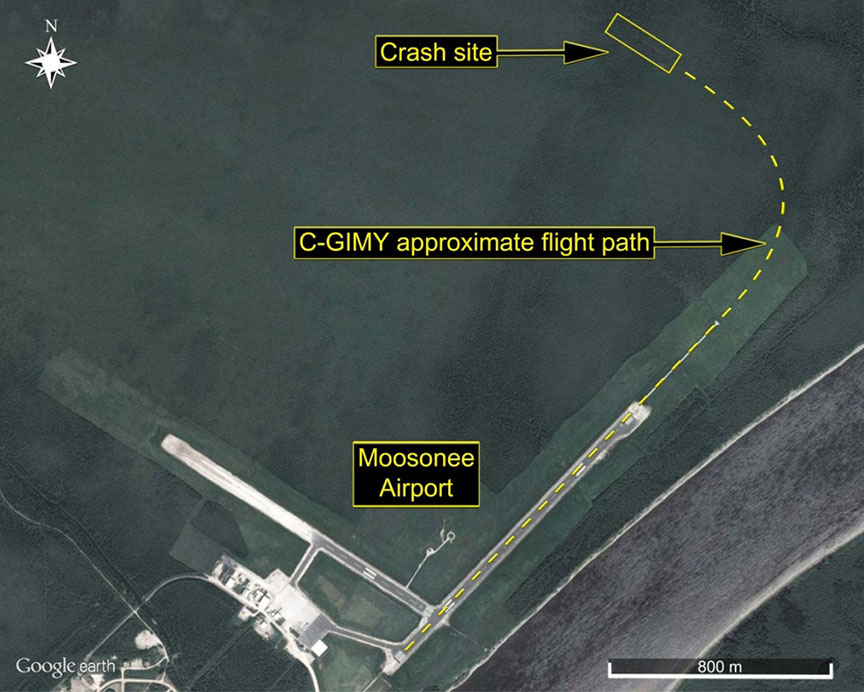

The RW company had a relatively high proportion of staff changes and un-filled posts in the year and half before the accident:

Timeline of Staff Changes at Ornge RW (Credit: TSB)

TSB go on that in this case they:

…found a company that was willing to address safety issues in its operation, but did not have the capacity to effectively do so. TC’s approach to returning the operator to compliance was not matched by the operator’s capabilities.

Training

Although the crew of the occurrence flight were both experienced pilots, both had minimal night flying and instrument flying experience.

Ornge’s training:

…included weaknesses that reduced its capacity to meet the operational needs of Ornge RW crews. For example:

The company’s CFIT-avoidance training program was not specific to each aircraft type. Rather, it provided generic guidance that was, at times, not applicable to the S-76A fleet.

Very little dedicated night VFR training was included in the S-76 simulator training, and little guidance was provided to instructors on how the required night VFR sequences that were included should be presented. As a result, there was little realistic training in night VFR operations.

Crew resource management (CRM) training provided by the company was mostly awareness-based and provided few practical strategies that could be employed by pilots. Moreover, 2 different courses were being taught to company pilots.

Weaknesses were exacerbated by ineffective or inconsistent delivery:

…instances were identified in which pilots (including the pilots involved in the accident) were provided with little time and no company publications to prepare for initial or recurrent simulator training. Once on site, pilots still lacked access to company publications and, in many cases, the training—including black-hole training—was not conducted in accordance with Ornge RW’s SOPs and the Training Manual.

…some of the training required by the company training manual was not included in the simulator training provided by the contractors. Among the training components that were consistently not delivered were practical CFIT-avoidance training and black-hole training… In the case of the crew of the occurrence flight, the captain had received no black-hole training during his recurrent S-76 course because he had declined the training on the basis that it was not realistic. There is no record on Ornge RW training record forms indicating that he received practical CFIT-avoidance training.

…there was little or no follow-up to ensure ongoing skills development and retention. …line indoctrination training was not required, and area familiarization training consisted of a verbal briefing delivered by another company line captain.

Furthermore, the company had no process in place to follow up on problems identified during company training, nor was such a process required by regulation.

Regulatory Oversight by Transport Canada

…systemic training deficiencies were repeatedly identified, first by the company in May 2012, then during TC surveillance activities in December 2012 and January 2013. Each time, TC received assurances that the issues would be addressed.

However, more than a year had elapsed since this issue was first identified by Orgne at the time if the accident. In a TC audit after the accident outstanding issues were identified with:

- practical CFIT-avoidance training;

- lack of sufficient operational management and support personnel to ensure COM requirements were being followed; and

- documentation of the progression of first officers and direct-entry captains.

…the TSB found that TC’s approach to surveillance activities did not lead to the timely rectification of non-conformances. It also found that TC inspectors believed that tools other than a corrective action plan to guide the operator back into compliance were either unavailable or inappropriate for use with a willing operator.

As a result, the operator’s willingness to address surveillance findings superseded concerns about the operator’s capability to address the deficiencies in post-surveillance decision making.

In addition, the investigation found that the training and guidance that was provided to TC inspectors contributed to uncertainty, which led to inconsistent and ineffective surveillance of Ornge.

Ultimately, although TC was conducting frequent and detailed surveillance, the approach to returning the operator to a state of compliance was not well matched to the capabilities of the operator.

TSB Findings as to Causes and Contributing Factors

- The crew conducted a flight under night visual flight rules regulations without sufficient ambient or cultural lighting needed to maintain visual reference to the surface.

- When the pilot flying encountered a lack of visual cues off the departure end of Runway 06, necessitating transition to flight by reference to instruments, an excessive bank angle and rate of descent developed, which were not recognized by the crew at an altitude that permitted recovery.

- The severity of the impact forces caused the deaths of the first officer and one of the flight paramedics, and likely rendered the captain and the other flight paramedic unconscious. The latter 2 individuals likely succumbed rapidly to their injuries before significant inhalation of fire combustion products.

- The crew were not operationally ready to safely conduct a night visual flight rules departure that brought the flight into an area of total darkness.

- Insufficient and inadequate training contributed to the difficulties that the crew encountered during the departure from Runway 06 at Moosonee Airport (CYMO).

- Ornge Rotor-Wing did not have dedicated night-flight standard operating procedures (SOPs) to address the hazards specific to night operations, except for designated black-hole locations, which did not apply to Moosonee. As a result, the inadequacy of the company’s night-flight SOPs contributed to the accident.

- Ornge Rotor-Wing was not using the company’s currency tracking program (i.e., AvAIO) as intended to ensure that pilots were qualified in accordance with both company and regulatory night-flight currency requirements. As a result, the central scheduling department did not identify that, according to inaccurate data in AvAIO, the first officer was not qualified for the flight.

- Although Ornge Rotor-Wing had established policies and procedures defining the operational readiness of its pilots, these were bypassed and eroded by the company, which resulted in the crew not being operationally prepared for the conditions encountered on the night of the occurrence.

- Ornge Rotor-Wing was operating with insufficient and inexperienced personnel in key positions, which allowed unsafe conditions to persist.

- Transport Canada’s approach to surveillance activities did not lead to the timely rectification of non-conformances that were identified, allowing unsafe practices to continue.

- The selection of the corrective action plan process as the sole means of returning Ornge Rotor-Wing to a state of compliance resulted from the belief that other options were either unavailable or inappropriate for use with a willing operator. This belief contributed to non-conformances being allowed to persist.

- The training and guidance that was provided to Transport Canada inspectors resulted in uncertainty, which led to inconsistent and ineffective surveillance of Ornge Rotor-Wing.

TSB Safety Recommendations

The TSB made 14 recommendations to address safety deficiencies in:

- Regulatory oversight

- Flight rules and pilot readiness

- Aircraft equipment

TSB Safety Recommendations: 1) Regulatory Oversight

The TSB note that TC began phasing in regulations for safety management systems (SMS) in 2005:

To date, only the largest operators require SMS, while 90% of Canadian commercial air operators do not require SMS, though a number have been voluntarily implementing it in varying degrees. Even with SMS requirements, companies vary in their commitment and abilities to implement an SMS effectively.

Hence the TSB recommends:

TSB Recommendation A16-12 That the Department of Transport require all commercial aviation operators in Canada to implement a formal safety management system.

TSB Recommendation A16-13 That the Department of Transport conduct regular SMS assessments to evaluate the capability of operators to effectively manage safety.

TSB Recommendation A16-14 That the Department of Transport enhance its oversight policies, procedures and training to ensure the frequency and focus of surveillance, as well as post-surveillance oversight activities, including enforcement, are commensurate with the capability of the operator to effectively manage risk.

TSB Safety Recommendations: 2) Flight Rules and Pilot Readiness

TSB say:

The visual references required for safe night VFR flight are ill-defined. Many pilots believe that it is acceptable to fly at night as long as the reported weather conditions are acceptable, regardless of lighting conditions.

Many night VFR flights safely take place over well-lit, populated areas. However, in remote areas, very little ambient or cultural lighting exists to help pilots maintain visual reference to the ground.

Instrument flying is a perishable skill requiring frequent practice to maintain proficiency. However, instrument-rated pilots can go 12 months after the instrument flight test before being required to do any instrument flying. After that, they must conduct 6 hours of instrument flying and 6 instrument approaches every 6 months. These currency requirements are not sufficient to ensure that instrument-rated pilots are proficient enough to fly safely in challenging instrument flying conditions.

There is currently no requirement for captains to demonstrate a higher degree of proficiency commensurate with their increased responsibilities. In this occurrence, Ornge Rotor-Wing was aware that the captain had encountered problems during the PPC and it was recommended that he fly as first officer to gain experience in the air ambulance environment. However, the company chose to employ the captain as a pilot-in-command without any additional training or supervision.

As seen in this occurrence, there is a risk that pilots will continue to be assigned to captain duties without having first demonstrated a degree of proficiency, commensurate with the responsibilities of the captain of a multi-crew aircraft.

Hence the TSB recommends:

TSB Recommendation A16-08 The Department of Transport amend the regulations to clearly define the visual references (including lighting considerations and/or alternate means) required to reduce the risks associated with night visual flight rules flight.

TSB Recommendation A16-09 The Department of Transport establish instrument currency requirements that ensure instrument flying proficiency is maintained by instrument-rated pilots, who may operate in conditions requiring instrument proficiency.

TSB Recommendation A16-11 The Department of Transport establish pilot proficiency check standards that distinguish between, and assess the competencies required to perform, the differing operational duties and responsibilities of pilot-in-command versus second-in-command.

TSB Safety Recommendations: 3) Aircraft Equipment

TSB say:

Without TAWS, aircraft are at significantly greater risk of controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accidents, such as this one. The TSB has investigated numerous helicopter occurrences that took place at night or in instrument flying conditions where TAWS might have prevented an accident.

Most commercial and some privately-operated fixed-wing aircraft are required to have TAWS, but commercial helicopters are not.

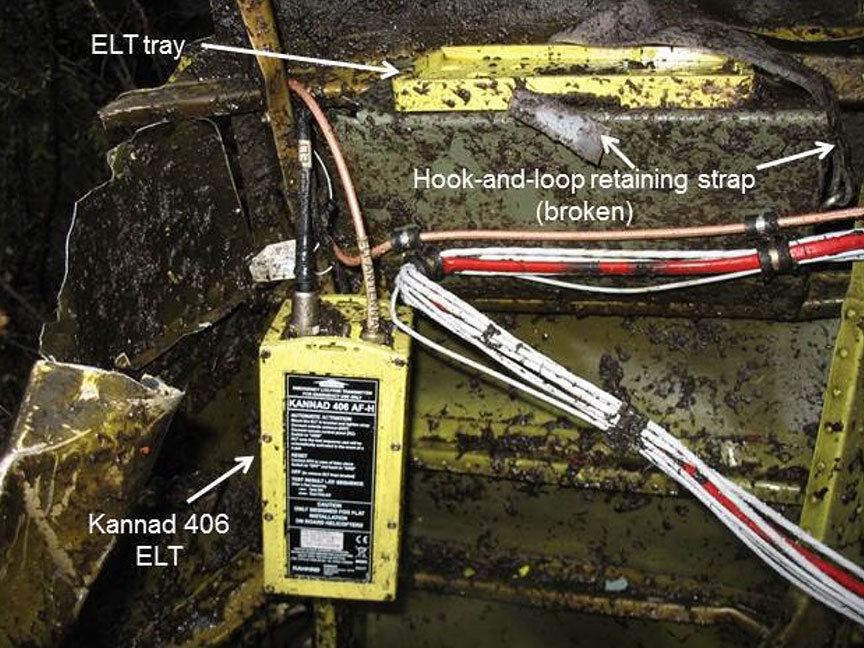

No signal was received from the occurrence helicopter’s ELT. As a result, the Search and Rescue (SAR) crew did not have a precise location of the crash site. While the ELT was not a factor in the accident outcome, the investigation highlighted several factors as to risk related to ELTs.

Canada has no requirement for aircraft to have an ELT capable of transmitting a distress signal at 406 MHz, the frequency monitored by search-and-rescue satellites, as required by International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards… thus exposing people to life-threatening delays in SAR services.

The ELT aboard the occurrence helicopter activated as a result of the crash; however, no signal was received due to a broken antenna. The current design standards are robust for the ELT unit, but significantly less so for the entire ELT system, including such components such as external wiring and the antenna. The TSB has investigated 20 other occurrences where ELTs have been rendered inoperable due to damage sustained during the crash sequence.

The 406 MHz ELTs are required to have a minimum delay of 50 seconds from the time of activation to the first transmission of a distress signal. As such, people may be at increased risk of injury or death following an occurrence in case an ELT is rendered inoperable during the first transmission delay period.

There is a documented history of the ELT type used in the occurrence helicopter coming free from the hook-and-loop fastener intended to secure it. While hook-and-loop fasteners are no longer acceptable in new installations, this requirement is not applicable to previously installed ELTs.

Hence the TSB recommends:

TSB Recommendation A16-10 The Department of Transport require terrain awareness and warning systems for commercial helicopters that operate at night or in instrument meteorological conditions.

TSB Recommendation A16-01 The Department of Transport require all Canadian-registered aircraft and foreign aircraft operating in Canada that require installation of an emergency locator transmitter (ELT) to be equipped with a 406-MHz ELT in accordance with ICAO standards.

TSB recommendations A16-02, A16-03, A16-04, and A16-05 Therefore, the Board recommends to ICAO, the RTCA, the EUROCAE and TC that they… establish rigorous emergency locator transmitter (ELT) system crash survivability standards that reduce the likelihood that an ELT system will be rendered inoperative as a result of impact forces sustained during an aviation occurrence.

TSB Recommendation A16-06 COSPAS-SARSAT amend the 406-megahertz emergency locator transmitter first-burst delay specifications to the lowest possible timeframe to increase the likelihood that a distress signal will be transmitted and received by search-and-rescue agencies following an occurrence.

TSB Recommendation A16-07 The Department of Transport prohibit the use of hook-and-loop fasteners as a means of securing an emergency locator transmitter to an airframe.

The Kannad 406 MHz Automatic Fixed Helicopter (AF-H) Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) Hanging by its Wires Having Broken Free from its Velco(!) Mounting (Credit: TSB)

UPDATE 27 July 2016: A law suit has commenced that alleges that Ornge and Transport Canada “turned a blind eye to safety woes at the air ambulance agency”.

UPDATE 31 October 2016: Ornge is introducing an AW139 to the base.

UPDATE 27 January 2017: A court application is made for access to the CVR by a federal health and safety agency: ORNGE chopper crash investigators want access to cockpit recording

UPDATE 26 April 2017: A court case, brought under Labour Law, commences in Canada. In court the value of night vision systems was discussed: ORNGE urged to give night-vision goggles to pilots before chopper crash, court told. They had been considered for the AW139 but deemed too expensive the court was told. They were allegedly not considered for the older S-76s. The defence try to stress the captain’s responsibility to turn down an unsafe flight (minimising the organisational obligations as part of their defence).

UPDATE 25 April 2018: The lack of night vision goggles was insufficient for Labour Code conviction

…the court considered a due diligence defence. While it held that Ornge fully complied with Transport Canada’s and Orgne’s regulations and requirements for night flying, it agreed with the Crown that “there is an undefined area or space between the regulatory scheme and the [centralised load control] where the general obligation to conduct a safe operation may apply and impose additional obligations”.

The court also considered industry practice and standards, finding that industry recognises that it is impossible to eliminate all risk and that the goal is to reduce and maintain risk at an acceptable level. Further, it was not industry practice in Canada to equip all medical helicopters with night vision goggles. Therefore, Ornge was held not to be negligent in failing to provide night vision goggles for the S76 helicopters…

Other Safety Resources

- The Tender Trap: SAR and Medevac Contract Design Advice from Aerossurance on getting contracts right.

- Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens Devastating rail accidents in the US and Canada highlight the challenges for regulators introducing Safety Management System rules and/or PBR.

- HEMS S-76C Night Approach LOC-I Incident a near accident in Canada

- Life Flight 6 – US HEMS Post Accident Review video and emergency response lessons from a US night accident

- More US Night HEMS Accidents

- Night Offshore Winching CFIT a German HEMS unit attempts night offshore winching

- US Police Helicopter Night CFIT: Is Your Journey Really Necessary?

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- Fatal Helicopter / Crane Collision – London Jan 2013

- Dim, Negative Transfer Double Flameout a New Zealand HEMS BK117 incident with training and experience lessons

- Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident

- US HEMS “Delays & Oversight Challenges” – IG Report

- US HEMS Accident Rates 2006-2015

- R44 Oil & Gas Accident – Alcohol, Flight Following, ELTs more on Velcro ELT mounts

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident TSB raise issues with the TC approach to regulation

- Operator & FAA Shortcomings in Alaskan B1900 Accident NTSB raise issues with the FAA approach to regulation

- UPDATE 19 August 2016: Canadian KA100 Fuel Exhaustion Accident This accident highlights important human factors, competence and regulatory oversight issues.

- UPDATE 11 August 2017: Deadly Combination of Misloading and a Somatogravic Illusion: Alaskan Otter A night departure of a Otter in Alaska into a ‘back hole’ when outside of the weight and CG limits resulted in spatial disorientation, a stall and LOC-I.

- UPDATE 3 September 2017: Night Offshore Training AS365N3 Accident in India

- UPDATE 29 October 2017: How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- UPDATE 15 January 2022: Air Ambulance Helicopter Struck Ground During Go-Around after NVIS Inadvertent IMC Entry

UPDATE 30 December 2016: This was our 5th most popular article in 2016.

UPDATE 22 June 2017: A Canadian Parliament Committee issued a report to the federal government with 17 recommendations, aimed at enhancing aviation safety in Canada. The Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities heard 47 witnesses and received 11 briefs, leading to a report with 17 safety recommendations. These included:

- That the implementation of a Safety Management System becomes mandatory for all commercial operators, including the air taxi sector.

- That Transport Canada:

a. establish targets to ensure more on-site safety inspections versus Safety Management System audits;

b. use poor results from Safety Management System audits (including whistleblower input) as a ‘flag’ for prioritizing on-site inspections;

c. Review whistleblower policies to ensure adequate protection for people who raise safety issues to foster open, transparent and timely disclosure of safety concerns. - That the government make sure that Safety Management Systems are accompanied by an effective, properly financed, adequately staffed system of regulatory oversight: monitoring, surveillance and enforcement supported by sufficient, appropriately trained staff.

- That Transport Canada review all training processes and training materials for civil aviation inspectors to ensure they have the resources to perform their duties effectively.

UPDATE 17 July 2017: TSB CRM/ADM recommendation stemming from 1998 airplane crash ‘still active’

UPDATE 10 November 2017: ORNGE cleared of negligence in Ontario air ambulance crash that killed four

But the judge was highly critical of the regulatory framework within which air ambulance services operate.

UPDATE 7 April 2018: A Shorts 360 N380MQ, operated by SkyWay Enterprises as a Part 135 flight on contract to FedEx crashed in the Caribbean after the crew likely suffered a Somatogravic Illusion raising the flaps on a dark night in 2014. The lack of an FAA SMS regulation for Part 135, the operator’s poor safety culture and implications for the wider industry culture stand out in a thoughtful accident report.

UPDATE 26 May 2018: US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight Four died when Metro Aviation Airbus Helicopter AS350B2 N911GF suffered a loss of control due to spatial disorientation after taking off into night instrument meteorological conditions from a remote site.

UPDATE 10 June 2018: Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident We look at the ANSV report on a HEMS helicopter Inadvertent IMC event that ended with an AW139 colliding with a mountain in poor visibility.

UPDATE 29 September 2018: HEMS A109S Night Loss of Control Inflight

UPDATE 2 November 2019: Taiwan NASC UH-60M Night Medevac Helicopter Take Off Accident

UPDATE 21 December 2019: BK117B2 Air Ambulance Flameout: Fuel Transfer Pumps OFF, Caution Lights Invisible in NVG Modified Cockpit

UPDATE 5 March 2020: HEMS AW109S Collided With Radio Mast During Night Flight

UPDATE 19 April 2020: SAR Helicopter Loss of Control at Night: ATSB Report

UPDATE 23 August 2020: NTSB Investigation into AW139 Bahamas Night Take Off Accident

UPDATE 26 September 2020: Fatal Fatigue: US Night Air Ambulance Helicopter LOC-I Accident

UPDATE 23 January 2021: US Air Ambulance Near Miss with Zip Wire and High ROD Impact at High Density Altitude

UPDATE 31 January 2021: Fatal US Helicopter Air Ambulance Accident: One Engine was Failing but Serviceable Engine Shutdown

UPDATE 17 July 2021: Sécurité Civile EC145 Mountain Rescue Main Rotor Blade Strike Leads to Tail Strike

UPDATE 31 July 2021: Low Recce of HEMS Landing Site Skipped – Rotor Blade Strikes Cable Cutter at Small, Sloped Site

UPDATE 21 August 2021: Air Methods AS350B3 Night CFIT in Snow

UPDATE 19 September 2021: A HEMS Helicopter Had a Lucky Escape During a NVIS Approach to its Home Base

UPDATE 20 November 2021: NVIS Autorotation Training Hard Landing: Changed Albedo

UPDATE 10 June 2023: EC135 Air Ambulance CFIT when Pilot Distracted Correcting Tech Log Error

UPDATE 20 July 2024: Night CHC HEMS BK117 Loss of Control

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. We will be presenting for the second year running. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Recent Comments