A Try and See Catastrophe: Robinsion R44 LN-ORH Accident in Norway in Bad Weather

On 17 February 2019 privately operated Robinson R44 II helicopter LN-ORH crashed in bad weather in steep mountainous terrain near Eskjeflota, Ullensvang municipality, Vestland county, Norway just 5 minutes after take off. Both occupants died instantly.

Flight Preparations

The Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) explain in their safety investigation report (issued 17 June 2020) that:

On Friday 15 February 2019, the commander, accompanied by his wife flew…from their residence in Karmøy to their holiday cabin in Røldal. They were planning to return to Karmøy on Sunday afternoon.

At approximately 1100 hours on Sunday 17 February, the commander talked to one of his neighbors… As the neighbor understood it, the commander thought the weather was too bad to return home, but that it, according to the weather forecast, would improve around 1400–1500 hours.

Later he spoke with a visiting friend who was the commander’s former instructor at a helicopter pilot training school in Florida. They discussed the poor weather and several possible routes. The available meteorological information shows that the weather was “challenging” say AIBN, with “relatively strong winds, clouds down to 400 ft, drizzle and fog in several places in the relevant area”.

The commander indicated that he would make a precautionary landing should the weather deteriorate.

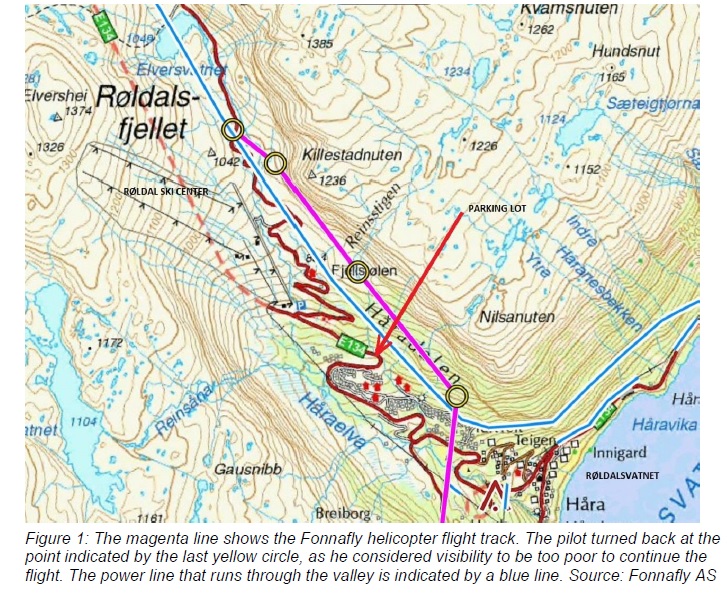

While talking, they heard and spotted a helicopter from Fonnafly AS over the ski center, heading for the valley leading to Ullshaug and Eskjeflota. This was the same route that the commander was planning to fly. Shortly after, they heard a helicopter pass and thought it was another Fonnafly helicopter heading in the same direction.

This was taken as confirmation that the preferred route was passable. It is now known the ‘second’ helicopter was actually the first Fonnafly helicopter returning having turned back due to poor visibility north west in the mountain pass.

The commander decided to conduct the flight as planned, and they all left the cabin at approximately 1500 hours. In retrospect, the friend has expressed regret to the AIBN that he did not interfere more in the decision process when they discussed the weather conditions and the imminent flight. However, he was not in a formal position to intervene.

The Accident Flight

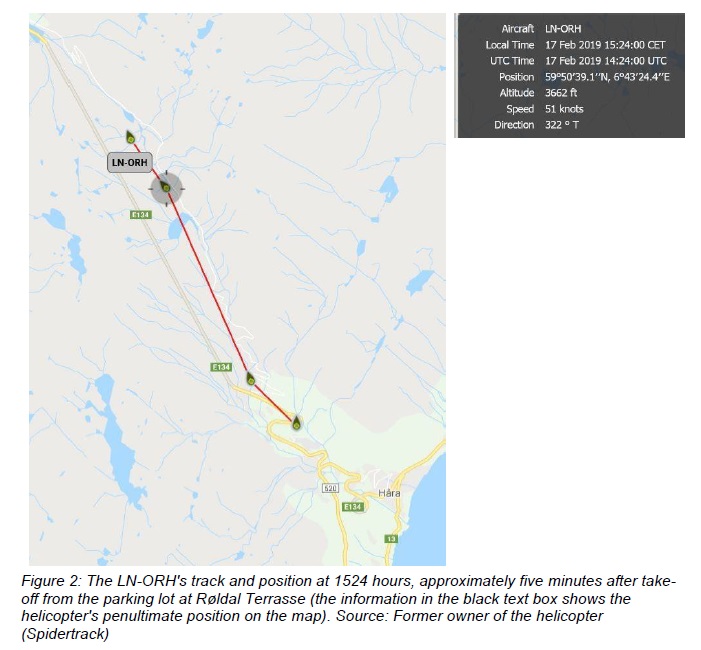

A video recording made by a witness at the ski center shows that the helicopter took off in a southwesterly direction from Røldal Terrasse at 1519 hours. It then made a right turn heading northwest in the direction of the top of the ski lift at Røldal Ski Center and Røldalsfjellet.

The commander had installed a GoPro camera on the instrument panel on the helicopter’s righthand side. The camera recorded the entire flight, from just after take-off…

The video shows that, shortly after take-off, the helicopter entered an area with low clouds and poor visibility.

R44 LN-ORH about to pass the top of the ski slope at Røldal Ski Centre. Two power line pylons can just be seen in the centre of the photo (Credit: via AIBN)

R44 LN-ORH flying along the power line at a low altitude. One pylon to the right and the

next pylon are barely visible near the middle of the photo (Credit: via AIBN)In increasingly poor visibility the flight continued for about three minutes until the commander stopped and turned the helicopter around while it was more or less hovering.

The helicopter then made a turn to the right and continued flying for about 10 seconds before all visual references disappeared from the video.

The flight continued for 84 seconds with no visual camera references outside the cockpit. The terrain became visible again for two seconds before the helicopter dived and crashed into the terrain with great force. The entire flight lasted just under 5 minutes.

The helicopter was equipped with a Kannad 406 AF Compact Emergency Locator Transmitter. The transmitter activated automatically as intended, but [as is common in helicopter accidents] the antenna cable was torn off the antenna when the helicopter crashed, and no emergency signals were therefore transmitted. The search area was established based on information from a tracker which the former owner of the helicopter still had access to.

A Royal Norwegian Air Force (RNoAF) Search and Rescue (SAR) Westland Sea King located the wreckage at around 0309.

LN-ORH crashed into a partly snow-covered escarpment near Eskjeflota in Røldalsfjellet between Røldal and Seljestad in Vestland. The mountainside faced southwest and had a slope of approximately 50°. The accident site is approx. 1,170 meters above mean sea level (3,840 ft), about 150 meters above the old road at the bottom of the mountain pass. The helicopter was equipped with four-point seat belts. The seat belts had been partly torn from their attachments as a result of the accident.

AIBN Investigation and Analysis

The commander [46] was self-employed, and his company had recently won a major contract. It had been agreed that work on this contract was to start the morning after the accident.

The commander was inexperienced. He had only 77 hours of flight experience, of which 60 were at a helicopter pilot training center in Florida, USA, in conditions that were vastly different from those encountered in the Norwegian mountains in winter. The commander also had five hours of instrument flight training. This is in no way sufficient to handle a sudden transition to instrument flying. In other words, his total experience provided a very limited basis for managing the challenges that he encountered on the day of the accident.

The applicable Standardised European Rules of the Air (SERA) regulations state:

- SERA.5001 VMC visibility and distance from cloud minima: When flying below 3,000 ft above mean sea level (MSL), flight visibility must be minimum 5 km and the aircraft must be clear of clouds. Helicopters may be permitted to operate with a flight visibility down to 1 500 m (Note: when permitted by a competent authority, this can be reduced to 800 meters). Flights operating at between 3,000 ft and 10,000 ft above mean sea level must have a minimum 5 km flight visibility. Furthermore, the distance to clouds must be 1,500 m horizontally and 300 m (1,000 ft) vertically.

- SERA.5005 Visual flight rules: minimum flight altitude is 500 ft.

AIBN says that:

The video shows that the commander flew well below the 500 ft minimum altitude and that visibility during the flight was way below the 1,500-meter requirement.

The AIBN would characterize the flight as a typical example of “pressing on” in poor weather and this may be associated with the commander’s level of experience. There is much to indicate that preparations for the flight in question were largely based on the “try and see” principle, and that their plan B was to turn back or land if the weather deteriorated. Previous accidents have shown that such alternative plans often

lead to high risks, because pilots tend to continue until visibility also is too poor to perform the landing.AIBN fails to comprehend why the commander did not recognize the danger signals and turn back or landed precautionary earlier. With this in mind, it may seem that the commander displayed a high willingness to take risks when he continued his flight into the mountain pass. Pilots with such limited experience should allow themselves wide safety margins.

The erroneous belief that two helicopters had passed that route and the former instructor’s tacit agreement may provide unjustified confidence (confirmation bias). Further is…

…the possibility that the commander’s desire to get to Karmøy on Sunday night at the latest may have influenced his decision to complete the flight. This phenomenon is known as “Plan Continuation Bias”.

AIBN define this as:

The tendency of people to continue with an original course of action in spite of changing conditions that require a new plan. The phenomenon is often observed when a person directs his or her attention toward completing a plan in order to achieve a desirable result and/or prevent negative consequences of not adhering to the plan, combined with consciously or unconsciously playing down the risk of continuing.

Our Observation

The AIBN do not specifically mention the HAI Land and Live campaign.

This is based on the entirely sensible logic that things may change during a flight and pilot’s should then “reassess the wisdom of continuing the flight and whether or not to make a precautionary landing”. HAI advises that “If your gut says land, listen! Then commit to a precautionary landing and do it”. This was launched in 2014 to “eliminate pilots’ fear of getting into trouble for landing where they had not initially planned to land”. The campaign encourages pilots and operators to sign up to a pledge to make precautionary landings when needed.

Indeed, Land and Live, and the message ‘Land the Damn Helicopter’ was immediately mentioned after a January 2020 accident with Sikorsky S-76B N72EX that killed 9, including basketball star Kobe Bryant in poor weather in California.

Radar tracking the last 1 minute of the flightpath of the Sikorsky S-76B helicopter. Google Earth image, Graphic by NTSB.

However, others, while stating that they themselves have landed in deteriorating conditions, have reflected that it may not be that effective as a safety strategy “as long as VFR helicopters are permitted and even expected to poke around at low altitudes in marginal visibility, some non-zero percentage of them will stray into IMC, and some non-zero percentage of their pilots will be unlucky ” or what is called scud-running. In fact when the NTSB released the public docket for the S-76B accident on 17 June 2020 it emerged that on 24 May 2019 that Kobe Bryant’s pilot had attended a safety meeting where a HAI article on Land the Damn Helicopter was discussed.

Significantly:

The AIBN highlight that sometimes flights commence in potentially marginal situations where the options to turn back or make a precautionary landing may actually encourage flights to commence when good airmanship would actually be to cancel or postpone the flight.

The accident also highlights the value of video evidence, even from relatively cheap and non-crash protected off-the-shelf devices to accident investigators.

Safety Resources

Robinson Safety Notice SN-44 discusses carrying passengers and the responsibilities of a pilot.

This EHEST leaflet covers the following subjects:

– Degraded Visual Environment (DVE),

– Vortex Ring State (VRS),

– Loss of Tail Rotor Effectiveness (LTE),

– Static & Dynamic Rollover, and

– Pre-flight planning Checklist.

There is also EHEST Leaflet HE 13 Weather Threat For VMC Flights:

The NTSB comment that Preparation and proficiency may help prevent accidents:

About two-thirds of general aviation accidents that occur in reduced visibility weather conditions are fatal. The accidents can involve pilot spatial disorientation or controlled flight into terrain. Even in visual weather conditions, flights at night over areas with limited ground lighting (which provides few visual ground references) can be challenging.

Preflight weather briefings are critical to safe flight. In-flight, weather information can also help pilots make decisions, as can in-cockpit weather equipment that can supplement official information. In cockpit equipment requires an understanding of the features and limitations. We often see pilots who decide to turn back after they have already encountered weather; that is too late.

Pilot’s shouldn’t allow a situation to become dangerous before deciding to act. Additionally, air traffic controllers are there to help; be honest with them about your situation and ask for help. The use of instruments, if pilots are proficient, can also help pilots navigate these challenging areas.

Other Aerossurance articles include:

- Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- An AW109SP, Overweight VIPs and Crew Stress

- Regulator Missed the Chance to Intervene Before Fatal Tour Accident say TAIC

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident

- HEMS AW109S Collided With Radio Mast During Night Flight

- Low Viz Helicopter Accident, Alaska

- Alaskan AS350 CFIT With Unrestrained Cargo in Cabin

- EC135P2 Spatial Disorientation Accident

- When Habits Kill – Canadian MD500 Accident

- RCMP AS350B3 Left Uncovered During Snowfall Fatally Loses Power on Take Off

- EC130B4 Destroyed After Ice Ingestion – Engine Intake Left Uncovered

- Stabilised Hover Prevents Loss of Control Accidents Say FAA

- Fatal Wisconsin Wire Strike When Robinson R44 Repositions to Refuel

- Fatal R44 Loss of Control Accident: Overweight and Out of Balance

- UPDATE 9 October: 2020: Latent Engine Defect Downs R44: NR Dropped to Zero During Autorotation

- UPDATE 5 February 2021: Inexperienced IIMC over Chesapeake Bay (Guimbal Cabri G2 N572MD): Reduced Visual References Require Vigilance

- UPDATE 23 October 2021: A Lethal Cocktail: Low Time, Hypoxia, Amphetamine and IMC

- UPDATE 4 December 2021: Grey Charter in French Guiana: IIMC and LOC-I

- UPDATE 12 March 2022: Black Hawk Scud Running in Tennessee: IIMC & CFIT

- Also see our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

Recent Comments