C-130J Control Restriction Accident, Jalalabad

The US Air Force (USAF) Air Mobility Command (AMC) has released its accident report into the fatal loss of control (LOC-I) accident involving of Lockheed Martin C-130J 08-3174 during a night-time take-off from Jalalabad Airfield, Afghanistan on 2 October 2015. The accident was caused by the failure to remove a loose article that had been deliberately placed behind the control column during a night-time engines-running turnaround to aid loading.

The Accident

All 11 persons on-board died (four crew, two fly-away security team members of the the 66th Security Forces Squadron and five civilian contractor passengers), as did three Afghan Special Reaction Force (ASRF) personnel as the aircraft struck a guard tower. There was also a post crash fire. This was the worst USAF C-130 accident in the last 25 years.

The aircraft was from the 317th Airlift Group, Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, and operated by the 39th Airlift Squadron, while assigned to the 455th Air Expeditionary Wing at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan.

In an AMC press release they say:

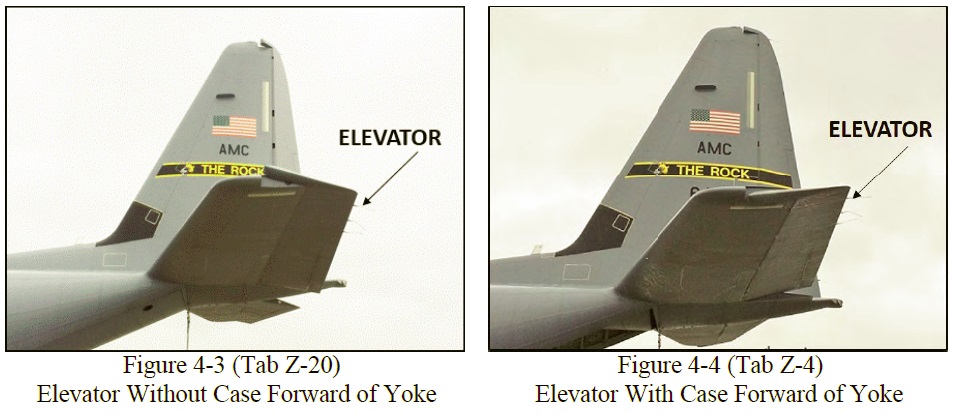

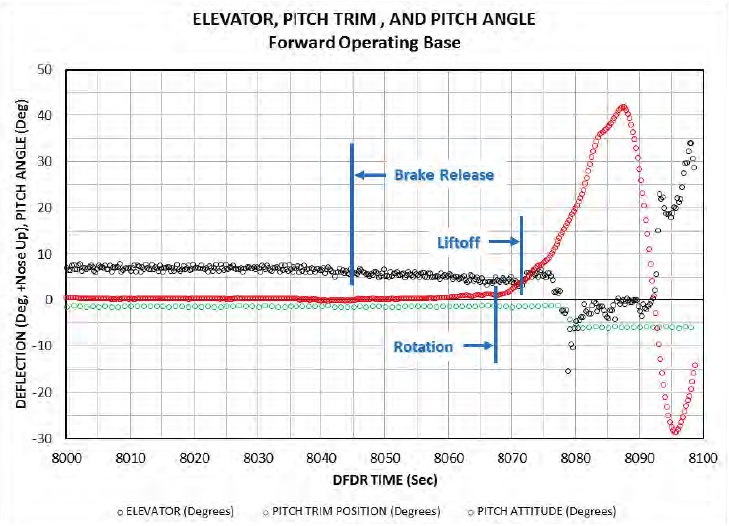

While conducting engine running on-load/offload operations at Jalalabad Airfield, the pilot raised the elevators mounted to the horizontal stabilizer by pulling back on the yoke. This provided additional clearance to assist with offloading tall cargo.

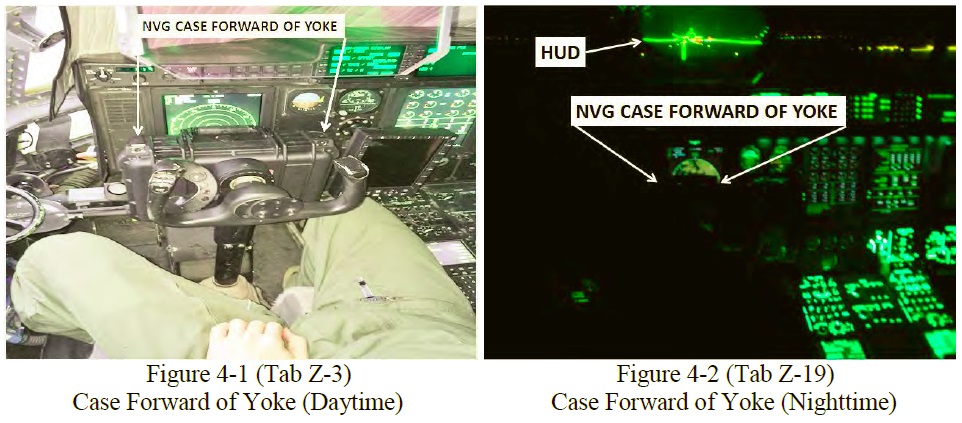

After a period of time in which the pilot held the yoke by hand, he placed a hard-shell night vision goggle (NVG) case in front of the yoke [or control column] to hold the elevator in a raised position.

However, because the pilots were operating in darkened night-time flying conditions and wearing NVGs, neither pilot recognized and removed the NVG case after loading operations were complete or during take-off.

Once airborne, the aircraft increased in an excessive upward pitch during the take-off climb. The co-pilot misidentified the flight control problem as a trim malfunction, resulting in improper recovery techniques. The rapid increase in pitch angle resulted in a stall from which the pilots were unable to recover.

The aircraft impacted approximately 28 seconds after lift-off, right of the runway, within the confines of Jalalabad Airfield.

The investigators say, surprisingly, they could not determine if a flight controls check would have alerted the pilots to the obstruction.

Conclusions

The accident investigation board identified the following causes:

- Inadequate Real-Time Risk Assessment (Hard-Shell NVG Case Placement)

- Distraction

- Wrong Choice of Action During an Operation (Misidentification of Malfunction)

They identified the following contributory factors:

- Environmental Conditions Affecting Vision (i.e. night-time operations, use of NVGs, and reliance on the Head Up Display [HUD] and Advisory, Caution, and Warning System [ACAWS])

- Inaccurate Expectation (in relation to take-off technique applied)

- Fixation (on a trim failure)

Accident Sequence Video and Other Resources

A brief 5s animation of the flight:

AIB Report – C-130J, TN 08-3174 (Report)

AIB Report – C-130J, TN 08-3174 (Tabs A – U)

AIB Report – C-130J, TN 08-3174 (Tabs V – EE)

UPDATE 24 April 2016: The Air Force Times has now covered this accident. They quote sources who observe that such a workaround “was not uncommon”, “there’s no official way to do that other than holding it up by hand” and sometimes items would be used to “prop up yokes”:

It wasn’t sanctioned, it was just something you did. Not always, just sometimes. It’s the end of a long day and you’re tired. Someone wants to stand up and walk around, you’d use something artificial to hold that up.

During an engine running turnaround:

…the pilot and co-pilot may not have performed the full pre-flight check that includes ensuring no flight controls are blocked and that flaps and ailerons have a full range of motion.

On Twitter, Air Marshal Greg Bagwell (RAF Chief of Operations and Deputy Commander) commented:

Normalisation of a short cut doesn’t make it safe. What have you been doing for years that you shouldn’t have been?

UPDATE 19 June 2016: Also see: Flaps, Coffee Cups and NVG’s: A Tale of Two Safeties:

If organizational leaders wish to understand how workers adapt so that safety and operational performance may be improved they should emphasize the overall important goals and then create a climate conducive to learning.

…by gaining a better understanding of the various types of safety goals faced by line operational teams, leaders and managers may begin to understand the different types of safety employees work to create on a regular basis. This understanding is the beginning of system improvement.

We reported in June 2014 on a Royal Air Force (RAF) A330 Voyager ZZ333, that was involved in a loss of control (LOC-I) incident during a flight from Afghanistan in February 2014. The aircraft suddenly pitched nose down while in the cruise at 33,000ft. In 27 seconds, the aircraft lost 4,400ft, with a maximum rate-of-descent of approximately 15,000ft per minute, before recovering. The resulting negative g forces were sufficient for almost all of the unrestrained passengers and crew to be thrown towards the ceiling, resulting in a number of minor injuries. The aircraft diverted to Incirlik in Turkey.

The UK Military Aviation Authority (MAA) issued a preliminary report on 17 March 2014 that said investigators:

…found evidence to link the movement of the seat to the movement of the side-stick, in the form of a Digital SLR camera obstruction which was in-front of the Captain’s left arm rest and behind the base of the Captain’s side-stick at the time of the event. Analysis of the camera has confirmed that it was being used in the three minutes leading up to the event. Furthermore, forensic analysis of damage to the body of the camera indicates that it experienced a significant compression against the base of the side-stick, consistent with having been jammed between the arm rest and the side-stick unit.

The full Service Inquiry (SI) report has since been published. That SI also comment on a lack of reporting of lost loose articles in the RAF transport fleet.

In 1992 the gust locks had not been fully disengaged on a third-party DHC-4T Turbine Caribou conversion, N400NC, leading to a horrific fatal accident that killed 3.

UPDATE 23 January 2017: We are also aware of a control restriction from an unstowed EFB that fouled a helicopter collective pitch lever during night training flight.

UPDATE 19 May 2018: If you had spent 2 years rebuilding a classic Piper PA-12 you’d make the time to check the rigging of the flying controls before first flight, right? Sadly, the pilot in this fatal case study was in a rush: Too Rushed to Check: Misrigged Flying Controls

Other Resources

You may find these previous Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Crew Bag FOD Shatters Hawk Canopy

- AC-130J Prototype Written-Off After Flight Test LOC-I Overstress

- C-130 Fireball Due to Modification Error

- Inadequately Secured Cargo Caused B747F Crash at Bagram, Afghanistan

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- Beware Last Minute Changes in Plan

- Forgotten Fasteners – Serious Incidents

- UPDATE 13 November 2018: Inadequate Maintenance, An Engine Failure and Mishandling: Crash of a USAF WC-130H

- UPDATE 27 December 2018: Inadequate Maintenance at a USAF Depot Featured in Fatal USMC KC-130T Accident

- UPDATE 13 January 2019: Human Factors of the Selection of Parking Brake Instead of Speed Brake During a Hectic Approach (ERJ145 at Runway Excursion at Bristol)

- UPDATE 26 January 2019: MC-12W Loss of Control Orbiting Over Afghanistan: Lessons in Training and Urgent Operational Requirements

- UPDATE 30 October 2019: ‘Crazy’ KC-10 Boom Loss: Informal Maintenance Shift Handovers and Skipped Tasks

- UPDATE 25 April 2021: A Second from Disaster: RNoAF C-130J Near CFIT

- UPDATE 2 January 2025: Startled Shutdown: Fatal USAF E-11A Global Express PSM+ICR Accident

And in particular:

Also see our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

UPDATE 24 September 2016: See our report on an National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) study on Business Aviation Compliance With Manufacturer-Required Flight-Control Checks Before Takeoff

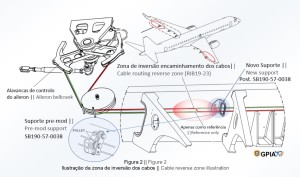

UPDATE 31 May 2019: The Portuguese accident investigation agency, GPIAAF, issued a safety investigation update on a serious in-flight loss of control incident involving Air Astana Embraer ERJ-190 P4-KCJ that occurred on 11 November 2018. The aircraft was landed safely after considerable difficulty, so much so the crew had debated ditching offshore. GPIAAF conformed that incorrect ailerons control cable system installation had occurred in both wings during a maintenance check conducted in Portugal.

GPIAFF note that: “By introducing the modification iaw Service Bulletin 190-57-0038 during the maintenance activities, there was no longer the cable routing and separation around rib 21, making it harder to understand the maintenance instructions, with recognized opportunities for improvement in the maintenance actions interpretation”. They also comment that: “The message “FLT CTRL NO DISPATCH” was generated during the maintenance activities, which in turn originated additional troubleshooting activities by the maintenance service provider, supported by the aircraft manufacturer. These activities, which lasted for 11 days, did not identify the ailerons’ cables reversal, nor was this correlated to the “FLT CTRL NO DISPATCH” message.”

GPIAFF comment “deviations to the internal procedures” occurred within the maintenance organisation that “led to the error not being detected in the various safety barriers designed” in the process. They also note that the error ” was not identified in the aircraft operational checks (flight controls check) by the operator’s crew.”

UPDATE 1 June 2019: Our analysis: ERJ-190 Flying Control Rigging Error

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Recent Comments