A Saab 2000 Descended 900 ft Too Low on Approach to Billund (Darwin Airlines HB-IZW)

On 10 December 2015 Saab 2000 HB-IZW of Darwin Airline (branded Etihad Regional but operated for on behalf of Air Berlin), that had earlier departed from Berlin Tegel, Germany, suffered a serious incident on approach to Billund, Denmark. During this approach, the aircraft descended steeply and below the minimum safe altitude prompting a Terrain Avoidance and Warning System (TAWS) warning. The aircraft diverted back to Berlin and landed safely.

Darwin Airline (Etihad Regional) Saab 2000 HB-IZW Departing from Düsseldorf in 2014 (Credit: ISORauscht CC BY-SA 4.0)

History of the Accident Flight

The Swiss Safety Investigation Board (SUST) explain in their safety investigation report that the Aircraft Commander had 8022 flying hours experience (but only 170 on type) and the co-pilot had 12100 hours experience (1022 on type). The weather in Billund that afternoon was overcast with a 600ft cloud base.

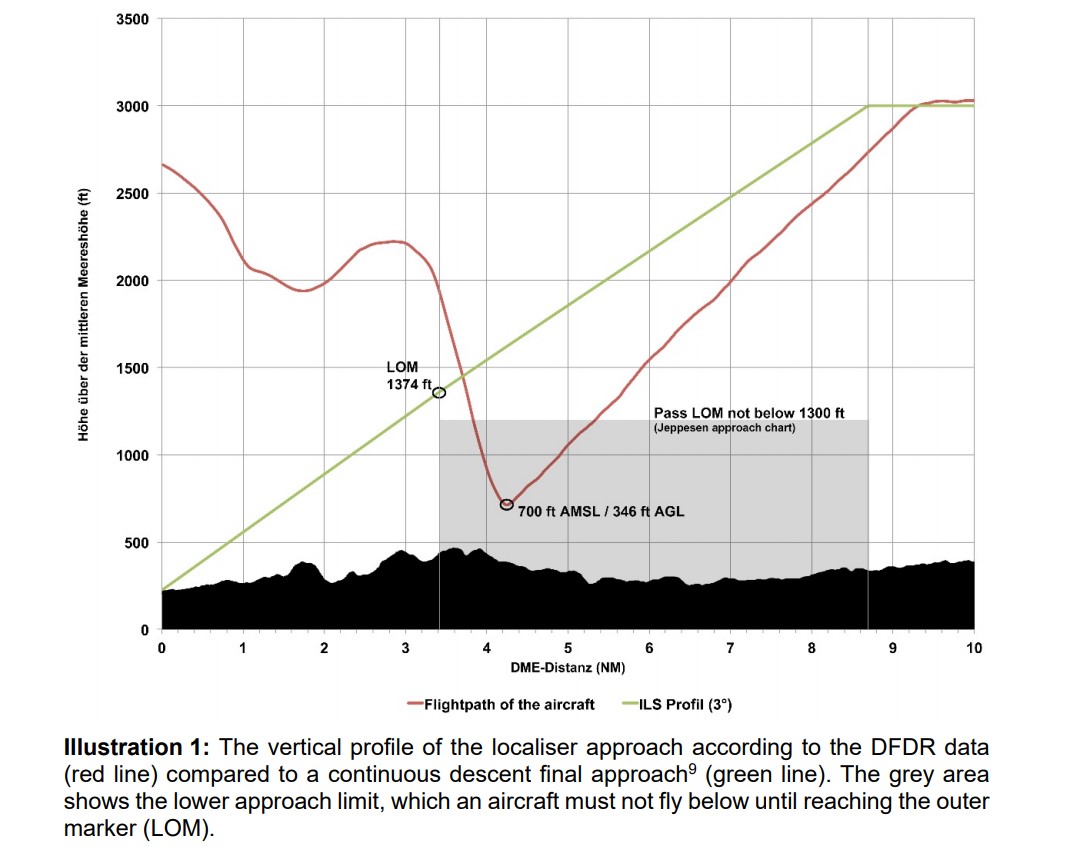

After an uneventful cruise flight, the pilots noticed problems with the glideslope indication during the approach to Billund Airport. At an altitude of 800 ft above ground and 250 ft below the minimum altitude stipulated for this position, the pilot flying [PF – the Aircraft Commander] initiated a go-around.

Because of the problems with the glideslope indication, the pilots decided to perform a non-precision approach using the localiser for the second approach.

The safety investigators report that:

During the [second] descent, the PM [Pilot Monitoring] tried to calculate the reference altitude for the correct glide path for a specified distance. He was not able to calculate this because he wanted to use the DME distance but could not find any DME information on the approach chart. He did not communicate that he was unable to come to a result and hence was not monitoring the vertical flight profile.

When the aircraft was at a DME distance of 5.5 NM and an altitude of 1240 ft AMSL, the auto-callout ‘one thousand’ sounded, meaning that the aircraft was 1000 ft above ground. According to their statements, the crew noticed at this time that something was not right, but they did not realise what was wrong. 19 seconds later, the enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS [i.e. a Honeywell TAWS]) sounded for one second with a glideslope warning.

The investigators comment that:

According to their statements, the crew was convinced that something was wrong when the auto-callout ‘five hundred’ sounded another 12 seconds later. 7 seconds later, at an altitude of 757 ft AMSL or 404 ft AGL, the PF decided to initiate a go-around. At approximately the same time, the EGPWS ‘terrain ahead, pull up’ warning sounded. The PF flew the normal go-around procedure and, one second after the EGPWS warning, the go-around mode was active.

The lowest altitude during the go-around was 700 ft AMSL or 346 ft AGL.

After they had completed an analysis of the problem, the crew decided to return to Berlin…as the weather in Berlin allowed for a visual approach. The remainder of the flight was uneventful.

The investigators say that after the flight:

After…the crew concerned made a telephone call to the company to inform them that they had to execute a go-around during the approach to Billund Airport due to receiving a false warning from the EGPWS. The aviation company’s safety manager only realised that the incident had been a serious incident during the routine flight data monitoring (FDM) of the day’s operations and reported it to the Swiss Transportation Safety Investigation Board. By this time, the DFDR and CVR recordings had already been overwritten and could no longer be used for the investigation. The FDM recordings were used instead

The Safety Investigation

The cause of the inaccurate display on HB-IZW’s glideslope transmitter indicator could not be determined with certainty. According to statements made by the Danish authorities, at the time of the incident the instrument landing system was functioning properly and was not being operated under the criteria for a low visibility approach. Given these conditions, interference to the glideslope and locator signals can occur if vehicles or aircraft are located in the protected areas. A faulty glideslope indicator generally has no influence on a localiser approach and is thus of no significance to the course of this serious incident.

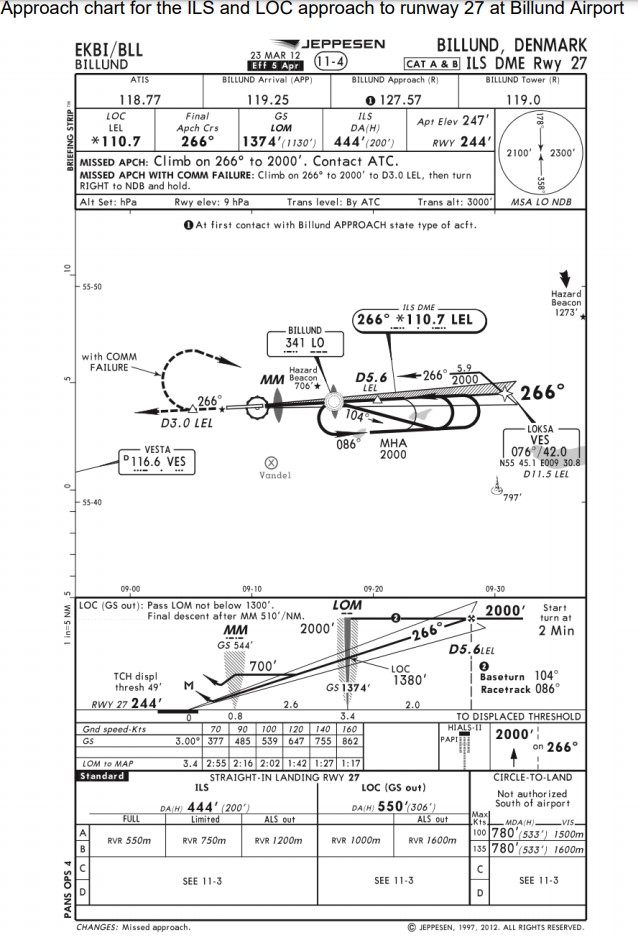

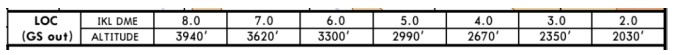

The crew were using a Jeppesen chart:

For planning the vertical flight path, the chart only shows the vertical speed for a 3º approach angle at different ground speeds. However:

A recommended altitude descent table is not displayed in this chart.

In contrast, they show an extract from the Jeppesen chart for Zurich, which gives altitudes at DME distances:

The investigators believe this would have been a better presentation format, if used consistently by Jeppesen. The investigators alos explain that in fact:

All horizontal and vertical data for a localiser approach to runway 27 at Billund Airport had already been programmed into the FMS [Flight Management System]. This would have allowed the PM to make the stipulated vertical profile visible on the PFD [Primary Flight Display] and thus to easily monitor the vertical position of the aircraft.

Remarkably:

This procedure was not known to the pilots because it was not mentioned in [Operations Manual] OM B and was not included in their training.

The investigators note that:

Since 2010, the first officer, who was then employed as a captain, had a history of shortcomings in the areas of systematics, communication and compliance with standard operating procedures (SOP). The training department tried to correct these shortcomings through discussions and additional training. After a line check in 2013, it was decided to roster him again as a first officer. Since then he has held the rank of a captain but has been flying as a first officer.

The investigators claim, based on this incident alone, that the efforts of the training department had ultimately “not been successful”.

Furthermore, the Aircraft Commander was scheduled to have a day off in Prague the day before. Instead, he made a personal trip to Berlin and only landed back in Prague at 21:32 UTC and was collected the next morning at 04:20 UTC, where ironically he flew into Berlin during the morning. During that night…

…the pilot travelled to the hotel, he had to check in and then he could go to bed…thus the pilot barely had more than 5 hours’ sleep, which possibly led to a dip in performance due to tiredness on the day of the serious incident [noting the incident occured at 13:21 UTC, 9 hours after waking].

Unfortunately the investigator’s undertake a more scientific analysis (as for example the UK AAIB did in the case of a 2002 fatal business jet accident).

The Investigator’s Conclusions

The serious incident emerged from the aircraft’s descent below the stipulated minimum altitude for a non-precision approach. Therefore, a safe altitude above the obstacles was no longer guaranteed.

The crew’s poor monitoring of the vertical flight path has been identified as the direct cause of the incident. The following factors have been identified as directly contributing to the serious incident:

- Deficient approach planning with regards to the vertical flight path.

- Reduced performance of the pilot flying, probably due to tiredness.

The approach chart, which had no distance/altitude table and thereby impeded the monitoring of the approach, systematically contributed to the serious incident.

Although it did not influence the development and course of the serious incident, the following risk factor was identified during the investigation:

- The procedure following a warning from the enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) was not consistently applied.

Safety Resources

Past Aerossurance articles that might interest you:

- AOA Anomalies on Successive B737-800 Flights

- Dash 8 Q400 Control Anomalies: 1 Worn Cable and 1 Mystery

- FOD Damages 737 Flying Controls

- HF of the Selection of Parking Brake Instead of Speed Brake During a Hectic Approach

- Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- S2000 Runway Excursion at the Start of the Take Off Roll

- ATR72 Survives Water Impact During Unstabilised Approach

- Visual Illusions, a Non Standard Approach and Cockpit Gradient: Business Jet Accident at Aarhus

- G200 Leaves Runway in Abuja Due to “Improper” Handling

- Aborted Take Off with Brakes Partially On Results in Runway Excursion

- ATR72 In-Flight Pitch Disconnect and Structural Failure

- ANSV Highlight Procedures & HF After ATR72 Landing Accident

- Safety Lessons from TransAsia ATR-72 Flight GE222 CFIT

- Fuel System Maintenance Error: Tuniter ATR72 TS-LBB Ditching 6 August 2005

- Unalaska Saab 2000 Fatal Runway Excursion: PenAir N686PA 17 Oct 2019

- Cockpit Tensions and an Automated CFIT Accident

- Southwest Unstabilised Approach Accident

- UPDATE 4 April 2021: Fatal 2019 DC-3 Turbo Prop Accident, Positioning for FAA Flight Test: Power Loss Plus Failure to Feather

- UPDATE 20 May 2023: Oil & Gas Aerial Survey Aircraft Collided with Communications Tower

We have discussed human factors and error management more generally here:

- Professor James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- Also see our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

A public inquiry chaired by Anthony Hidden QC investigated 1988 Clapham Junction rail accident. In the report of the investigation, known as the Hidden report, he commented:

There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look flawed and less sensible in the misleading light of hindsight. It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.

Recent Comments