Friendly Fire: Civilian Shot in the Head During USAF F-16 Training

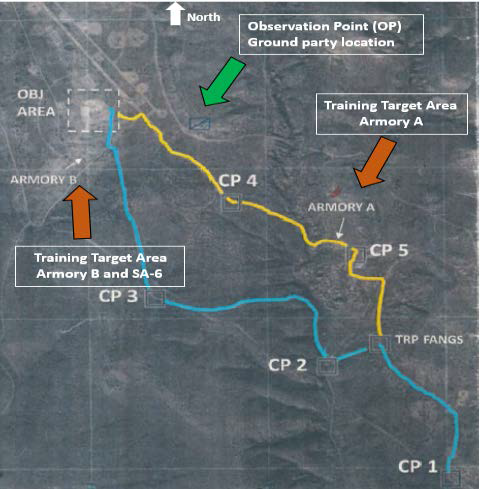

During night training, on 31 January 2017, US Air Force (USAF) Lockheed Martin F-16C 88-0496 fired 155 20mm cannon shells at the Red Rio bombing range, within the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The strafing however was not directed at the intended target, a simulated SA-8 missile site, but at the supporting Joint Terminal Attack Controller’s (JTAC) Observation Post (OP) 897 m away. A shell fragment hit a civilian contractor in the head, killing him. A US JTAC was also injured.

This accident attracted attention in October 2020 when it was reported that the contractor’s widow was awarded $24.6 million after a wrongful death court case. Follow-up reporting suggests that while $24.6 million was claimed, the family settled for less, though their lawyer stated that the family “have enough to take care of them for the rest of their lives”.

We look at the facts behind the headlines, critique a USAF human factors analysis and consider if this was a case of ‘What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find’ (WYLFIWYF).

USAF AIB Investigation

The USAF Accident Investigation Board (AIB) had previously released its investigation report. This is not a safety investigation to identify improvements but a…

…legal investigation to inquire into all the facts and circumstances surrounding this Air Force aerospace accident, prepare a publicly releasable report, and obtain and preserve all available evidence for use in litigation, claims, disciplinary action, and adverse administrative action.

Arguably such a report is not truly independent as it is written by what may be, and in this case was, a party in litigation. In contrast, safety investigation reports, the ones that identify improvements, are not publicly released by USAF (indeed the family’s claim was based heavily on the AIB report). However, the AIB report does give extensive detail to better understand the context of this accident.

Key Personnel

The AIB explain that what they term the mishap pilot (MP) and mishap instructor pilot (MIP) were from the 311th Fighter Squadron (311 FS), an F-16 training unit of the Air Education and Training Command (AETC) 54 Fighter Group (54 FG), based at Holloman AFB, New Mexico.

The MP was a USAF First Lieutenant, with 86 total flying hours, 60.9 in the F-16…enrolled in the F-16 basic course (B course). The B course is a six-month training course where first-time fighter pilots learn to fly and employ the F-16 .

The MP accumulated 6.2 hours flying with night vision goggles (NVGs) and 5 total night sorties prior to the mishap.

The squadron commander, director of operations and the MP’s flight commander testified that the MP was an average to slightly-above average student up to the night of the mishap.

He was flying his first night CAS sortie, wore Night Vision Goggles, and operated the mishap aircraft equipped with a LITENING Gen4 SE targeting pod, a 500-pound inert laser-guided bomb, and 210 rounds of 20mm TP.

The M55A1 and M55A2 target practice (TP) rounds are is ball ammunition, with a body made of steel, but hollow without a filler. The projectile itself is c 100 g. The M61 Vulcan cannon has a muzzle velocity of 1,036 m/s (3,400 ft/s).

The MIP was a USAF Captain, stationed at Holloman AFB, with 887 total flying hours, 857 F-16 hours and 107 instructor pilot hours. He is also a qualified Forward Air Controller (Airborne) (FAC(A)). This is a special qualification that allows the terminal attack control of aircraft orchestrating CAS attacks. Squadron leadership testified that the MIP was one of the squadron’s top instructors, the Company Grade Officer of the Year, and was the squadron’s top candidate for the Air Force Weapons School.

The MIP operated an F-16D configured the same as the MP’s jet…with a student observer (MSO) in the rear seat…

One of the B Course training modules is the Surface Attack Night (SAN) module, made up of a number of missions. The MP was flying the ‘SAN-3’ mission that night.

The MP previously flew the SAN-2 portion of the SAN module, on 27 January 2017, and had completed a CAS training mission, CAS-1, on 14 December 2016, both prerequisites for the MP to fly the SAN-3 (Night Close Air Support) mission.

[T]he planned SAN-3 mission included two student pilots and two instructor pilots, making up two, two-ship flights, of F-16s. The mishap flight (MF) included the MP and MIP’s F-16s, flying as one entity, under the direction of the MIP.

The MP was call sign Biggie 42 and the MIP was Biggie 41

The non-mishap flight (NMF) consisted of the second set of F-16s. The NMF flight-lead (NMF1) was the instructor, …call sign, Bolt 31. The NMF student (NMF2) flew with the call sign, Bolt 32.

The mission plan included the MIP acting in the dual roles of the MP’s instructor pilot, and as FAC(A) (a FAC(A) is an airborne qualified aviation officer who exercises control of aircraft engaged in CAS to ground troops) for both the MF and NMF.

The SAN-3 syllabus requires either a FAC(A) or a JTAC to complete the sortie, but does not require both.

As JTACs were assigned the MIP did not need to take on the extra workload of being a FAC(A).

The ground element…included a mixed party of USAF JTACs, from the 7th Air Support Operations Squadron [7 ASOS], and Dutch JTACs, from the Armed Forces of the Netherlands…accompanied by [their] liaison from the Idaho Air National Guard, 124th Air Support Operations Squadron [124 ASOS]. Located with the JTACs, were two Army ground liaison officers (GLO1 and GLO2) and…[the civilian contractor (referred to as the mishap contractor (MC)].

The JTACs involved directly in the training were…

…mishap JTAC instructor one (MJI1) with the call sign, Vandal 01 [of 124 ASOS] and a student JTAC (MJ1) with the call sign, Hustler 01, with mishap JTAC instructor two (MJI2) acting as MJ1’s instructor.

Participation in the CAS mission would enable MJI1 to receive terminal attack control currency training (to maintain certification as a JTAC, qualified JTACs must control aircraft during a live CAS mission on a regular basis), while MJ1 was completing initial JTAC training…

The civilian contractor, was reportedly an employee of Sensors Unlimited, now a division of Raytheon Technologies. He is referred to as the mishap contractor (MC) by AIB and was…

…a retired USAF Master Sergeant and former JTAC. He joined the ground element on the OP to demonstrate short-wave infrared technology.

The MC [had] coordinated with members of the Netherlands Armed Forces to accompany them during the 31 January 2017 training, so the MC could demonstrate his company’s SWIR camera.

Sequence of Events

Due to the nature of the accident, understanding the circumstances necessitates study of the build up to the exercise and the preceding elements of the flight and the complexity of the training exercise conducted.

Flight Crew Preparation

On 31 January 2017, at approximately 11:00 hours [Local Time], the MP and MIP arrived at the 311 FS. The two student pilots, the MP and NMF2, prepared and printed mission materials, after coordinating with their respective instructor pilots, MIP and NMF1. The MIP then pre-briefed both the MP and NMF2 on The Joint Application of Firepower (JFIRE) terms, definitions, and night operations specifics, in preparation for the mission.

The previous day, 30 January 2017, the MIP had coordinated with the ground element lead, MJI1, regarding the mission scenario. The MIP had used the same scripted training scenario on that previous night with another student pilot, which MJI1 and some of the Dutch JTACs also supported.

The MP, MIP and MSO filled out the 54 FG Risk Management Tool…a form used for operational risk management (ORM), utilizing a checklist of factors to identify risks associated with the planned mission, including mission, weather/environment, and human factors.

All three pilots scored as moderate on the ORM risk scale (on a scale of low, moderate, high and severe) and did not require higher than normal approval level to fly (high and severe risk levels require squadron or group commander approval to fly, respectively).

Evidence of whether this ORM tool is either accurate or effective is not discussed. Only after the tool was complete did the students attend the actual briefings for the training sortie, suggesting the ORM was not that focused on the actual operations planned.

At approximately 15:45, the 311 FS Director of Operations (DO311) conducted the mass briefing [for that night’s flying which] discussed such items as the mission execution weather forecast (MEF) and any Notice to Airmen (NOTAM)… The pilots would be using night vision goggles during the mission, and the illumination level for NVG use was forecasted as “high”.

After the mass brief:

The MIP, who wrote that night’s training scenario, briefed the mission to the other three pilots, at approximately 15:55:00. [T]he MIP covered standard flight operations, night concerns, mission scenario, weapons employment and contingencies. To get both student pilots qualified to do NVG High Angle Strafe down to a lower altitude, they were required to complete NVG Low Altitude (NVG LOWAT) qualification maneuvers. The MSO was a late addition to the mission, due to schedule changes, and did not attend the mission brief [for reasons the AIB do not explain as they had shortly before filled out the ORM Risk Management Tool].

The AIB comment that the MIP had developed a…

…complex flying plan involving handing off the student pilots back and forth between the instructors while inflight, since NMF1 was not certified to perform NVG LOWAT qualification.

The AIB’s review found elements of the authorized mission that, while not prohibited at the time, were not necessary. The squadron supervision authorized mission elements, beyond syllabus requirements, such as: 1) allowing an instructor pilot to perform FAC(A) duties and instruct a student pilot at the same time; 2) creating an expectation that students perform high-angle strafe during SAN-3, although, it is not a syllabus requirement of SAN-3; 3) interpreting syllabus requirements liberally allowing low altitude NVG qualification to occur utilizing two F-16Cs instead of one two-seat F-16D with an instructor pilot in the rear cockpit; and 4) authorizing four aircraft in two, two-ship flights during a single night CAS training sortie.

Overall, NMF1 described the MIP’s mission plan as very complex, especially for students, and not typical for night CAS.

Indeed later in the report the AIB state that NMF1 said in his statement that he was confused by the mission brief and “felt relieved when, due to the late start of Bolt Flight, they avoided the low altitude qualification portion of the mission”. Its not clear if or how NMF1 articulated this concern before the flight.

The 54 FG has a Supervisor of Flying (SOF), and a Responsible Officer (RO) during flying operations. The 311 FS has an Operations Supervisor (referred to as “Top 3”) during flying operations.

At 17:00 the four pilots met at the 311 FS operations desk for the Operations Supervisor’s (known as “Top 3”) “step brief”. DO311 was the Top 3 that night, and provided the step brief, which included the status of the airfield and runways, aircraft assignments, spare aircraft procedures, bird avoidance safety hazards, and the fire danger conditions for the scheduled ranges.

It was only at this point that the ORM risk sheets prepared nearly two hours earlier were reviewed. The AIB make no comment on whether the complex plan was discussed, or indeed if it was even recognised within the ORM risk tool, before the flight was authorised.

The crew walked to their aircraft at c17:15 and took off at 18:08.

Ground Party Preparation

On 30 January 2017, MJI1 took…Dutch JTACs, including [three the AIB designate as] DJ1, DJ2, DJ3, and the MC (who had asked MJI1 to come along), for a Holloman Ranges briefing, held at the 49th Operations Support Squadron Range Office, Holloman AFB.

RM2 [Range Manager 2] gave the range brief specifically for personnel who were JTAC-qualified. [T]he projection system was not working in the Range Conference Room…so…RM2 gave the briefing off some printed slides… The MC signed the JTAC briefing form along with the Dutch JTACs.

RM2 was familiar with MC from prior mutual military service (both were JTACs) and did not think it odd for the MC to participate in the JTAC briefing, but the RM2 was unaware at the time that the MC had also signed the briefing form. Even though the MC sat through the entire briefing, RM2 testified that he did not know or suspect that the MC was planning to go with the Dutch JTACs onto the range. RM2 noted that if he had known the MC intended to go out on the range, he would have not allowed the MC to enter the range. [It was also local practice that] non-JTAC personnel must have an approved waiver from the Range Operations Authority (ROA) prior to going on the range. However, …this waiver policy was not in the local Range instruction or other formal guidance [at the time].

MJI1 described the range briefings as short; that RM2 began by noting everyone receiving the brief were JTACs and already familiar with training ranges and that RM2 superficially covered things like local wildlife and provided warnings against picking up unexploded ordnance. MJI1 testified that there was no discussion during the range brief about who was, or was not, allowed on the range. MJI1 further testified that it was not clear to him from RM2’s range brief that local policy did not allow the MC on Red Rio Range.

MJI1 spent most of the morning of 31 January 2017 completing range entry requirements with the WSMR security office.

The size of the ground party expanded during the day:

The 7th Air Support Operations Squadron (7 ASOS), stationed at Fort Bliss, El Paso, Texas (about 1:30 hours south of Holloman AFB), had planned to do JTAC training on 30 January 2017 with the German Airforce (GAF) stationed at Holloman AFB, but the GAF had cancelled. Because MJI2 knew that the 311 FS were doing CAS missions all week, MJI2 called MJI1 and asked if they could join with MJI1’s Dutch JTACs for training. MJI1 agreed.

MJI1 [had also] invited the locally stationed Army ground liaison officers (GLO1 and GLO2) to go to the range with the JTACs to observe training that night, in recognition of their efforts in helping to coordinate the training for the Dutch.

MJI1, three Dutch JTACs (DJ1, DJ2, DJ3) and the MC left [together] from their hotel for the Red Rio Range…[in a] rented Chevrolet Tahoe [Vehicle V2]. MJI1 met GLO1 and GLO2 at the hotel, and they rode with MJI1 in his rented Toyota 4Runner (V1). The two vehicles rendezvoused at the range gate where they also met up with members of the 7th ASOS (MJ1, MJI2 and JT1) [in a Ford Econoline – V3] at approximately 17:17.

After a short drive the group arrived at the OP at c17:40.

Evidence showed that MJI1, MJI2, MJ1, GLO1, GLO2, DJ1, DJ2, and DJ3 put on some level of personnel protective equipment (PPE)…. The MC had brought protective gear with him to the range, which included Level 3 body armor and a Kevlar helmet; however, the AIB found no evidence that he ever put on his armor or helmet.

By implication JT1, a JTAC Trainee hardly mentioned in the report, was therefore also not wearing PPE. This is not commented on.

The MIP directed the MP to perform an infrared pointer aided strafe on a simulated SA-8 training target site, 900 meters away from the ground element. The MIP never verified the MP saw the intended target or the ground element’s location. For an undetermined reason, the MP disregarded his on-board sensor information, aimed at the OP and fired his gun.

When on site the ground party discussed the night’s training plan.

The plan was for MJI1 (he needed to maintain his JTAC currency to remain qualified) to control the F-16s for the first two target training events of the mission, providing terminal attack control (terminal attack control means the authority to clear the attacking aircraft to engage a target).

MJI1 would then pass control to MJ1 so MJ1 could complete his JTAC IQT, under the supervision of MJI2.

Following two or three terminal attack controls by MJ1, MJ1 would then pass control to one of the Dutch JTACs, DJ1, until the end of the mission.

The Accident Flight

The four aircraft proceeded to the Red Rio Range and contacted Vandal 01 (JTAC MJT1) at 18:21. Official sunset had been at 17:37.

At 18:23 MJI1 passed a situational update to the MF that the actual ground element was “currently established at the OP; the notional ground element (simulated friendly forces) is at contact point 1 (CP1)”.

The first targets were designated Armory A & B.

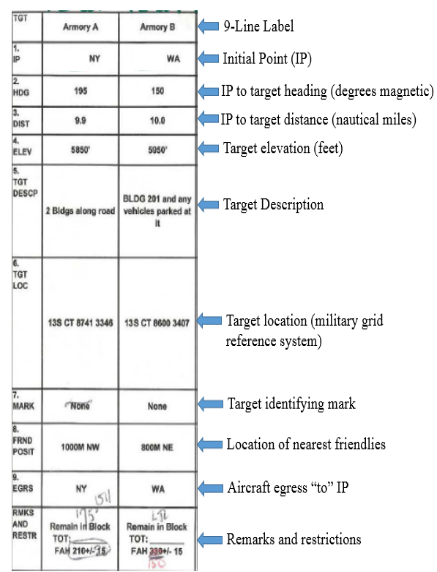

At 18:24:03 the MIP correctly read-back the target coordinates and elevation for the first two pre-planned “9-line” targets Armory A and B (a 9-line is a military standard format to quantify applicable data for a prospective target) which were actual shipping containers to MJI1.

At 18:25:18 MJI1 directed the MIP in MIP’s FAC(A) role to brief and manage the additional aircraft, NMF, arriving in the mission airspace.

At 18:29:32 MJI1 used a handheld infrared (IR) pointer to “sparkle” the first target and directed the MIP to “match sparkle” (illuminate the same location) with his aircraft’s TGP IR pointer. Both IR markers are viewable through NVGs, so by matching the IR markers it allowed both the ground based MJI1 and the airborne MIP to confirm that they were looking at the same intended target.

The MIP and MP then proceeded to the initial point (IP) prior to conducting the first attack. The first attack consisted of the MIP employing a simulated Guided Bomb Unit Twelve (GBU-12) Laser Guided Bomb (LGB) while the MP employed an actual inert GBU-12 on training target Armory A. MJI1 provided terminal control for the attack and cleared the MIP to “continue dry” (to “continue dry” means the attacking aircraft does not release weapons) since he was simulating a weapons drop and cleared the MP “hot” (“hot” means the aircraft is free to release weapons) to release his actual inert GBU-12.

At 18:36:38 hours L, the MJI1 confirmed “good effects” (good effects means the bomb effectively destroyed the target) after observing the MP’s GBU-12 hit Armory A. The MIP immediately conducted another simulated attack on training target Armory B with a simulated GBU-38 Inertially Aided Munition (IAM) after receiving another “continue dry” call from the MJI1.

The next target was a simulated Sa-6 surface-to-air missile site.

At 18:39:25…as part of the scripted scenario, the MJI1 transmitted a simulated enemy surface-to-air missile (SAM) launch aimed at the MP’s aircraft, to give the MP threat reaction training. After the MP completed threat avoidance maneuvers, the MIP directed the MP to fly his F-16 to initial point (IP) “Washington” while the MIP flew to, IP “New York,” to hold for the next attack.

At 18:40:10 MJI1 then passed terminal attack control to the next JTAC, Hustler 01 (MJ1), for the next portion of the training scenario.

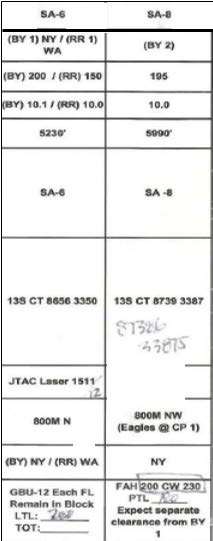

At 18:40:27 MJ1 transmitted 9-line data for training target “SA-6” (a mockup of a surface-to-air missile 6 site)…

The MIP correctly read-back the coordinates to MJ1 and the MIP proceeded to look for the target with his TGP.

At 18:50:18 the MIP called “capture” (meaning he found the target with his TGP) and confirmed the target description with MJ1.

At 18:52:13 the MP described the same target area to the MIP and confirmed he was backing up MIP’s attack. The MIP proceeded to drop an inert GBU-12 on the SA-6.

At 18:53:38 MJ1 transmitted “good effects” on the radio. The MF then established an overhead orbit near the target that they just attacked.

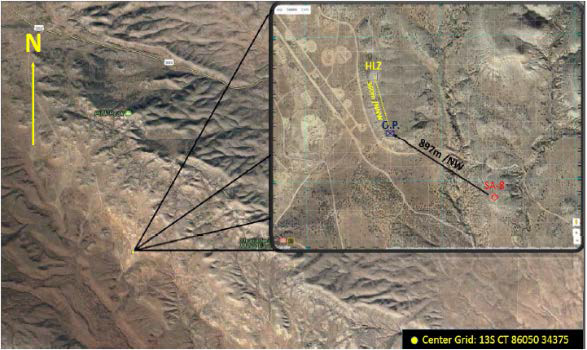

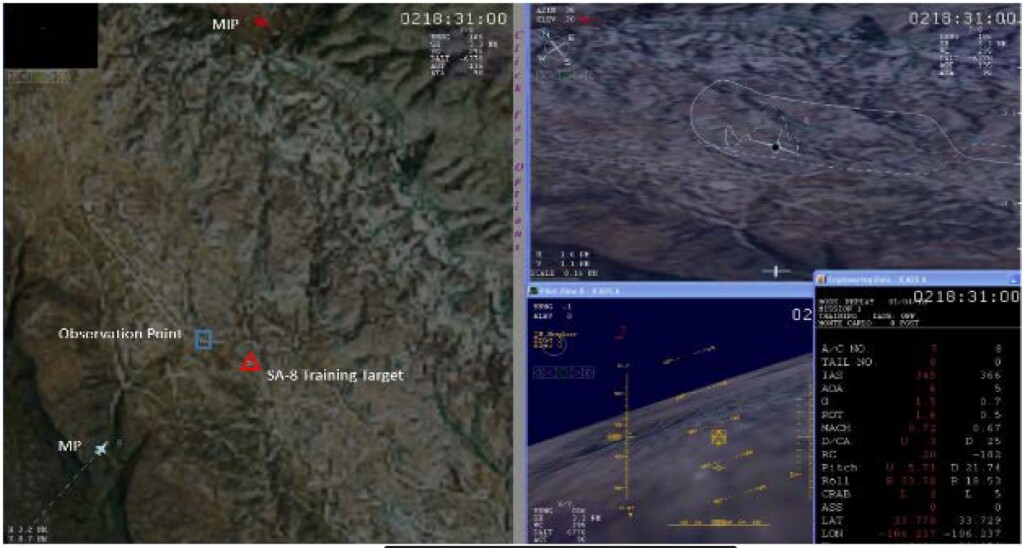

The third target was the SA-8, simulated with an actual defunct armoured personnel carrier, 897 meters to the west of the OP.

At 18:54:24 MJ1 transmitted 9-line data…to the MF [see above]. The 9-line for the SA-8 delineated a final attack heading between 200 degrees magnetic, clockwise, to 230 degrees magnetic. After the MIP acknowledged and read back the coordinates to MJ1, the MIP confirmed with MJ1 that he was “tally target,” (which meant he was able to see the intended target through his NVGs).

At 18:57:15 the MIP requested to use “high-angle” strafe (an aircraft dive angle of 25 degrees, nose low, plus or minus 5 degrees) to attack the SA-8 target…

At 18:58:00 the MIP queried MJ1 if the reciprocal heading of 020 – 050 degrees magnetic was approved (meaning to come from the opposite direction, with a final attack heading between 020 and 050 degrees, flying roughly northeast).

At 18:58:13 MJ1 approved the request and directed the MF to keep their attack “high-angle”.

At 18:58:32 the MIP told the MP to fly around to the left and make a high-angle strafe pass, but incorrectly told the MP to keep his final attack heading 215 degrees magnetic, plus or minus 15 degrees or 350 degree magnetic, plus or minus 15 degrees.

So the MIP gave the MP the heading from the Line-9 not the amended plan agreed with the JTAC.

At 18:59:00 the MP transmitted that he was “capture target”.

At 18:59:11 MJ1 transmitted he was “strobing on the observation point” (MJ1 was marking his location with an IR flashing beacon mounted on his helmet).

At 18:59:34 the MIP responded, “Biggie is visual friendlies”.

Significantly:

The MP never stated or confirmed that he too was “visual friendlies”.

The IR beacon is barely discussed by the AIB, but is a key part of clearly marking the JTAC to the fighter pilots. Coincidentally:

NMF1 checked-in with the MIP as the FAC(A), Bolt flight (NMF) having arrived in the airspace to join the training scenario. The MIP instructed the NMF to proceed to IP “Washington,” north of the SA-8 training target area.

The MIP was now sharing his attention between 3 other aircraft.

At 19:04:42 the MIP instructed the MP to position his targeting pod on the notional ground element, at contact point 3, and scan from there to the objective area.

At 19:05:18 the MIP requested terminal attack control for Bolt Flight’s attack on the SA-8 target; MJ1 approved this request. The MIP then transmitted “Biggie has control, SA-8, 9-line” at 19:05:22. The MIP requested MJ1 to take terminal attack control of the MP for a high-angle strafe attack on the SA-8 training target. At this time, the MP was not looking at the SA-8 target area.

At 19:06:45 MJ1 approved the MIP’s request. The MP’s Digital Video Recorder (DVR) shows that at this same time, the MP had moved his TGP sensor and tracked the friendly OP. The MP called “capture target” at 19:07:20 with no description of what he was actually seeing in his TGP or through his NVGs.

Before the MP could begin his strafing procedure, the MIP told the MP to “abort” his attack, at 19:08:00 to allow the NMF to attempt a bombing run on the SA-8 training target….

At 19:08:15 the MP reset his TGP by pressing “CZ” (Cursor Zero) on the TGP multifunction display. This action moved the MP’s sensors and steering data back to the intended SA-8 training target’s coordinates, and away from the JTAC’s position at the OP.

At 19:08:00 the MIP then provided terminal attack control for the NMF to drop their inert GBU-12s, but neither aircraft dropped their bombs [for reasons the AIB do not elaborate on].

The first of what would be three strafing runs were now to commence:

At 19:08:09 the MIP told the MP to setup for his attack…[and]…instructed Bolt Flight to fly back to the north. The MIP directed MJ1 that MJ1 had control of the MP for a high-angle strafe attack on the SA-8 training target, which MJ1 acknowledged at 19:10:30.

At 19:10:40 the MP transmitted “2 is ready, capture target,” relaying that he was ready to conduct the strafe attack, and that his targeting data was pointing to the correct target. At this point, a review of the MP’s DVR shows that his TGP sensor was correctly looking at the SA-8 training target

At 19:10:50 the MP called “Biggie 2 is in, 035” (meaning, the MP is commencing a high-angle strafe attack on a final heading of 035 degrees magnetic). The AIB’s review of the DVR showed the MP did not follow his steering information, which was properly guiding the MP to the SA-8 training target. Instead, he rolled out on a final heading of 019 degrees magnetic, pointing at the friendlies position on the OP, and squeezed the trigger at 19:11:13. The MP’s aircraft parameters were 2,790 feet above ground level with 408 knots (469.52 mph) indicated airspeed.

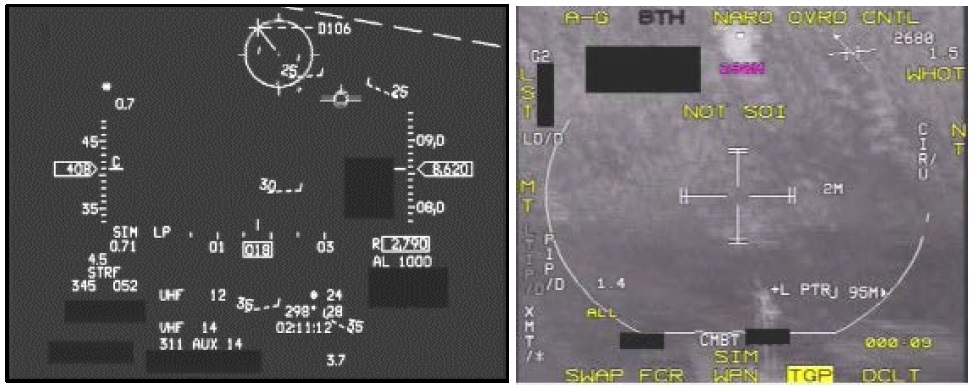

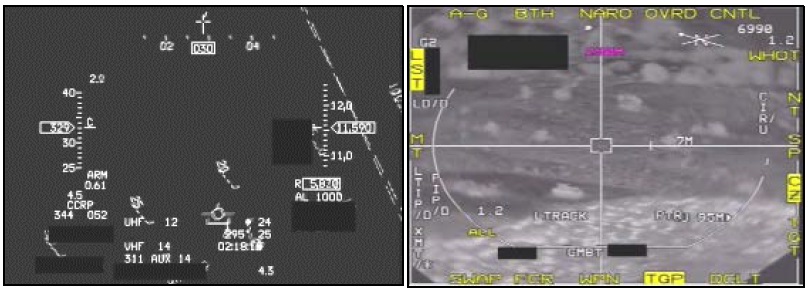

Mishap Pilot’s Head Up Display (HUD) and LITENING Gen4 SE Targeting Pod Data – First Strafe Attempt 19:11:12 (Credit: USAF AIB)

Because the MP had his master armament switch in “SIM” (simulation mode), the gun did not fire. Right after he realized the gun was in SIM, the MP, at 19:11:22, moved the master armament switch to “ARM,” enabling the trigger to fire the gun. The internal cockpit voice recorder (also called a hot mic) captured the MP expressing frustration over the master armament switching error, but the cockpit recording provides no evidence that the MP was aware that he had nearly fired upon the friendlies position.

Through this first high-angle strafe attack, the MIP was flying at approximately 15,000 feet in a right hand turn, orbiting over the SA-8 training target, between 3.5 and 4.5 nautical miles away from the MP.

The MIP was marking the SA-8 for the MP by “sparkling and lasing” the training target (the MIP used both his TGP’s IR pointer and laser to designate the target). The IR pointer is visible through NVGs and the MP had synchronized his TGP sensor to pick-up the MIP’s laser designator (the laser is not visible to the human eye, even with NVGs). For this strafe attempt, the MP’s aircraft steering data pointed at the correct target (SA-8 training target).

It does not appear the MP recognised the target he was aiming at was unmarked.

[T]he MIP directed the MP over the primary radio to setup for an immediate re-attack, which MJ1 also heard and approved, since MJ1 still had terminal control of the MP. Neither the MIP nor MJ1 verbalized any recognition or warning to the MP that the MP had been pointing at the OP and not the SA-8 training target when he attempted to fire his gun. The MIP’s only feedback was to remind the MP to make sure to check his master arming switch.

That AIB wording is a little odd as it might imply that the MIP and or MJ1 did realise MP had misidentified the target.

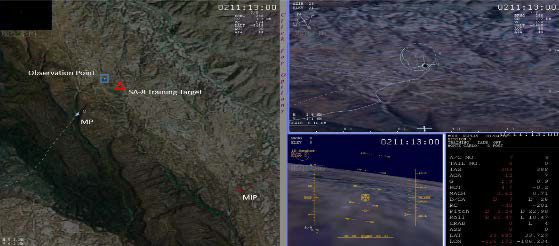

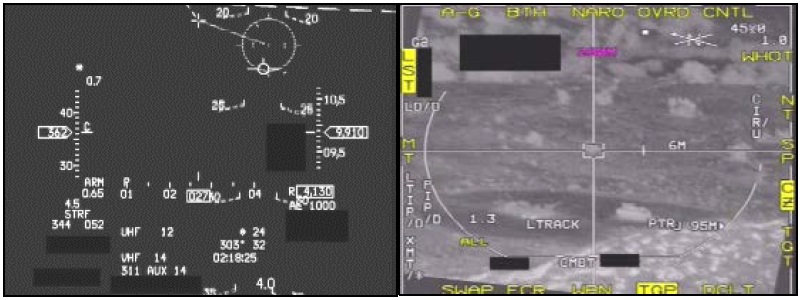

At 19:13:25 the MP made his second high-angle strafe attack attempt and called “in, heading 220”. MJ1 cleared the MP “hot” at 19:13:27 while the MIP again “sparkled” the target with his TGP’s IR pointer. The MP rolled out on an aircraft heading of 228 degrees magnetic, 26 degrees nose down, 2,610 feet above ground level with 380 knots indicated airspeed. The MP’s heads-up-display video showed a steer point “diamond” (Inertial Navigation System data) which correlated to the SA-8 training target.

Mishap Pilot’s Head Up Display (HUD) and LITENING Gen4 SE Targeting Pod Data – Second Strafe Attempt 19:13:41 (Credit: USAF AIB)

On the second high-angle strafe pass, the MP flew in accordance with his aircraft’s steering data and pointed the aircraft correctly at the SA-8 training target. However, the MP aborted the attack and did not squeeze the trigger.

The MIP subsequently queried the MP why he did not open fire during the pass and the MP responded over the intra-flight radio (heard only between the MIP and the MP) that “the sparkle just looked different so I did not want to shoot, I wasn’t uhh, it wasn’t as circular as I thought I saw, it looked like a light maybe on top of a building, I was wrong”. The MIP did not respond to the MP’s explanation or provide any cross monitoring to ensure his student pilot was on the correct target.

When MJ1 asked over the primary radio for the reason the MP did not fire, the MIP, and not the MP, responded that “Biggy 2, he’s, yeah he is going to set-up for an attack, he is going to hold south while Bolt attacks”. MJ1 and the other ground element members, who were also monitoring the primary radio, were never told that the MP thought he saw something that looked like a light on a building.

This is potentially significant as the JTAC was marking his position with an IR light on his helmet (a fact he’d broardcast to the F-16s by radio at 18:59:11).

At 19:14:15 the MIP sent the MP to hold his aircraft south of the target area while the NMF attempted for a third time to drop their inert GBU-12s on the SA-8 training target. At 19:14:36, MJ1 cleared the NMF “hot” to drop on the SA-8 training target, and then transmitted “good effects,” after observing the bombs impact the target, at 19:16:14.

Now, the third and fatal strafing run was about to commence.

At 19:16:36 the MIP asked MJ1 to approve the MP to conduct a high-angle strafe attack on the SA-8 training target for “any squirters,” (simulated enemy survivors attempting to flee from the simulated SA-8) which MJ1 approved. The MIP instructed the MP to setup for this third strafing attempt about the same time as the MP told the MIP over the intra-flight radio that he was “Joker” (meaning the MP’s aircraft had approximately five minutes of fuel before requiring a return to base).

At 19:17:00 the MIP told the NMF to stay above 17,000 feet mean sea level and to hold south of the SA-8 training target. The NMF1 responded that NMF was six nautical miles away from the SA-8 target area. The MIP then transmitted “Windmill, Biggie’s got about five-mike playtime remaining”. There is no response from the ground element. …for an unknown reason, the MIP began using the JTAC callsign for DJ1, Windmill, who was next to control from the ground party but had not yet been given control from MJ1.

At 19:17:21 the MIP told the MP that he was “lasing” the target with his TGP. The MIP told the MP “this will be TISL [Target Identification Set, Laser] strafe”. The MIP pointed his laser on the SA-8 training target so the MP could track the MIP’s laser with his TGP. This action put a cue in the MP’s HUD where the SA-8 training target was located on the ground.

At 19:17:32 the MP called to MIP that he was “spot” SA-8 (“spot” means that the MP was tracking the SA-8 training target with his TGP sensor) , with no other description of what the MP was seeing.

At 19:18:04 the MIP asked Windmill for terminal attack control of Biggy 2, noted Bolt’s position and requested Windmill to begin working additional 9-lines in the objective area. Voice data recordings revealed no response from any of the ground element granting the MIP terminal control of MP. Testimony from the ground element, however, indicated that they believed the MIP did have terminal control of the MP for this strafe attack.

At 19:18:15 the MP initiated the high-angle strafe attempt on the SA-8 training target and called that he was “in [heading] 045;” the MIP responded with “Biggie 2 cleared hot”. As the MP rolled-in for the attack, his TGP “gimbal rolled”. A “gimbal roll” is a normal and common occurrence where the TGP can no longer maintain focus or “stare” at a target because the TGP can only turn in one direction so far before it reaches its rotational limit and needs to, momentarily, reset back to center. Once the MP straightened-out of his roll, pointing at the ground, the TGP automatically re-acquired the SA-8 training target.

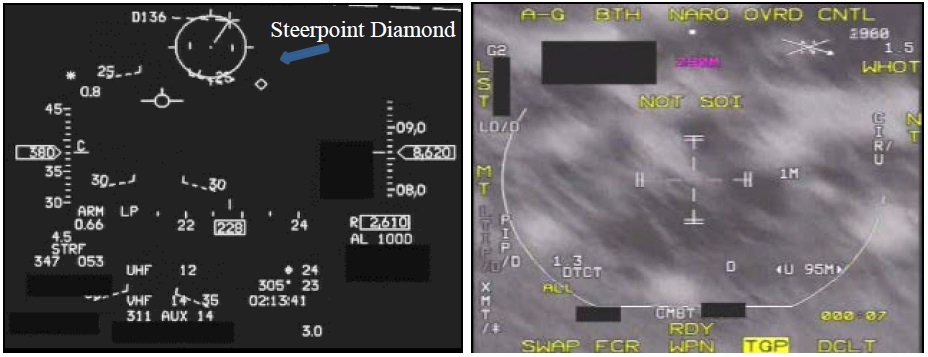

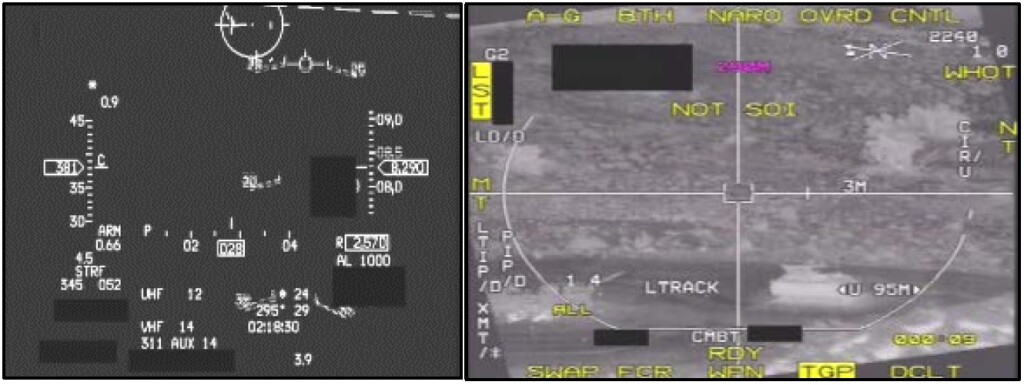

Mishap Pilot’s Head Up Display (HUD) and LITENING Gen4 SE Targeting Pod Data – Third Strafe Attempt 19:18:16 (Credit: USAF AIB)

At 19:18:16 both the TISL and steer point diamond symbology, denoting the location of the SA-8 training target, were showing in the MP’s HUD.

At 19:18:17 the TISL symbology in the MP’s HUD moved up, then down to the left. At 19:18:18 the TISL symboloy was no longer visible in the MP’s HUD.

Mishap Pilot’s Head Up Display (HUD) and LITENING Gen4 SE Targeting Pod Data – Third Strafe Attempt 19:18:18 (Credit: USAF AIB)

Data from the MIP’s targeting sensor showed that the MIP’s laser target designator and IR pointer drifted away from the SA-8 training target. Data from the MP’s TGP sensor showed the MIP’s laser spot track moved approximately 15 meters east and 4 meters north of the SA-8 training target at which time, the MP then maneuvered his aircraft further to the left to then point at the OP.

At 19:18:19 when the MP’s heads up display no longer had the TISL container or the SA-8 training target steerpoint visible, the MP’s TGP then reacquired the MIP’s laser at 19:18:25…[and]…put his aircraft into air-to-ground strafe mode, causing strafe symbology to appear in his HUD.

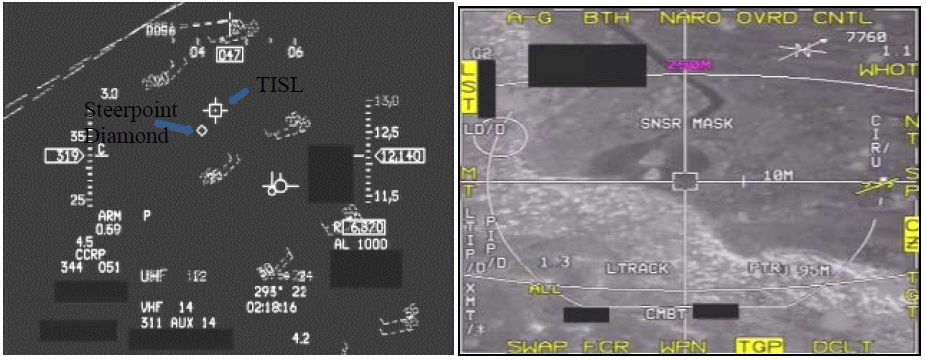

Mishap Pilot’s Head Up Display (HUD) and LITENING Gen4 SE Targeting Pod Data – Third Strafe Attempt 19:18:25 (Credit: USAF AIB)

The AIB was unable to determine what the MP was looking at to aim his F-16 toward his intended target as the SA-8 training target was no longer in the MP’s HUD; however, the SA-8 training target is in the field of view of the MP’s TGP sensor. At 19:18:30 the MP squeezed the trigger, firing 155 rounds of 20mm TP.

Mishap Pilot’s Head Up Display (HUD) and LITENING Gen4 SE Targeting Pod Data – Third Strafe Attempt 19:18:30 (Credit: USAF AIB)

The MP released the trigger at 19:18:32.

At 19:18:33 155 rounds of 20mm TP impacted the ground element’s location…

The OP (left) Showing the Attack Direction and the SA-8 Target (right) Showing the Site Layout (Credit: USAF AIB)

An unknown number of 20mm rounds impacted the three vehicles (V1, V2, V3) parked on the OP. V2 subsequently caught fire and burned.

The exact location of each of the individual members of the ground party is not recorded.

Bullet fragments hit MJ1 in the upper left leg, left buttock, and left lower back. Fragments also hit a Dutch JTAC (DJ2) who was standing behind V2, but he was not injured as the fragments hit him in an area protected by his body armor. The MC, who was not wearing his body armor or helmet, suffered a wound to the back of his head.

Immediately…MJI1 instructed MJI2 and DJ3 to identify any injured personnel.. MJI1…found MC lying on his back unconscious and unresponsive… MJI1 applied compression bandages to the MC’s wound… The ground element decided to move the MC a short distance away from the burning vehicle for safety. A UH-60 aircrew [already airborne for gunnery training on the range] extracted the MC…and transported him to Alamogordo, NM. En route to the hospital, the MC stopped breathing. GLO1 began performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with chest compressions.. At 20:21 [the helicopter] arrived at Gerald Champion… The emergency physician pronounced the MC dead at 21:01.

According to the autopsy report, the MC died from a gunshot wound to the head from a distant range with a 646-grain [42 g] projectile.

In other words the MC was hit by a single large post-first impact fragment of a 100 g round.

Human Factors Analysis

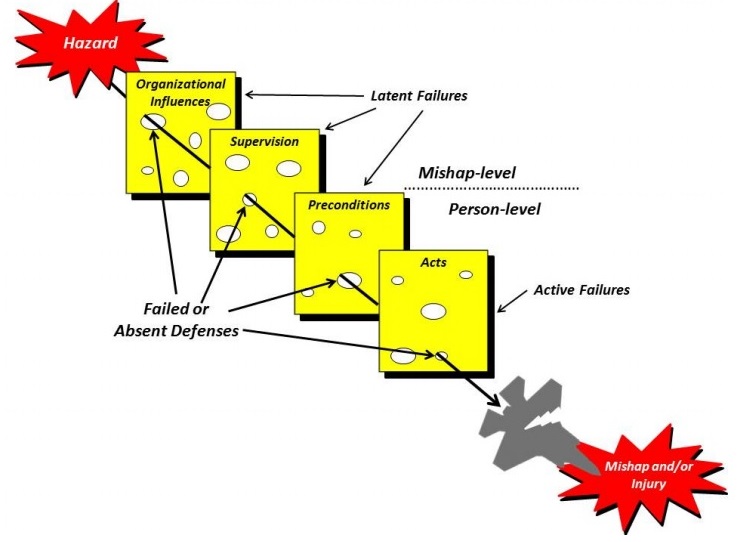

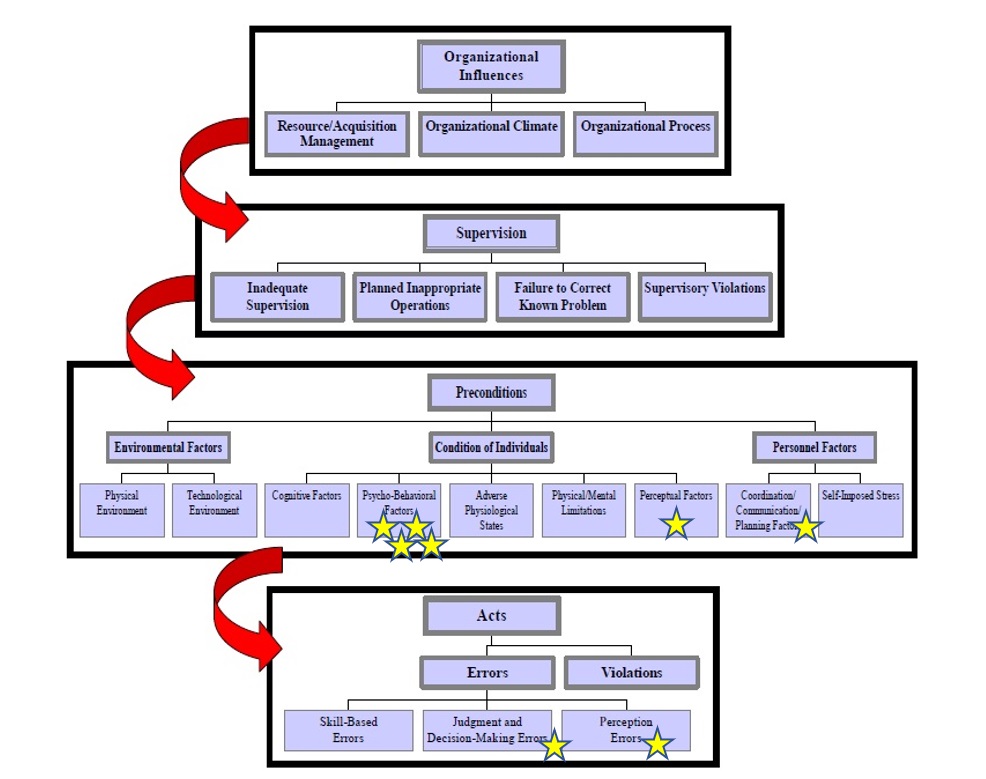

The AIB then used DoD Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) guide to evaluate the relevant human factors. HFACS has four main categories: Organizational Influences, Supervision, Preconditions, and Acts.

HFACS should encourage identifying factors beyond the ‘person level’ to consider wider, systemic organisational issues. Each is then further divided into multiple sub-categories.

While HFACS is a good taxonomy for classifying human factors and useful as an investigator’s aide mémoire during investigations, like MEDA, if it issued to guide and structure the actual investigation, can result in missing other issues and misdirecting the investigation.

The AIB coded the accident as follows (with the now superseded DoD HFACS V6 taxonomy):

Acts – AE 301 Error due to Misperception (MP): This is when “an individual acts or fails to act based on an illusion; misperception or disorientation state and this act or failure to act creates an unsafe situation”.

During the course of the MP’s strafing runs on the SA-8 training target, the evidence supports finding that the MP targeted the ground element’s position on the OP three times; and the one time that the MP correctly targeted the SA-8, he convinced himself that it was not the intended target and chose not to fire.

The AIB noted that the SA-8 training target and the OP are on similar geographical semicircular ridges with similar cleared out areas. The images from the TGP were similar in appearance between the friendly OP and SA-8 training target.

In all the AIB identified four perception errors during the strafing runs.

Pre-Conditions – PC 505 Misinterpreted/Misread Instrument (MP): This is when an “individual is presented with a correct instrument reading but its significance is not recognized, it is misread or is misinterpreted”

The MP’s avionics were correctly directing the MP to the SA-8 training target during each strafing pass, but the MP incorrectly targeted the friendly OP twice, including the fatal mishap strafe pass.

They note that:

On the fatal mishap strafe pass, the MP’s HUD displayed the TISL symbology initially, but once the aircraft had rolled out and was pointed at the friendly OP, the MP’s HUD did not display the TISL symbology nor the steer point diamond, as they were out of the HUD’s field-of-view [because] the MP’s aircraft was no longer pointing at the correct target. All video and audio data recordings suggest the avionics and TGPsystem were working appropriately.

Acts – AE 202 Task Misprioritization (MIP): Is when an “individual does not organize, based on accepted prioritization techniques, the tasks needed to manage the immediate situation”.

The AIB found evidence that the mishap instructor pilot MIP misprioritized between his responsibilities to his student pilot as an instructor pilot and the duties he was also performing during the training mission as an FAC(A). …during the multiple attacks on the SA-8 training target, the MIP provided little feedback or guidance to his student on the MP’s failed strafe attempts; the predominance of the MIP’s communications were regarding FAC(A) duties and coordinating attacks with the NMF and the ground element.

Pre-Conditions – PC 206 Overconfidence (MIP): Is when an “individual overvalues or overestimates personal capability, the capability of others or the capability of aircraft/vehicles or equipment and this creates an unsafe situation”.

Evidence obtained from testimony and in-flight communications indicate the MIP showed an overconfidence in the MP. The MIP planned a complex mission with both actual friendlies on the OP and notional friendlies that were going to be “moving” in the area throughout the mission, leaving the other instructor pilot, NMF1, after hearing the MIP’s mission pre-brief, feeling confused. The MIP’s plan required the MIP to act as both instructor pilot for the MP and FAC(A) during a night CAS training sortie involving…four aircraft.

The MIP also failed to appreciate the following challenges, showing an overconfidence in the MP’s abilities: 1) the MIP acting as a FAC(A) in addition to instructor pilot, thereby taking his attention and focus away from his instructor duties; 2) this was the MP’s first CAS mission at night; 3) this was only the MP’s second time performing high-angle strafe at night – and the previous high-angle strafe was on a lit range with clearly identified targets; 4) the MIP planned to perform low altitude NVG qualifications for both the MP and the NMF2 so they could both strafe below the minimum safe altitude (MSA); and 5) theMP previously achieved a grade of 1 for high-angle strafe, indicating the MP needed instructor guidance on subsequent high-angle strafe attempts to be proficient.

Throughout the sortie, the MIP gave non-specific directions to the MP regarding attack procedures, such as “just do a right hand turn or a left hand turn, whatever ever makes sense to get yourself in that window,” “maintain…just set up for your attack so you don’t have to … keep doing circles,” and “set-up for your attack, probably go back to the south where you are, so you can roll-in from the north on final”. These non-specific directions required significantly greater autonomy and ability on the part of the MP.

They don’t comment in their analysis on the fact that the MIP had conducted a similar SAN-3 exercise the previous night. That may have helped lull the MIP into a false sense of security.

Pre-Conditions – PC 208 Complacency (MIP): Complacency is linked with overconfience and is when an “individual’s state of reduced conscious attention due to an attitude of overconfidence, undermotivation or the sense that others ‘have the situation under control’ leads to an unsafe situation”.

In addition to the overconfidence the MIP showed in the MP, evidence revealed the MIP showed a state of reduced conscious attention to the MP during the course of the night. The MIP’s attention to the MP deteriorated as the MIP sent the MP to separate holding locations and provided minimal instruction… The MP had two failed strafing passes prior to the third mishap strafe, but the MIP did not instruct the MP about how to improve his strafing passes. The MIP only asked the MP once to say the reason he was “off dry” after his second strafe attempt. When the MP responded that the target looked different to him, but he “was wrong,” the MIP did not provide instruction or clarification…but instead told the MP to “set up for your attack”.

Pre-Conditions – PC 208 Complacency (MC):

Evidence suggests the mishap contractor displayed a level of complacency in not wearing PPE while on the Red Rio OP during a live-fire training event. The MC attended the range briefing with the Dutch JTACS where RM2 discussed Weapon Danger Zones and Minimum Safe Distances. The MC was a former JTAC, familiar with protocols for PPE requirements when near live-fire. The fact that the MC had PPE with him…supports a finding that the MC was aware of the inherent dangers of CAS live-fire training. However, for some unknown reason, the MC chose not to wear his body armor or helmet.

However:

AIB could not determine the probability of whether the MC’s injury was preventable or the severity reduced had the MC been wearing his helmet at the time of the mishap.

Pre-Conditions – PC 211 Overaggressive (MIP): This is when an” individual or crew is excessive in the manner in which they conduct a mission”.

The MIP planned a complex mission for that night’s training event…[with]…multiple elements that are not required by the 56 FW combined wingman syllabus for the SAN-3 sortie…

The MIP was also aggressive in taking terminal attack control during the mishap strafe without receiving confirmation from the ground element . Through the SA-8 training target attacks, the MIP continued to push high-angle strafe attacks for the MP to perform without providing instruction or guidance after MP’s failed attempts. The MIP also never verified that the MP was looking at the right target.

Pre-Conditions – PP 102 Cross-Monitoring Performance (MIP, MJI1 & Others): This is when “crew or team members failed to monitor, assist or back-up each other’s actions and decision”.

The AIB give examples relating to the MIP’s limited follow up with the MP after the first two aborted strafing passes. Additionally…

Members of the ground element stated that it seemed like one of the aircraft flew over the OP during one attack which the pilot aborted. The MJI1 noted this concerned him, but he thought that the MIP, as FAC(A), still had situational awareness of where the aircraft he was controlling were. None of the members from the ground element queried the MIP or MP regarding this aircraft’s position, or whether the pilot of the aircraft was visual friendlies.

Oddly, they don’t discuss the ground party’s failure to do the far easier cross-monitoring of the MC (and JT1) and PPE their use.

AIB President’s Conclusions

Cause:

…the MP misperceived that the ground element’s location was the intended simulated SA-8 training target. Additionally, the MP misinterpreted his instruments as he failed to follow his on-board systems that were directing him to the proper target.

Contributing factors:

- The MIP failed to effectively cross-monitor the MP’s performance.

- The MIP misprioritized his tasks between acting as an instructor pilot and as a FAC(A).

- The MIP demonstrated overconfidence with respect to the MP.

- The MIP demonstrated complacency.

- The MIP was overaggressive in his scenario planning and execution.

In conclusion:

I find, by the preponderance of the evidence, that the cause of the mishap was the MP’s error. The MP’s error was based on a misperception that the ground element’s location was the intended SA-8 training target at Red Rio range. Additionally, the MP misinterpreted his instruments as he failed to follow his on-board systems that were directing him to the proper target. The MIP’s failure to provide adequate supervision and instruction substantially contributed to the mishap. It is ultimately the pilot-in-command’s responsibility to positively identify the target before employing ordinance, regardless of external influences. The MP, as the qualified pilot-in-command of his F-16, was causal in this mishap.

Safety Actions (UPDATE: 4 November 2020)

It is reported that after the accident, AETC…

…immediately postponed all night vision-aided weapons releases with ground parties on weapons ranges and published updated guidance early in February 2017 to improve the safety of F-16 air-to-surface nighttime weapons employment and training.

Also students:

…must conduct their first nighttime training sortie alongside an instructor in a two-seater F-16D model…. If a D-model is not available, no live weapons are allowed onboard…

Further improvements… include how students employ the targeting pod…in conjunction with the use of night-vision goggles.

Our Observations: The Dangers of Investigations Limited to Considering ‘Blame’, ‘Culpability’ or ‘Accountability’

Ultimately, due to its charter, the AIB report does focus on who is to blame. While they use a well proven HF-centric tool like HFACS, that can still result in odd conclusions in such circumstances. In USAF RC-135V Rivet Joint Oxygen Fire we examined an investigation that paradoxically determined that a $62.4mn fire was due to a maintenance error but that no human factors were involved. That was because the error was made at a contractor and their personnel were beyond the AIB’s scope.

Early in this report the AIB identify 8 ‘major participants’ (the 4 pilots airborne [MP, MIP, NMF1, NMF2) and 4 of the 10 personnel at the OP, 3 JTAC personnel [MJI1, MJI2 and MJ1] and the fatally injured civilian [MC]). So the management of the unit, the personnel who authorised the flight and management of the range are distanced from examination. Consequently, it is not surprising that HFACS evaluation identified 6 acts and two precondtions but no supervisors or organisational factors. This is what has been termed the ‘What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find’ or WYLFIWYF principle. The issue of the complexity of the training and how, if at all, that was challenged prior to being authorised is not discussed.

Once certainly might wonder based just on the factual evidence included in the report if there were Pre-Conditions such as Self-Imposed Stress, Cognitive factors such as Confusion and a range of further Coordination / Communication / Planning issues (such as Crew/Team Leadership, Assertiveness, Challenge and Reply, Mission Planning, Mission Briefing, Task/Mission-In-Progress Re-Planning and Miscommunication). In turn supervision and planning probably deserved close consideration at the Supervisory level even before considering broader Organisational factors.

In contrast, an accident in a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) training unit resulted in a close examination of the unit, its management and culture: RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

One does also get the impression that the emphasis on the MC’s failure to wear their helmet and body armour in the AIB report is aimed at reducing a civil settlement by trying to shift some liability to the individual. Suspicion of this grows when the AIB analysis ignores cross-checking within the ground-party on PPE use and when there is one person at the OP, the JTAC Trainee (JT1), who is hardly mentioned and also appears to have not worn PPE based on careful reading of the AIB report. The facts the MC was a fiormer JTAC and had his own helmet and body armour with him are used to suggest he was aware of the risks. However, it does not appear he was issued with any PPE by the USAF and PPE is not specifically mentioned as having featured in the briefings the day before on upon arrival at the OP (potentially due to poor communication and a lack of common understanding on who was actually going on to the range).

While most organisations don’t conduct full parallel internal investigations into both the safety and the legal liability / accountability aspects of incidents, this case does show the limitations of a process that focuses on determining if a small pool of frontline personnel are individually to blame. Even though a reader may spot potential safety improvements in the factual part of the report, the areas that aren’t examined because they aren’t core to the investigation’s charter may hold even greater potential to prevent future accidents.

This is one reason we remain very wary of organisations that base their investigation processes around feeding review panels whose tools and working practices focus more on judging the level of culpability of individuals than on judging the effectiveness of proposed and enacted safety improvements. Sadly, it suits those marketing culpability decision aids to keep the focus on a ‘game of blame or no-blame’ using their proprietary tools and training at the expense of genuine learning and improvement.

Safety Resources

Scott Snook, then of the US Army wrote the classic safety book Friendly Fire (reviewed in detail here), that examined the accidental shoot down of two US Army Black Hawk helicopters on a peacekeeping mission in Iraq in 1994 by F-15s of the USAF. Sadly this type of incident is not an exception. Here, one member of the AWACS crew, not the F-15 pilots, was subject to a court marital, that was ultimately abandoned.

The US GAO published a report on the USAF invesigation into that accident: Review of U.S. Air Force Investigation of Black Hawk Fratricide Incident. Among there conclusions were that:

- The AIB report was incomplete

- Cited inaccurate testimony from senior officers

- Conatined erroneous conclusions

- ‘Perceived discipline issues’ should have been examined

Some past Aerossurance articles that you may also find enlightening:

- Inadequate Maintenance, An Engine Failure and Mishandling: Crash of a USAF WC-130H

- Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- USAF Engine Shop in “Disarray” with a “Method of the Madness”: F-16CM Engine Fire

- ‘Crazy’ KC-10 Boom Loss: Informal Maintenance Shift Handovers and Skipped Tasks

- MC-12W Loss of Control Orbiting Over Afghanistan: Lessons in Training and Urgent Operational Requirements

- USAF RC-135V Rivet Joint Oxygen Fire

- Contaminated Oxygen on ‘Air Force One’

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- High G Drama at Cold Lake

- Crew Bag FOD Shatters Hawk Canopy

- USAF Parachutist Fatally Extracted Through Ventilation Door

- USAF T-38C Downed by Bird Strike

- USAF T-6A Texan II Lost in Inverted Stall

- When Red Bull Gives You More Than Wings…

- USMC CH-53E Readiness Crisis and Mid Air Collision Catastrophe

- Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- ‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

- Loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230 and the Haddon-Cave Review

- C-130 Fireball Due to Modification Error

- HF Lessons from an AS365N3+ Gear Up Landing

- AC-130J Prototype Written-Off After Flight Test LOC-I Overstress

- C-130J Control Restriction Accident, Jalalabad

Also see:

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- Consultants & Culture: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

- Just Culture or Just Culpability?

- Complacency: A Useful Concept in Safety Investigations?

- Safety Performance Listening and Learning – AEROSPACE March 2017

Recent Comments