Fatal Flaws in Canadian Medevac Service

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) has released its investigation report into the Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT) during a flight of a medevac Piper PA-31 Navajo C-GKWE, operated by Atlantic Charters on charter to Ambulance New Brunswick (ANB), in Grand Manan, NB in darkness on the morning of 16 August 2014. The aircraft was returning from delivering a patient to St John, NB with two crew and two medical personnel aboard.

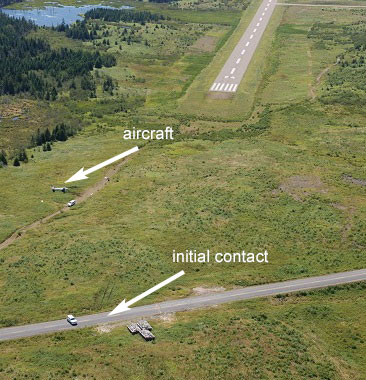

While attempting to land the crew initially conducted a missed approach. During a second approach, the aircraft touched down about 450 metres from the runway threshold. The aircraft continued through about 30 metres of brush before becoming airborne briefly and impacting left of the runway centreline about 300 metres from the threshold. the Aircraft Commander and a passenger were killed, the First Officer and the other passenger received serious injuries. The aircraft was destroyed.

The TSB made the following as to causes and contributing factors:

- The captain commenced the flight with only a single headset on board, thereby preventing a shared situational awareness among the crew.

- It is likely that the weather at the time of both approaches was such that the captain could not see the required visual references to ensure a safe landing.

- The first officer was focused on locating the runway and was unaware of the captain’s actions during the descent.

- For undetermined reasons, the captain initiated a steep descent 0.56 nautical mile from the threshold, which went uncorrected until a point from which it was too late to recover.

- The aircraft contacted a road 0.25 nautical mile short of the runway and struck terrain.

- The paramedic was not wearing a seatbelt and was not restrained during the impact sequence.

The TSB note that approach-and-landing accidents are on the their Watchlist and that this accident:

…involved several of the most common factors associated with CFIT accidents. In particular, it involved a non-precision instrument approach conducted at night over a dimly lit, sparsely populated area, and with limited visibility in fog.

This article is not going to examine the cause of the CFIT further. Instead we will look at some other factors that emerged during the TSB investigation.

The Operator

The TSB say that Atlantic Charters had been operating from Grand Manan since 1982 and:

The owner and founder of the company, who was also the occurrence captain, held the positions of accountable executive, operations manager, chief pilot and maintenance coordinator.

Atlantic Charters conducts CARs subpart 703 air taxi operations, providing domestic and international air charters. The company had been providing patient transfer charter services for over 30 years, with the majority of this work being carried out as single-pilot operations.

At the time of the accident, the company employed 5 pilots, including the owner and a member of the owner’s family. With the exception of [the family members] the company typically hired pilots with limited flying experience who normally stayed with the company for about 2 years before moving on.

Atlantic Charters did not have a safety management system (SMS), nor was it required by regulation to have one.

There was no documented flight safety program at Atlantic Charters.

The Customer

ANB’s Air Ambulance Service (‘AirCare’) consists of a contracted fixed-wing aircraft and crew. AirCare has been provided by the same operator since before ANB was established in 2007.

ANB’s contract with Atlantic Charters requires 2 pilots who are certified and qualified to operate the type of aircraft used. The 2-pilot requirement is a change that came about during the last contract negotiation (2012) with Atlantic Charters. ANB had conducted informal research and determined that 2 pilots should offer a higher level of safety; more specifically, if 1 pilot became incapacitated and could no longer perform their duties, someone else could fly the aircraft. Up until the latest contract, Atlantic Charters had been providing the ANB patient transfer service using a single pilot.

The current contract requires certain Commander and First Officer experience levels and required the operator’s flight crew training program emphasise a challenge-and-response checklist, and include cockpit resource management (which is not a regulator requirement for a Subpart 703 operation). ANB…

…indicated that it has limited aviation knowledge and experience, and was unfamiliar with what was meant by terms such as challenge-and-response and CRM.

It appears that the contractual reference to CRM on resulted in only what TSB term ‘informal’ CRM training.

The Regulator

The operator was on a 3 year inspection cycle. In the previous 3 years there had been 3 inspections, none of which examined aircraft weight and balance or continuing airworthiness.

Aircraft Configuration Discrepancies

The TSB say:

When the aircraft was imported into Canada [in April 2011], it was equipped with a Boundary Layer Research, Inc. (BLR) STC [Supplemental Type Certificate]. This STC included the installation of 4 engine nacelle strakes, 86 vortex generators (VG) affixed to the wings and vertical tail, the remarking of the airspeed indicators (ASI), and the insertion of the approved supplement into the AFM.

During the post-occurrence examination of the aircraft, it was noted that there were no VGs installed, only 2 of the engine nacelle strakes were installed, [however] both ASIs were marked in accordance with the STC markings, and the AFM included the STC supplement as well as amendments to speeds and performance charts to reflect the STC.

This implies that the anticipated performance, on which flight planning was based, would not be available. They go on:

The aircraft was equipped with an Aeromed Systems, Inc. air ambulance system…which consisted of an ambulance unit with overhead panel (referred to as a medical unit), a stretcher, and an adapter unit…[which] is approved for installation on various aircraft, including the PA-31. The STC documentation included an AFM supplement, an electromagnetic interference (EMI) test plan, and a maintenance program.

However:

TC [Transport Canada] does not have a record of Atlantic Charters incorporating this STC on the occurrence aircraft. None of the aircraft’s technical records contained any information related to the installation of the air ambulance system.

The implication is that no EMI testing was completed and the Aircraft Maintenance Programme did not include the air ambulance system’s maintenance requirements.

Role-Change Installation and Weight & Balance Deficiencies

The air ambulance STC requires an adapter unit to be installed on the right side of the fuselage, using the aircraft’s existing seat tracks. Post-accident examination revealed:

- Only the left seat track locking pin had been installed (the right hand pin had not been installed) but had been pulled free.

- The two additional quick-release pins were not installed.

- The unrestrained adapter unit had moved forward about 2 inches and was twisted.

- Of the 16 bolts which secured the 8 cross tubes, 4 were found loose in their slotted holes.

The TSB note that:

The occurrence aircraft was reconfigured from the charter to the MEDEVAC configuration the day before the occurrence flight. The pilot who installed the air ambulance system did not have approved training, nor was the pilot approved to carry out elementary work in accordance with the company’s MCM [Maintenance Control Manual].

The TSB comment that:

Atlantic Charters repeatedly reconfigured the aircraft from the passenger seating configuration to the MEDEVAC configuration. Each configuration change required an addendum to the weight and balance, and the configuration change was to be recorded in the aircraft journey log and technical records. However, there were no records of configuration changes, or the applicable weight and balance information, in the aircraft journey log or technical records.

In fact the TSB were unable to determine the aircraft’s basic empty weight, nor could it identify what equipment was included in the recorded weight of the aircraft. Therefore, the could not verify the aircraft’s weight and balance for the accident flight. Furthermore:

The company’s pre-computed weight and balance form did not include a line item to indicate nacelle fuel.

The TSB also found unrestrained medical equipment in the cabin, which impeded the First Officer’s egress.

Passenger Briefing

The ANB medical staff are not aircrew members and are legally passengers. TSB reveal:

ANB required Atlantic Charters to provide semi-annual flight safety training to paramedics in lieu of providing a safety briefing prior to takeoff at the start of each flight. However, this practice does not meet the regulatory requirements of the pilot-in-command ensuring that passengers are given a safety briefing prior to takeoff on the first flight of the day.

Operator’s Safety Culture

The TSB comment:

Atlantic Charters did not provide supporting documentation which explained the discrepancies in the weight and balance information. Maintenance tasks were being carried out without the approved training, and much of this work was not being recorded in the aircraft’s journey log. By not complying with the requirements of the STCs, the company was not ensuring that the aircraft met airworthiness standards. Because these practices had been ongoing, they would have been considered normal company practice and, therefore, a reflection of what management considered acceptable performance, i.e. the company’s safety culture.

Regulatory Oversight

The TSB comment:

TC’s surveillance activities had not identified the discrepancies in the company’s operating practices related to weight and balance and continuing airworthiness. Consequently, these practices persisted.

Customer Contract Management

…under Atlantic Charters’ latest contract, ANB had an expectation that the operation would be safer because there would be an additional pilot in the cockpit. Because of ANB’s limited aviation knowledge and experience, it relied on its service providers to ensure regulatory compliance.

ANB was unfamiliar with what was meant by standard industry terms such as challenge-and-response and CRM and, therefore, was unaware of the importance of these practices for the management of safety during flight. If organizations contract aviation companies to provide a service with which the organizations are not familiar, then there is an increased risk that safety deficiencies will go unnoticed, which could jeopardize the safety of the organizations’ employees.

Our Comments

This accident again demonstrates the importance of intelligent contracting for air services and conducting effective assurance both before and after contract award, especially when using small operators with limited organisational capabilities. It also shows that an expectation of thorough regulations and an active regulator may not be the case.

Other Resources:

- Catastrophe in the Congo – The Company That Lost its Board of Directors When you charter aircraft, any fatal air accident can leave a terrible scar. In 2010 a mining company lost its entire board of directors in the Congo. We look at the mistakes made and ineffective assurance.

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident TSB report on the forced landing of a DC-3 after an engine failure on 2013. They highlight operational non-compliances, ineffective regulatory oversight and the operator’s culture.

- HEMS Black Hole Accident: “Organisational, Regulatory and Oversight Deficiencies” TSB say the operator had insufficient resources to effectively manage safety. The regulator had concerns but its approach did not ensure timely rectification.

- Medevac Misadventure – Inquest in the Yukon A Coroner recommended a review of procedures for medical evacuations following the death on board an air ambulance of a 31 year-old woman. In particular the wrong IV tubing was taken on the aircraft as different sizes tubes were stored in the same storage location. This is a classic human performance influencing factor that increases the risk of human error.

- Dutch Safety Board Investigation: “Medical Assistance on the North Sea” The DSB find coordination centre medical support for a SAR crew inadequate in an incident in which a sports diver died.

- Dim, Negative Transfer Double Flameout We look at another HEMS incident with major human factors and modification aspects.

- C-130 Fireball Due to Modification Error

- Night Offshore Winching CFIT A German HEMS unit attempts night offshore winching and suffer a fatal accident.

- US Police Helicopter Night CFIT: Is Your Journey Really Necessary?

- US HEMS Accident Rates 2006-2015

- More US Night Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) Accidents

- Life Flight 6 – US HEMS Post Accident Review

- Operator & FAA Shortcomings in Alaskan B1900 Accident NTSB raise issues with the FAA approach to regulation.

- Wait to Weight & Balance – Lessons from a Loss of Control

- Misloading Caused Fatal 2013 DHC-3 Accident

- Misfuelling Accidents Three occasions when fixed wing aircraft were filled with the wrong fuel, including a fatal fixed wing air ambulance accident in the US.

- UPDATE 19 August 2016: Canadian KA100 Fuel Exhaustion Accident This accident highlights important human factors, competence and regulatory oversight issues.

- UPDATE 25 June 2017: During an air ambulance positioning flight: Impromptu Flypast Leads to Disaster

- UPDATE 13 June 2020: Visual Illusions, a Non Standard Approach and Cockpit Gradient: Business Jet Accident at Aarhus

UPDATE 22 June 2017: A Canadian Parliament Committee issued a report to the federal government with 17 recommendations, aimed at enhancing aviation safety in Canada. The Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities heard 47 witnesses and received 11 briefs, leading to a report with 17 safety recommendations. These included:

- That the implementation of a Safety Management System becomes mandatory for all commercial operators, including the air taxi sector.

- That Transport Canada:

a. establish targets to ensure more on-site safety inspections versus Safety Management System audits;

b. use poor results from Safety Management System audits (including whistleblower input) as a ‘flag’ for prioritizing on-site inspections;

c. Review whistleblower policies to ensure adequate protection for people who raise safety issues to foster open, transparent and timely disclosure of safety concerns. - That the government make sure that Safety Management Systems are accompanied by an effective, properly financed, adequately staffed system of regulatory oversight: monitoring, surveillance and enforcement supported by sufficient, appropriately trained staff.

- That Transport Canada review all training processes and training materials for civil aviation inspectors to ensure they have the resources to perform their duties effectively.

UPDATE 17 July 2017: TSB CRM/ADM recommendation stemming from 1998 airplane crash ‘still active’

UPDATE 8 July 2018: Distracted B1900C Wheels Up Landing in the Bahamas

UPDATE 16 May 2019: Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns

UPDATE 20 May 2019: Regulatory oversight of New Zealand helicopter operators was challenged after a 2015 accident.

UPDATE 1 September 2019: King Air 100 Stalls on Take Off After Exposed to 14 Minutes of Snowfall: No De-Icing Applied

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. We will be presenting for the second year running. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Recent Comments