Fatal Gulf of Mexico Bell 407 Offshore Take Off Accident: Safety, Helideck & SAR / Emergency Response Questions (RLC N595RL, Walters WD106)

In 29 December 2022 Bell 407 N595RL of Rotorcraft Leasing (RLC) crashed on take off from the West Delta 106 (WD106) offshore installation in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM). The pilot and 3 passengers died.

Floating Debris (Skids and Emergency Flotation System) of RLC Bell 407 N595RL Alongside WD106 (Credit: via USCG)

On Friday 13 January 2023, the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued their preliminary report into this offshore helicopter accident.

The Accident Flight

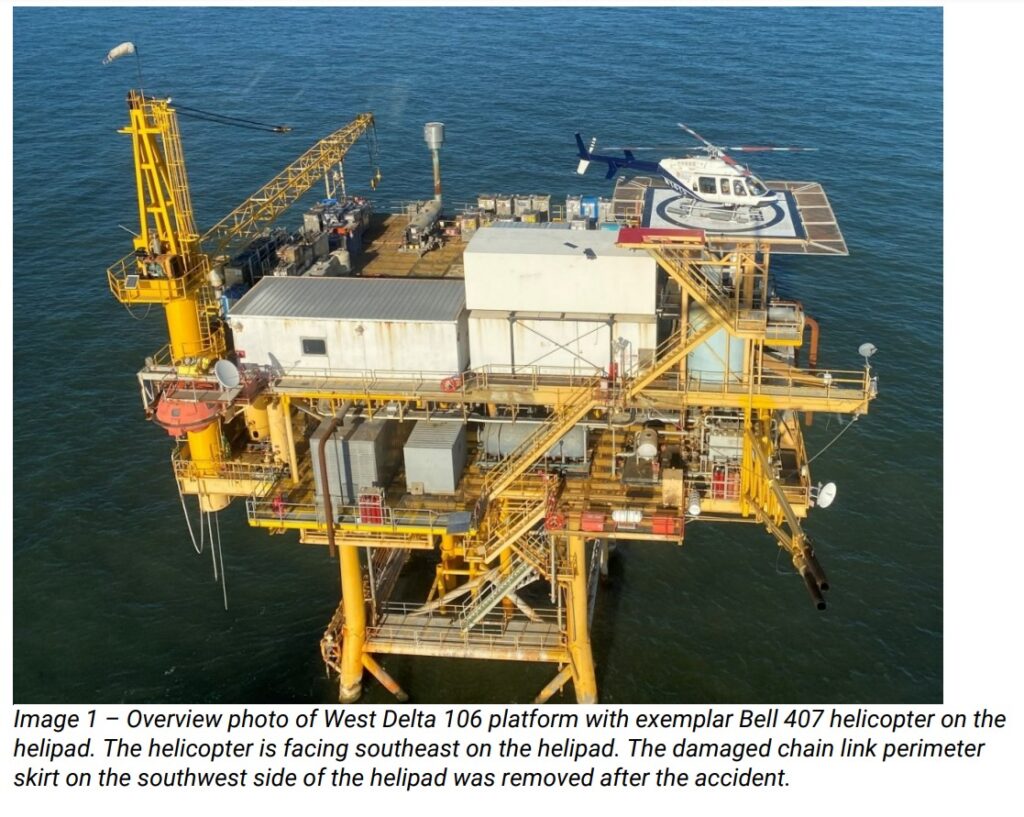

The helicopter had departed South Lafourche Leonard Miller Jr. Airport (GAO), Galliano, Louisiana with 4 passengers for WD106 on a VFR flight, 51.6 nm SE, at 07:48 Local Time. WD106 is owned by Houston based Walter Oil & Gas Corporation.

On its SE corner WD106 has a 24×24 ft square helideck, which gives a 7.3 m D-value. The B407 has a 13 m D-value so this is a small, 0.56D, sub-D deck. It also only had one stairwell. The NTSB report the deck, which was at an elevation of 100 ft, had recently been repainted and the stairwell painted red. It had a perimeter safety net (referred to by NTSB as a ‘skirt’) made of ‘chain-link’ and was marked with 8 perimeter lights (see Figure 3a below), each 8 in (20 cm) tall (current standards on decks of D<16 would limit these lights to 5 cm).

The helicopter landed at 08:25 positioned on the helideck facing SE. The 4 passengers disembarked and 3 returning passengers, employed by Island Operating Company, boarded shortly after, having had a handover discussion with the incoming personnel.

The NTSB state that:

There were no eyewitnesses or surveillance video of the helicopter’s departure from the WD106 helipad; however, there were several individuals who reported hearing the helicopter operating while on the helipad.

Although, the NTSB don’t comment, this lack of witnesses is because the helideck was being operated without a Helideck Landing Officer (HLO) & Helideck Assistants (HDAs) and therefore without fire & rescue cover. This sub-standard practice is common on small GOM installations.

These individuals noted that the helicopter’s engine continued to run after it landed on the helipad, and that they heard the engine noise increase for takeoff and then the sound of items hitting the platform.

They immediately went outside and saw the helicopter fuselage floating inverted in the water with the tail boom separated but adjacent to the fuselage. The landing skids were separated from the fuselage and the emergency skid floats were inflated.

Emergency Response

Several individuals on the platform then boarded and launched the platform’s emergency escape [freefall enclosed lifeboat] capsule, but the helicopter fuselage sunk before they could render assistance to the four occupants who remained inside the fuselage.

It appears the installation had no Fast Rescue Craft, hence deployment of the installations lifeboat, an unsuitable craft for attempting a rescue.

The US Coast Guard (USCG) were notified but curiously, despite the NTSB reporting the installation’s crew being aware the helicopter crashed alongside and early social media posts confirming the USCG were aware this was a take off accident, the USCG “searched approximately 180 square miles for 8 hours”.

It was announced on 4 January 2023 that the bodies had been recovered.

The Safety Investigation

NTSB report that:

Examination of the helipad revealed the red paint of the stairwell was gouged and scratched near the southwest end, nearest the skirted area. The skirt near the stairwell was damaged with metal posts bent and broken and the skirt wire damaged and torn.

One perimeter light, on the southwest corner separated from the helipad and was not recovered. An adjacent perimeter light, located at the center of the west edge of the helipad, was damaged and separated from the helipad.

The light’s blue glass globe was shattered, and shards were found on the deck below the helipad. The remaining perimeter lights appeared undamaged.

There were two areas of the landing pad surface with gouges in the paint. One area was located on the western area of the aiming circle and consisted of 3 linear gouges and 2 circular gouges into the paint. The other area consisted of 9 linear gouges in the paint.

Further examination of the platform revealed composite debris scattered throughout multiple decks below the helipad. Most of the scattered debris was consistent with the materials used to construct the main rotor blades. A six-foot-long portion of a main rotor blade came to rest on a metal handrail located on the deck below the helipad [see Figure 3b above].

Close examination of imagery released by the USCG suggests the main rotor blade debris was two decks below the helideck.

Damage to WD160 Helideck and Main Rotor Blade Debris of RLC Bell 407 N595RL (Credit: USCG with Highlighting by Aerossurance)

The handrail exhibited a downward bend near the location of the main rotor blade. Three pieces of lead weight, consistent with blade weights, and multiple pieces of dark tinted acrylic, consistent with the cockpit overhead windows from the helicopter, were found on the same platform deck as the main rotor blade. The acrylic shards exhibited red paint transfer consistent in color with the red paint of the stairwell.

The upper hydraulic servo cover, normally located above the cockpit, also exhibited the same red paint transfer [see Figure 3b above].

The NTSB don’t comment further but it is noticeable that the upper portion of the helicopter struck the stairwell.

Fragments of tail rotor blades were found on the deck below the helipad.

There is no comment on what the tail rotor may have struck.

There was impact damage to the left landing skid-to-aft crosstube interface.

On 2 January 2023 was the submerged wreckage was located and salvage commenced.

The Engine Control Unit (ECU) has been sent to the NTSB Vehicle Recorder Laboratory for data extraction. The flight control servo actuators are also to be subject to further examination. The NTSB note that unfortunately:

The Appareo Vision 1000 cockpit image recorder installed in the helicopter was not found at the platform or in the recovered wreckage; however, there was extensive fuselage damage in the area that the cockpit image recorder is normally mounted.

We will update this article as the NTSB release further data.

The Safety Record of Rotorcraft Leasing (RLC)

This was RLC’s third accident of 2022, and its second fatal accident of the year:

- 14 January 2022 B407 N167RL impacted the ground near Houma, Louisiana. The NTSB have yet to determine a probable cause but information released so far indicates a possible pilot incapacitation. Both occupants died.

- 15 December 2022 B206L4 N414RL fell into the sea from the Ship Shoal 105C offshore installation in the GOM after its skids got trapped in the deck edge ‘skirt’ rolled over and fell off the deck (seemingly very similar to the accident two weeks later). In this case the three occupants were rescued by the USCG from an aircraft raft.

In another case study we examined the 11 December 2008 loss of RLC B206L4 N180AL with the loss of 5 lives and, in particular, survivability issues at low sea temperature and late alerting of rescue services: So You Think The GOM is Non-Hostile? The sea temperature could be a common issue in the December 2022 accident as cold shock can prevent cabin egress.

We have previously covered the ditching of RLC’s N373RL on 11 November 2012 after a power loss on take off offshore. The four occupants in that case were uninjured.

We have also reported on an RLC accident on 25 September 2021 where B407 N662RL was lifting off for departure from a heliport in Patterson, Louisiana when and drifted backwards into B407 N668RL.

Our Observations

We would expect a competent safety investigation to consider the operator’s safety management & especially its response to the accident 2 weeks before, the suitability of sub-D decks and single engine helicopter operations, the design standards applied to helidecks, the SAR / emergency response & the survivability aspects and the FAA‘s regulation of offshore helicopter operations & BSEE‘s regulation of offshore installations.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Review of “The impact of human factors on pilots’ safety behavior in offshore aviation – Brazil”

- Fatal Mi-8 Loss of Control – Inflight and Water Impact off Svalbard

- Canadian Coast Guard Helicopter Accident: CFIT, Survivability and More

- Korean Kamov Ka-32T Fire-Fighting Water Impact and Underwater Egress Fatal Accident

- NH90 Caribbean Loss of Control – Inflight, Water Impact and Survivability Issues

- Dramatic Malaysian S-76C 2013 Ditching Video

- South Korean Fire-Fighting Helicopter Tail Rotor Strike on Fuel Bowser

- Ditching after Blade Strike During HESLO from a Ship

- US BSEE Helideck A-NPR / Bell 430 Tail Strike

- AS350B3 Ditching Japan

- GOM Helicopter Ops 2000-2019: Single Engine Usage Plummets But Fatal Accident Rate Resistant

- Air Ambulance B407 Hospital Helipad Deck Edge Tail Strike During Shallow Approach

- Gazelle Caught Out Jumping a Fence

- SAR Questions Feature in PNG AIC B427 Accident Investigation

- S-92A Collision with Obstacle while Taxying

- Helicopter Destroyed in Hover Taxi Accident

- Air Ambulance Helicopter Downed by Fencing FOD

- Ambulance / Air Ambulance Collision

- Loss of Bell 412 off Brazil Remains Unexplained

- Taxiing AW139 Blade Strike on Maintenance Stand

- Investigation into Collision of Truck with Police Helicopter

- Offshore Night Near Miss: Marine Pilot Transfer Unintended Descent

- North Sea Helicopter Struck Sea After Loss of Control on Approach During Night Shuttling (S-76A G-BHYB 1983)

- Night Offshore Training AS365N3 Accident in India 2015

- Loss of Control, Twice, by Offshore Helicopter off Nova Scotia

- Night Offshore Windfarm HEMS Winch Training CFIT (BK117C1 D-HDRJ)

- Blinded by Light, Spanish Customs AS365 Crashed During Night-time Hot Pursuit

- UPDATE 4 February 2023: S-92A Offshore Landing Obstacle Strike: CENIPA Report

- UPDATE 11 February 2023: Urgent Exit Required: A Helideck Incident (Omni Sikorsky S-76C+ PR-SEC)

The UK CAA publish the widely adopted CAP 437: Standards for offshore helicopter landing areas

Recent Comments