OceanGate Titan: Toxic Culture & Fatal Hubris – An Analysis of the USCG Investigation

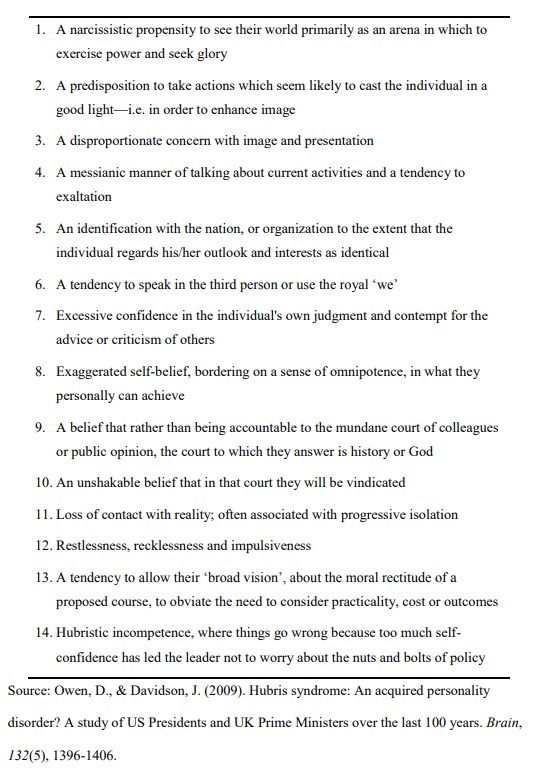

The US Coast Guard (USCG) released its Report of Investigation (ROI) on the loss of the Titan submersible, built and operated by US company OceanGate, on 18 June 2023.

OceanGate Titan Submersible (Credit OceanGate via USCG MIB)

The Titan imploded at a depth of c 3350 m after a catastrophic loss of structural integrity of the submersible’s carbon fibre hull.

Wreckage of OceanGate Titan Submersible as Found (Credit via NTSB)

This occurred during a commercial dive to the wreck of the RMS Titanic, killing five people, including Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate, and 3 fare paying passengers (or ‘Mission Specialists’ in OceanGate’s lexicon).

Viewers of the Netflix documentary Titan: The OceanGate Disaster will not be surprised that investigators commented on a toxic workplace environment within OceanGate that was the antithesis of ‘psychological safety‘.

The Hubris of Oceangate CEO Stockton Rush

It is claimed that Rush saw his company as the “SpaceX for the ocean” and in a crucial January 2018 meeting that resulted in terminating a highly experience dissenting director (discussed further below) described his approach as being “a religion”. In March 2018 the Marine Technology Society (MTS) presciently warned Rush that OceanGate’s approach, in contrast to the “diligent engineering discipline and professional approach…and adherence to a variety of safety standards” by the rest of the industry, could lead to “catastrophic” results.

“I think it was General MacArthur who said ‘You’re remembered for the rules you break’,” Rush said in one 2021 interview:

@swiftness0427 CEO Stockton Rush: “I have broken some rules to make this. (…) The carbon fiber and titanium there is a rule that you don’t do that. Well, I did.“ Titan ship built by Ocean Gate Expeditions #titan #titanic #oceangate #oceangateexpeditions #implosion

“You know I’ve broken some rules to make this [the Titan submersible]… It’s picking the rules you break that are the ones that will add value to others and add value to society”. In a Vanity Fair article in August 2023 reported that Rush declared “If you’re not breaking things, you’re not innovating,” at the 2022 GeekWire Summit, echoing the Silicon Valley ‘move fast and break things’ ethos. Rush added:

If you’re operating within a known environment, as most submersible manufacturers do, they don’t break things. To me, the more stuff you’ve broken, the more innovative you’ve been.

Vanity Fair commented:

In a culture that has adopted the ridiculous mantra “move fast and break things,” that type of arrogance can get a person far. But in the deep ocean, the price of admission is humility—and it’s nonnegotiable. The abyss doesn’t care if you went to Princeton, or that your ancestors signed the Declaration of Independence. If you want to go down into her world, she sets the rules.

Rush was a indeed a Princeton graduate with two distant relatives who had signed the US Declaration of Independence. His wife, Wendy Rush, was descended from a couple who died on the Titanic.

Rush boasted he could “buy a congressman” if needed.

The generic characteristics of hubris include:

Rush would score high against this list.

OceanGate: A Toxic Workplace Environment

This article will primarily focus on the workplace culture at OceanGate (and three organisationally focused sections [from pages of 296-304] of the USCG report) as it provides relevant lessons for safety across all high hazard industries (with key inquiry evidence and other background videos).

The USCG Marine Board of Investigation (MBI) say OceanGate:

…used firings of senior staff members and the looming threat of being fired to dissuade employees and contractors from expressing safety concerns.

In the transcript of a 19 January 2018 meeting with OceanGate’s highly experienced the Director of Marine Operations, David Lochridge, Rush said:

…there has to be some confidence in senior management… It’s not everybody’s job. Everybody at Boeing doesn’t get to sign off on the aerodynamics. Nobody see data behind certification.

Lockridge had questioned OceanGate’s structural testing and repeatedly asked to see structural integrity documentation for Titan. He had little faith in the company’s small design team, created after Rush had taken the design of Titan in house and terminated an agreement with the Applied Physics Laboratory – University of Washington. Even a former director of Engineering had likened OceanGate’s hull development to a “high-school science project”! OceanGate was evading certification of the Titan (partly because Rush had chosen unconventionally to use a composite structure for which there was no certification standards), further increasing Lochridge’s concerns (echoed a few month later in the MTS letter to Rush).

Lochridge had just completed a detailed and damning inspection report on Titan that underlined that his concerns were evidence based. Rush however treated his design choices as ‘innovative’, suggesting illusory superiority and the Dunning–Kruger cognitive biases (among others). This is reinforced by the investigators, who also note that:

Mr. Rush, who claimed that classification societies impeded innovation and regulatory agencies were not up to his technical level, intentionally operated outside the boundaries of existing regulations.

Shortly after this 2 hour meeting, Lochridge was fired and given 10 minutes to clear out his desk and exit the premises. It is evident that this meeting, which OceanGate recorded, was not intended to address Lochridge’s safety concerns but to demonstrate ‘unreconcilable differences’ to justify his termination. The termination sent a message inside OceanGate that raising safety concerns and questioning Rush would not be tolerated. Lochridge’s concerns were tragically proven on 18 June 2023.

The USCG also comment that:

OceanGate’s operations suffered from severe financial instability, high employee turnover, and a lack of professionally qualified staff, which critically undermined its ability to maintain safety and operational integrity.

It is not uncommon for ‘struggling’ organisations to suffer from several of those factors.

Our Summary of Key Section of the USCG Investigation Report

5.12 OceanGate’s Toxic Safety Culture

This section is reproduced in full with our added emphasis.

OceanGate’s operational and safety practices were critically flawed, which contributed to the catastrophic implosion of the TITAN submersible.

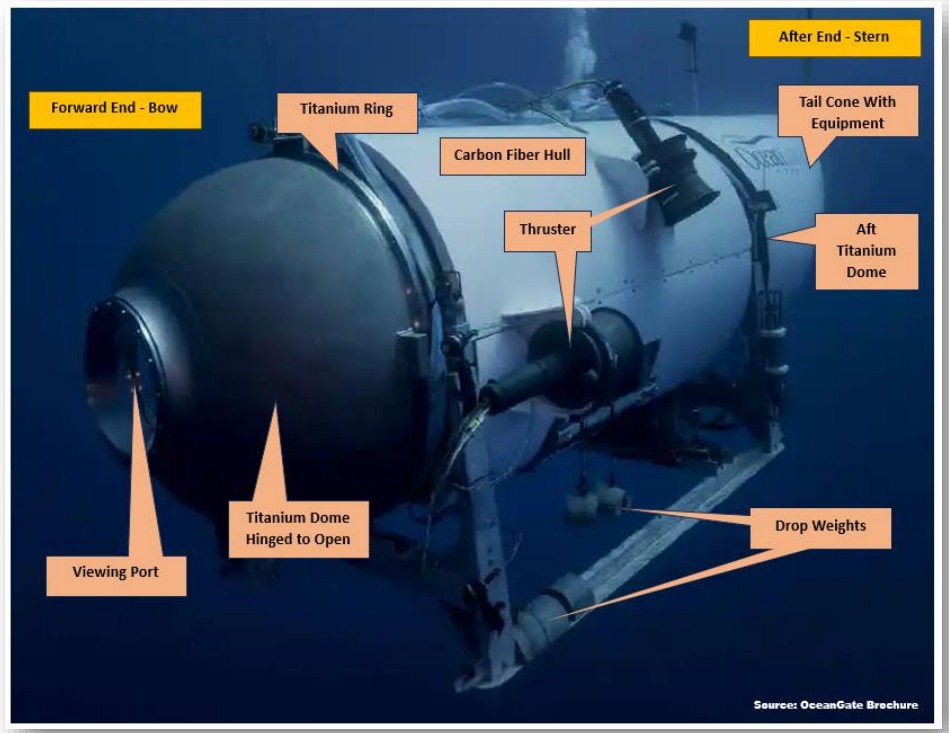

At the core of these failures was a disconnect between the company’s stated safety protocols and its actual practices.

While OceanGate’s 155-page HSE Manual was ostensibly intended to guide high-risk operations, its substance and practical application were woefully inadequate. Only four pages of the HSE manual addressed dive-specific safety procedures—a substantial shortfall for a company centered on deep-sea manned submersible operations. This highlighted systemic issues where submersible safety protocols were either egregiously inadequate or willfully disregarded, leaving critical risks unmitigated.

The analysis reveals a disturbing pattern of misrepresentation and reckless disregard for safety in OceanGate’s operation of the TITAN submersible, with Mr. Rush seemingly using inflated numbers to bolster the perceived safety and dive count of the final TITAN hull.

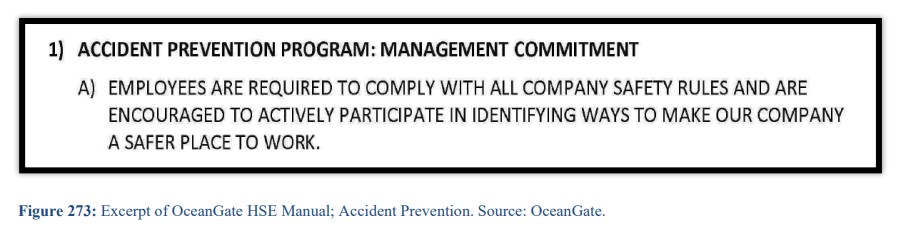

OceanGate’s cumulative dive count for the TITAN was intentionally misleading; by including the 49 dives of the scrapped original hull, they artificially inflated the operational experience of the final TITAN hull, obscuring the fact that the final TITAN hull had undergone a severely limited number of test dives (only 11, reaching a maximum depth of just 170 meters) before being used for deep-sea passenger voyages to the TITANIC wreck at 3,840 meters.

This deliberate manipulation of data created a false impression of the submersible’s proven reliability and safety, and crucially, this misrepresentation provided an inflated sense of safety and security to mission specialists. The limited testing of the final TITAN hull directly contradicts any claims of rigorous validation; a mere 11 operational dives to shallow depths is woefully inadequate to assess the structural integrity and long-term performance of a submersible designed for extreme pressures at TITANIC depths, raising serious questions about OceanGate’s adherence to established engineering practices and safety protocols.

Compounding these issues, the company’s leadership structure concentrated virtually all decision-making power in the hands of its CEO, Mr. Rush.

Although OceanGate had a Board of Directors, Mr. Rush’s dominant behavior rendered it largely ineffective. MBI witnesses described Board meetings as informational, with Mr. Rush, showcasing accomplishments and dictating decisions.

The MBI determined that OceanGate’s Board of Directors, despite the appearance of diverse expertise, in practice functioned primarily as a figurehead to add credibility to OceanGate’s operations.

The inclusion of a retired USCG admiral to help ensure their regulatory compliance was disingenuous as the retired admiral confirmed during an MBI interview that he had no marine safety background or experience when he was added to the Board. The retired USCG admiral couched the Board’s role as “strategic based,” and he confirmed that Mr. Rush “was not a person who sought, to the best of my recollection, a lot of input from the members of the Board or direction. It was mostly from Stockton, this is the plan, this is the way we’re going, and the board would discuss question, comment on, let’s say, the way ahead.”

Overall, the MBI believes Mr. Rush deliberately sidelined OceanGate’s Board and did not solicit its collective expertise so he could proceed unchecked with his vision to conduct TITANIC expeditions, regardless of any mounting safety concerns.

This style of top-down leadership, which was displayed during all OceanGate operations investigated by the MBI, fostered a culture in which operational objectives consistently overruled safety priorities.

Employees, particularly those in technical and operational roles, were dissuaded from and belittled for voicing concerns, creating an environment where safety was sidelined and concerned employees either resigned or were terminated.

A prime example of Mr. Rush’s disregard for opposing views from his senior staff was evident during his meeting with his Director of Operations [David Lochridge] on January 19, 2018, following an internal safety inspection of the first TITAN hull conducted by the Director of Operations.

After the Director of Operations made the point that OceanGate had hired him to take a conservative approach to safety, Mr. Rush made the following statement to the group assembled for the meeting, “That’s why we hired (the Director of Operations), you know. It is for that level of detail and safety approach to it, was the primary attraction to bringing (the Director of Operations) on board. And now we’ve gotten to a point where his experience and his estimation of the correct way to do is fundamentally opposite of the approach that I want to take.”

Earlier in the conversation, Mr. Rush also made the statement that he would not force people to join his “religion” if they were opposed and held opposite views. When considering that the Director of Operations was fired shortly after the meeting with Mr. Rush, the message was clear to OceanGate’s remaining senior staff that opposing views needed to be completely stifled.

The MBI also noted that many of OceanGate’s engineers lacked the specialized knowledge required for designing deep-sea submersibles, leading to significant capability and knowledge gaps.

A former OceanGate Director of Engineering described the building and operation of the first TITAN hull as akin to a “high school project,” underscoring the inadequacy of the team’s skills and experience.

Despite these shortcomings, engineers were pressured by Mr. Rush to meet ambitious deadlines, often at the expense of addressing critical design and engineering flaws. This prioritization of the operational dive schedule left the dive support teams and TITAN submersible ill-prepared to sustain safe operations in extreme deep-sea conditions. This lack of expertise within OceanGate’s engineering team was a concern that compounded overtime as OceanGate employees with submersible and engineering experience either left the company voluntarily or were fired by Mr. Rush.

Examples of OceanGate CEO’s disdain for traditional submersible safety protocols were abundant.

For example, in one incident Mr. Rush opted to use only four bolts to secure TITAN’s 3,500-pound forward dome to the submersible, “because it took less time,” despite the design requiring 18 bolts. The Director of Engineering, at the time, raised concerns over the reduced bolts and was ignored. This shortcut became an issue during a 2021 TITANIC dive. While being hoisted onto the HORIZON ARCTIC’s aft deck, the TITAN suffered a catastrophic failure: the forward dome’s bolts sheared as it transitioned from the ramp to the horizontal surface, causing the dome to detach and fall onto the LARS [Launch and Recovery System] platform.

Dome Bolt Failure – OceanGate Titan Submersible on its LARS (Credit via USCG MIB)

While no one was injured, this incident highlighted OceanGate’s propensity to not thoroughly assess operational risks, often prioritizing operational efficiency over safety.

This dismissive approach to safety culture was not limited to engineering decisions. OceanGate’s management actively retaliated against employees who raised legitimate compliance related concerns.

In 2017, a USCG Reserve petty officer employed by OceanGate warned the company’s “front office” about regulatory non-compliance. Mr. Rush reportedly responded to concerns with hostility and the USCG petty officer claimed Mr. Rush told him that he could “buy a congressman” if the USCG ever became a problem for his TITAN operations.

In 2022, a contractor hired by OceanGate raised safety concerns about the navigation system and the way the navigation system was being utilized to track and communicate with the TITAN. Specifically, concerns were raised regarding the constant errors with the TITAN’s tracking and navigation system, which stemmed from OceanGate’s decision to also use TITAN’s tracking system as their sole communications capability with TITAN’s Communications and Tracking Team.

The same contractor also brought up concerns raised by “mission specialists” after they heard a loud bang inside TITAN while ascending close to the surface from Dive 80. When the contractor voiced their numerous safety concerns to an OceanGate Director, the Director told the contractor, “You have a bad

attitude, you don’t have an explorer mindset, you know, we’re innovative and we’re cowboys and a lot of people can’t handle that.”

The contractor who voiced the concerns was subsequently sent home from the TITANIC Survey Expedition 2022, prior to the expiration of her contract.

The employee firings sent a clear message that raising legitimate safety concerns as encouraged in an excerpt from OceanGate’s HSE included in Figure 273, was not only unwelcomed by OceanGate in practice but often led to the employee’s termination.

Thus, OceanGate employees felt that raising concerns could jeopardize their potential careers at OceanGate and in the broader submersible industry if they became labeled as a problematic employee.

Financial instability further compounded OceanGate’s challenges, introducing additional risks and pressures to an already insolvent and unsustainable business model.

Witnesses described a high turnover of employees, with full-time staff being replaced by contractors and volunteers as financial pressures mounted. By 2023, OceanGate resorted to asking employees to temporarily forgo their salaries in exchange for future repayment. The former Director of Engineering, who left OceanGate in early 2023, testified to the MBI that these economic pressures severely undermined the already low safety standards at OceanGate. “The safety was being compromised way too much,” the former Director of Engineering stated to the MBI while reflecting on the growing tension between the company’s financial struggles and its operational obligations to mission specialists who often paid years in advance for their chance at a TITAN dive to the TITANIC wreck site.

As these systemic failures escalated, OceanGate’s management remained unyielding and increased their disregard for safety.

Decisions were made unilaterally at the top, with Mr. Rush often bypassing established protocols and ignoring the concerns of other experienced OceanGate employees and contractors.

Several OceanGate employees confirmed that Mr. Rush was essentially Ocean Gate’s CEO, Safety Officer, and primary submersible pilot, which enabled him to set operational safety parameters and then make all final decisions for TITAN operations without adequate input or checks and balances from the Board of Directors, the other OceanGate employees, regulators, or third-party organizations (e.g. classification societies).

The cumulative effect was an authoritarian and toxic culture where safety was not only deprioritized but actively suppressed. This toxic environment, characterized by retaliation and belittling against those who expressed safety concerns combined with a lack of external oversight, set the stage for the TITAN’s ultimate demise.

Had OceanGate adhered to the safety standards outlined in its own HSE Manual and fostered a culture of transparency and accountability, this tragedy would likely have been averted with the final TITAN hull removed from service well ahead of its implosion. Encouraging employees to voice concerns without fear of retaliation and prioritizing safety over expediency could have prevented the sequence of events that led to the disaster.

Instead, the company’s systemic failures created an environment where risks were ignored, and consequences were inevitable.

In conclusion, OceanGate’s failure to prioritize safety stemmed from deep-rooted flaws in its leadership structure, culture, and operational practices.

It was clear during the MBI’s investigation that OceanGate’s CEO (Mr. Rush) exerted full control over every facet of the company’s operations and engineering decisions. His multiple roles (e.g. Co-founder, CEO, Secretary of the Board of Directors, Chief Pilot, primary investor, etc.) enabled him to gradually solidify his centralized and dominant control over all OceanGate decisions and operations.

This corporate structure combined with the absence of meaningful external oversight and management’s dismissive attitude toward safety concerns, created an environment that enabled TITAN to continue operating with the threat of its eventual implosion growing to almost a certainty. This tragedy serves as a stark reminder of the critical importance of prioritizing safety in high-risk operations and the devastating consequences when it is disregarded.

5.13. Undermining Authority and Overriding Established Hierarchy

This section is reproduced in part with our added emphasis, and discusses some concerning prior incidents.

According to OceanGate’s HSE Manual, the Mission Director was responsible for monitoring, directing, modifying and potentially cancelling a dive operation when it was determined that an unsafe condition existed.

As OceanGate’s key decision-maker, Mr. Rush cultivated an environment where safety concerns of the Mission Director were often dismissed, diminished, or overruled, leading to numerous hazardous situations during OceanGate’s dive excursions.

OceanGate’s leadership, particularly Mr. Rush, fostered an organizational culture that increased operational risks, where financial pressures, operational demands, and a disregard for safety measures overshadowed the Mission Director’s duties.

The April 30, 2015, test dive of CYCLOPS I [an earlier OceanGate submersible] at Everett Marina revealed critical flaws in safety culture and decision-making, particularly due to Mr. Rush’s dual role as both submersible operator and CEO. When a latch malfunctioned on the ANTIPODES [an second hand 1973 submersible], the OceanGate employee who witnessed the discrepancy raised concerns about the hatch’s improper securing; however, the Mission Director allowed the pilot (Mr. Rush) to proceed with the dive without addressing the concern.

The OceanGate near miss report for the incident highlighted how Mr. Rush’s authoritative position and the pressures created by the presence of VIP guests on the excursion created a “get it done” mentality that undermined standard safety protocols.

This pressure to proceed, despite dissenting opinions, reflected a broader organizational tendency, where operational priorities frequently overrode safety considerations. A robust safety culture requires leaders to prioritize team input and ensure all concerns are addressed before moving forward.

On May 12, 2021, during [TITAN] Dive 54 in Everett, Washington, a critical issue arose at a depth of 3 meters involving the carbon dioxide scrubber system. The pilot, who also served as OceanGate’s Director of Logistics, reported a malfunction and requested an immediate ascent. Initially, Mr. Rush denied this request to surface, despite the serious risks posed by the malfunction. The Director of Engineering subsequently intervened, urging Mr. Rush to allow the submersible to resurface to resolve the issue. After some back and forth discussion, Mr. Rush reluctantly agreed to initiate the ascent. This decision to delay a potentially time critical ascent underscored the Mr. Rush’s disregard for safety concerns, prioritizing mission continuity over crew safety.

OceanGate Titan Submersible on its Launch and Recovery System (Credit OceanGate via USCG MIB)

Another glaring example occurred on July 9, 2021, during Dive 65, when the TITAN descended to the TITANIC wreck site. During the dive, several critical equipment failures occurred, including a malfunction with the drop weight motors, which required the jettisoning of the drop weight tray to begin ascent. Despite the Mission Director’s repeated instructions to release the weight tray, Mr. Rush overruled the decision due to concerns about the potential disruption to future expeditions because there were no spare drop weight trays.

Rather than releasing the drop weight tray, Mr. Rush formulated a plan to descend back to

the ocean floor and remain there for up to 24 hours until the TITAN’s sacrificial anodes

deteriorated and released the emergency weights. Mr. Rush reportedly pressured the crew aboard TITAN during the incident to remain submerged for a prolonged period…

Although Mr. Rush eventually relented after TITAN was able to manipulate [the] tray to drop weights without losing the entire mechanism, this incident highlighted a dangerous disregard for the Mission Director’s authority and a willingness to operate TITAN at depth with multiple equipment malfunctions.

A similar disregard for safety occurred on July 15, 2022, during Dive 80, when the TITAN

was being operated by the TITANIC content expert [Paul-Henri Nargeolet] who was not an employee of OceanGate nor a qualified pilot…while the “qualified pilot” sat in the aft of the submersible. A “mission specialist” then requested that the submersible maneuver closer to the TITANIC wreckage. This maneuver resulted in one of the TITAN’s skids becoming entangled in the wreckage of the TITANIC.

While the TITANIC content expert managed to free the submersible, the decision to enter the physical wreckage raises several concerns. The primary concern is OceanGate’s lack of a risk mitigation plan for an entanglement at depth, which was highlighted by the absence of a standby ROV or secondary submersible. As a safety precaution, OceanGate’s surface support crew ordered the TITAN to return to the surface immediately after it was freed. Despite that order from the Mission Director, TITAN’s crew continued their TITANIC excursion after successfully disengaging from the entanglement. This incident casts doubt on the judgment exercised by individuals in charge of TITAN’s operations, particularly given the lack of proper controls over piloting procedures and the missing emergency contingency plans and available rescue resources…

Another serious safety concern emerged on July 19, 2022, during Dive 81, when the TITAN experienced issues with its thruster controls. During its descent, the submersible began to oscillate or “yaw” in a horizontal plane, indicating a malfunction. The pilot subsequently discovered that the thruster controls had been inadvertently reversed. While the pilot was able to eventually compensate for the improperly installed thrusters, the pilot did not report the discrepancy to the Mission Director. The failure to communicate and properly verify equipment functionality prior to dive operations and the unwillingness to abort dives during malfunctions created significant gaps in operational safety procedures at OceanGate.

These examples represent only a fraction of the incidents that occurred during TITAN’s expeditions.

There was a notable lack of adherence to incident reporting procedures, with only 12 recorded “Incident Reports” (none of which could be located by OceanGate for the MBI post-incident) logged in the company’s maintenance records. This illustrates the failure to properly document and rectify safety concerns.

The multiple failures to follow the Mission Director’s directives, the inadequate risk management practices, and the lack of essential backup equipment on standby, highlight broader systemic failures within OceanGate… The incidents surrounding OceanGate underscore a broader lesson in organizational accountability and risk management.

5.14. Absence of a Designated Director of Safety and Mismanagement of Risks

This section is reproduced in part with our added emphasis.

The investigation into OceanGate’s safety and risk assessment processes revealed several critical deficiencies that compromised the safety of their operations, particularly during expeditions to the TITANIC wreck site.

One of the most significant issues was the absence of a Director of Safety. The role of the Director of Safety is clearly outlined in the Health, Safety, and Environmental (HSE) Manual, specifically in Paragraph D of Section 1, but the investigation could not identify who held this position at OceanGate and several OceanGate employees indicated that they considered Mr. Rush to be the default Safety Officer.

This lack of a dedicated Director of Safety meant there was not a designated individual accountable for

overseeing the safety program, leading to a breakdown in safety oversight.

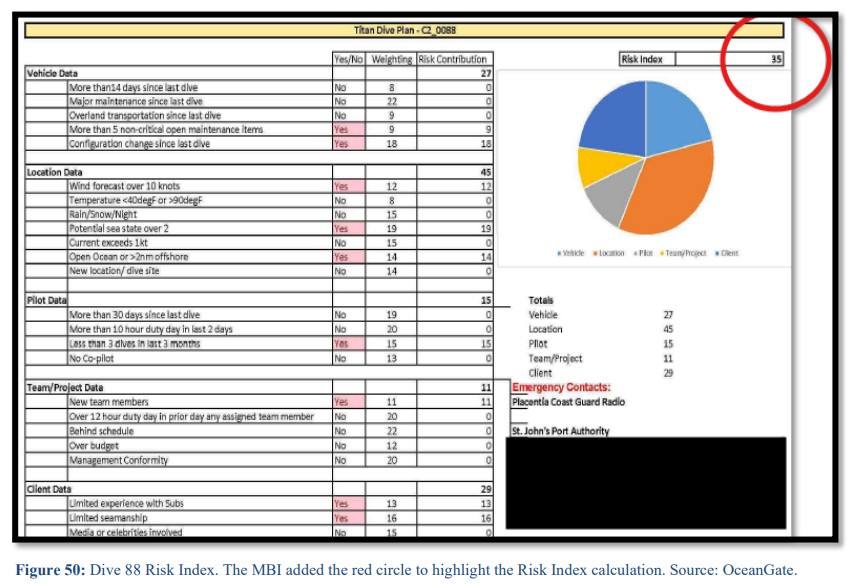

In terms of risk management, OceanGate used a system that involved a Risk Index, which considered anomalies and strikes to assess unusual events that could impact dive decisions. The Risk Index considered factors such as crew health (e.g., fatigue or illness), crew experience level, and equipment condition.

[The Risk Index is very similar to Flight Risk Assessment Tools [FRATs] that are popular in US helicopter operations that invariably after accidents are found to have scored a flight’s ‘risk’ as low and not needing higher management authorisation].

When deviations from the “perfect” situation occurred, each deviation was supposed to be counted as an anomaly with multiple anomalies being equivalent as a strike. A strike was defined in the HSE Manual as significant safety issues and if three strikes were identified then the dive was to be canceled. The MBI found no instance where an OceanGate dive was cancelled due to accumulated anomalies or strikes. While anomalies were documented in the dive logs, there was no evidence of consistent identification or documentation of strikes. Also, former OceanGate employees and others interviewed were unaware of how the Risk Index was calculated and left the assessments completely up to Mr. Rush. This lack of clarity and consistent application of the risk assessment system made is completely ineffective.

OceanGate did have a Dive Operations Risk Assessment document, which included a table categorizing various tasks by their likelihood and the severity of their consequences. This risk assessment highlighted hazards such as confined space, motion energy-collision, and entanglement in the Dive Execution Sequence. Despite these efforts, there were noticeable gaps in how certain tasks, like Tracking Operations, were assessed. For example, the risk of losing communications and tracking with the TITAN was acknowledged, but no mitigation strategies were clearly outlined.

Another significant issue was the lack of clarity with how the condition of the TITAN was assessed before dives… Based on witness interviews, the MBI determined it was unlikely the TITAN’s inner and outer hull was fully inspected while the TITAN was out of service and stored in St. John’s ahead of the TITANIC Survey Expedition 2023 operations.

The failure to classify incidents correctly also contributed to the safety failures. This raises concerns about the decision-making process and whether safety issues were adequately considered before continuing the dive.

In conclusion, the investigation revealed multiple flaws in OceanGate’s safety and risk management protocols.

The lack of a Director of Safety created ambiguity in authority and accountability over safety protocols, while the risk assessment system was inconsistently applied, with anomalies and strikes not properly identified or documented.

Serious incidents, like entanglement in the TITANIC’s wreckage, were not classified or reported as incidents, undermining the safety procedures outlined in the HSE Manual.

Furthermore, safety issues such as mechanical failures were not always addressed effectively, with dives continuing despite significant risks.

These deficiencies point to a broader failure in OceanGate’s safety culture, highlighting the need for clearer roles, more rigorous safety protocols, and better documentation of incidents to ensure the protection of crew and passengers in future operations.

Overall, had OceanGate appointed a Director of Safety, there would have been someone with a clear mandate to oversee safety protocols, ensure compliance with risk management practices, and intervene when necessary to prioritize the safety of life.

Such a position could have significantly reduced the likelihood of incidents and provided an essential layer of safety oversight that was absent from the company’s operations.

Our Safety Observations

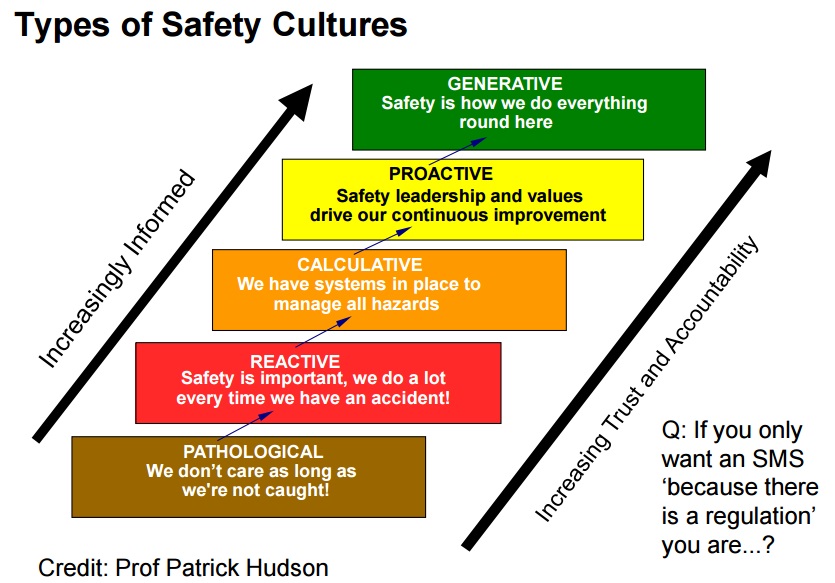

Prof Patrick Hudson proposed the following model (developed from earlier work by Ron Westrum):

When discussing this model, Hudson wittily explains why brown was chosen as the colour for the pathological. The OceanGate culture clearly was clearly in the brown…

OceanGate is an extreme example of a pathological and dysfunctional organisation. You might ask: But are there relevant lessons for other organisations? We would say: yes. While extreme, features of OceanGate’s toxic organisational dysfunction has been seen in other disasters and highlight warning signs that might help prevent future disasters.

Does this case confirm the popular management consultancy trope that its the CEO’s leadership that drives corporate culture? We would say: no. Firstly as a co-founder, Rush had a greater influence on OceanGate than the average CEO of a large organisation would have (as few CEOs have actually founded the company they lead). Secondly OceanGate was still a very small organisation (c 30 people). Thirdly, Rush was unusual in both being CEO and also simultaneously working as the most frontline employee possible (the pilot of Titan). These last two factors maximised his influence due to his persistent closeness to all employees.

The valiant efforts of David Lochridge to challenge Rush’s reckless approach do show that experienced employees will resist a reckless CEO (followship is not guaranteed!). In a larger, more conventional organisations, with a bigger pool of experienced personnel, the behaviour of a toxic CEO is likely to drive more organised resistance. We know of one ex-tech sector CEO who threw a tantrum (and furniture) when confronted by the reaction of employees during a town hall meeting at his new company in a more traditional and safety-conscious industry. That behaviour probably would not encourage candour but certainly would not encourage followship either!

More insidious though are continued recruitment and promotion policies that reinforce toxic philosophies by introducing and advancing personnel who share either supine compliant behaviour or similar thinking, intolerance to risk and hubris. High turnover of key personnel (‘nominated persons’ in UK CAA / EASA terminology) can also a sign that internal management challenge may be weak.

OceanGate does also illustrate how the established reputations of experienced individuals (non-executive board members included) and organisations can be taken advantage of by the unscrupulous (as was also seen in the Theranos scandal) as a marketing tool.

The lack of a Director of Safety (or safety function) eliminated a independent internal mechanism to act as a check and balance against Rush’s optimism and willful blindness to risk. Furthermore, as seen in many disasters, the OceanGate safety management system was mere shelfware. The OceanGate Risk Index, like most helicopter FRATs, another uncalibrated and uninsightful faux risk ritual.

While OceanGate claimed their acoustic real-time monitoring system was a key safety system, they failed to effectively analyse the data. There are strong indications of what sociologist Prof Diane Vaughan called in her book The Challenger Launch Decision the ‘normalisation of deviance’ by which in-service experience (O-ring blow by on the Space Shuttle and carbon fibre compressive damage) was rationalised and became accepted as ‘normal’ (and indeed a sign of greater resilience that originally expected).

OceanGate deliberately evaded regulatory oversight by various means. However, OceanGate was operating in plain sight and a prescient whistleblower complaint had been lodged in 2018. It does not reflect well on several regulators, including the US Coast Guard and OSHA that they did not intervene in what was a very well publicised series of submersible dives with an unregistered vessel that the wider industry had already noted concerns with. The investigators do highlight the USCG’s low experience with submersibles and OSHA‘s high whistleblower caseload. One might wonder if policies of the US administration at the time to minimise regulation had an effect or indeed whether Rush’s claim he could buy a congressman was more that a boast.

Rush’s resistance to standards and certification has also been seen with some new entrants in other fields, such as eVTOL, seeking to introduce novel technologies for which certification standards needed to be developed, who similarly want to move fast and minimise regulatory involvement (though of course there have been other cases in the more established US civil aviation industry of regulatory failures).

While the loss of life aboard Titan is tragic, its also sad that young, impressionable recruits to OceanGate had such a dysfunctional start to their careers.

An Overview of the USCG Investigation Conclusions

The USCG Marine Board of Investigation concluded the primary contributing factors:

- OceanGate’s design and testing processes for TITAN did not adequately address many of the fundamental engineering principles that would be crucial for constructing a hull to the precision necessary for the intended operations in an inherently hazardous environment

- OceanGate did not ensure an analysis was conducted to understand the expected cycle-life of TITAN’s hull

- OceanGate’s excessive reliance on a real-time monitoring system to assess the condition of the TITAN’s carbon fiber hull and then their failure to conduct a meaningful analysis of the data provided by the system

- OceanGate’s continued use of the TITAN after a series of incidents that compromised the integrity of the hull and other critical components of the submersible without properly assessing or inspecting the hull

- the TITAN’s carbon fiber hull design and construction, in terms of winding, curing, gluing, thickness of hull and manufacturing standards, introduced flaws that weakened the overall structural integrity of the TITAN hull

- OceanGate’s failure to conduct a detailed investigations after the TITAN experienced mishaps that negatively impacted its hull and components during dives conducted prior to the incident

- OceanGate’s toxic workplace environment which used firings of senior staff members and the looming threat of being fired to dissuade employees and contractors from expressing safety concerns

- OceanGate’s failure to conduct preventative maintenance on the TITAN’s hull or protect it from the elements during the extended offseason layup period ahead of the 2023 TITANIC Expedition.

The Board also cited:

- OceanGate’s safety culture and operational practices were critically flawed and at the core of these failures were glaring disparities between their written safety protocols and their actual practices

- OceanGate Chief Executive Officer’s sustained efforts to misrepresent TITAN as indestructible due to unconfirmed safety margins and alleged conformance with advanced engineering principles provided a false sense of safety for passengers and regulators

- OceanGate’s senior leaders fostered an organizational culture that allowed mounting financial shortfalls, customer expectations, and operational demands to be prioritized over the Mission Director’s authorities and responsibilities for each TITANIC dive.

- the lack of comprehensive and effective regulations for the oversight and operation of manned submersibles and vessels of novel design that are constructed and/or operated in the

United States and its navigable waterways.

The absence of a timely investigation into a 2018 whistleblower complaint by OceanGate’s former Director of Operations, David Lochridge, was also identified as a missed opportunity for regulators to intervene before the fatal dive.

Additional USCG evidence files:

Safety Resources

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Enron and the Hubris of the “World’s Leading Energy Company”

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- The Power of Safety Leadership: Paul O’Neill, Safety and Alcoa

- Culpable Culture of Compliance?

- A Railroad’s Cult of Compliance

- Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens

- Metro-North: Organisational Accidents and Shelfware

- Challenger Launch Decision – 30 Years On

- Chernobyl: 30 Years On – Lessons in Safety Culture

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns

- DC3-TP67 CFIT: Result-Oriented Subculture & SMS Shelfware

- Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- “Sensation Seeking” Survey Fatal Accident

- Regulator Missed the Chance to Intervene Before Fatal Tour Accident say TAIC

- Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

- Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire

- Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- MC-12W Loss of Control Orbiting Over Afghanistan: Lessons in Training and Urgent Operational Requirements

- Loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230 and the Haddon-Cave Review

- The Loss of RAF F-35B ZM152: An Organisational Accident

- What Lies Beneath: The Scope of Safety Investigations

- Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

- Leadership and Trust

- Safety Performance Listening and Learning – AEROSPACE March 2017

- UPDATE 20 September 2025: Cold Comfort Conference Call: USAF F-35A Alaska Accident

In another example of a pathological culture, the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reported on the 30 May 1979 Downeast Airlines DHC-6-200 Twin Otter N68DE Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident in which 17 people died. The NTSB report stated:

The Safety Board’s investigation determined that past and present company personnel perceived the company president as a particularly strong-wilted individual who dominated the course of lay-to-day operations of the company and who was the final authority in all matters. These same company personnel stated that employees who did not unquestioningly accept the president’s decisions were often subjected to various types of coercion ranging from ridicule and verbal abuse to films, seasonal layoffs, and, In some cases, dismissal. They stated that these factors, along with their observations of the president’s explosive temperament, created an atmosphere of hostility, Intimidation, and fear of loss of employment.

The Safety Board concludes that the evidence of record show: clearly a pattern of unsafe practice fostered by management that, in conjunction with a lack of emphasis by management on training, are conducive to generating accident situations. Several factors of particular significance were manifested by the reluctance of the crew to cancel he flight, even though the aircraft reportedly had an engine problem and the weather was poor. Also, the crew knew of the president’s propensity for hostility toward employees after a major problem had occurred. The flightcrew of Flight 48 knew that the recent major overhaul of the aircraft’s engines was expensive, that the right engine reportedly still was not running right, and that it had required the further expense of a replacement bleed-sir valve the day before the accident. Thus, the crewmembers would have been reluctant to subject themselves to criticism, especially since they would have been cancelling a revenue flight and grounding the aircraft away from the Downeast maintenance facility for a seemingly minor mechanical problem. This would have been against the unwritten but well understood policies of the airline president which limited the authority of flightcrews and caused them to operate the aircraft against their better judgment.

Recent Comments