Inadvertent Entry into IMC During Mountaintop HESLO (Air Greenland Airbus AS350B3 OY-HGT)

On 24 June 2019, during Helicopter External Sling Load Operation (HESLO) in Greenland inadvertent entry to Instrument Metrological Conditions (IMC) resulted in Air Greenland Airbus AS350B3 OY-HGT impacting the ground. The pilot escaped injury.

The Accident

The Accident Investigation Board Denmark (AIBD) explain in their safety investigation report that the helicopter was moving fuel with a 30 m long line from a barge to the mountaintop Telesite Dye One communication site. This waa at a former Distant Early Warning Line radar site at 4757 feet AMSL on Qaqatoqaq, near Sisimiut (formerly Holsteinsborg).

The pilot recalled the wind was 210°, 5 knots, no turbulence and there were fog and cloud in the vicinity of the telecoms site.

Telesite Dye One Communication Site at 4757 feet AMSL on Qaqatoqaq near Sisimiut, Greenland (Credit: via AIB Denmark)

The pilot was 36, had flown 3037 hours in total and had “extensive firefighting and mountain flying experience”, including operating with longlines. The pilot was on a short term contract and completed their last Operator Proficiency Check (OPC) 4 months before, which included demonstrating a whiteout landing. They had also completed the operator’s HESLO check in March and had been observed for 2 days in line flying under supervision.

The pilot had already successfully made 28 of the 30 planned movements of what appear to be 1000 litre IBCs, and the pilot had discussed with a Task Specialist (TS) at the barge the possibility of doing a second tasking before sunset.

Airbus AS350B3 OY-HGT Making an Earlier HESLO Delivery at Dye One That Day (Credit: Air Greenland via AIB Denmark)

On the 29th lift, the helicopter started to climb, and…

…at approximately 400-600 feet above the ground, along the mountain ridge and passing approximately 2200 feet Mean Sea Level (MSL), the pilot called a TS at the telesite station in order to obtain an opinion on the visibility and presence of clouds at the mountaintop. The TS reported that “actually only the telesite station itself was open, but the rest was foggy”. The pilot replied that he would “try to find his way up to the mountaintop”.

After several turns during climb and at various airspeeds, the pilot at approximately 4900 feet MSL on a westerly track, approached the agreed-upon delivery point, which was a footbridge along the station buildings.

The pilot was focused on the delivery point, a footbridge along the station buildings, and manoeuvring the helicopter. While not explained, this presumably made filling the site’s fuel tanks easier for workers at the site than if the fuel had been delivered to the lower helipad.

Telesite Dye One Communication Site Greenland: Footbridge in Yellow, Lower Helipad in Red, Three Site Fuel Tanks Between (Credit: via AIB Denmark)

While approximately 150 feet above the ground, due to clouds/fog the pilot lost external visual references and started feeling spatial disorientated. Fearing the fuel tank might hit ground personnel or structure, the pilot “abruptly started flying rearward” intending to release the load.

In combination with various oscillating flight parameters, and an unstable external load, the pilot experienced partial loss of control of the helicopter. After further rearward, descending, oscillating flight, the fuel tank collided with rocky terrain. Approximately 30 m further downhill the pilot successfully released the load using the electrically operated release control on the cyclic stick.

In a helicopter nose down attitude on a southerly track, at a high sink rate, and at a low height above the ground, the pilot regained partial visual references and noted that impact was inevitable. …approximately 100 meters downhill, the helicopter skids impacted with rocky terrain, and the long line entangled with rocks….

The helicopter ended up on its right hand side with the nose section facing towards Telesite Dye One. The pilot felt unharmed and evacuated the helicopter through the left hand door.

Witnesses observing the sequence of events initiated a rescue mission. G-forces activated the onboard Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT).

The helicopter was equipped with an Appareo Vision 1000 on-board data and image recorder. The BEA assisted by downloading data which was “of good quality and useful to the AIB safety investigation”.

Safety Analysis

AIB remark that:

In general, when operating in specific remote and hostile areas, the access to proper and reliable weather information before flight might be difficult or even impossible, which might make the preflight planning phase and the later on operational phase unpredictable and not fact-based leading to subjective decision-making processes. The above statement is an operational condition, when operating in such specific environments, which, in the general opinion of the AIB, requires operational creativity and innovation in order to optimize flight safety.

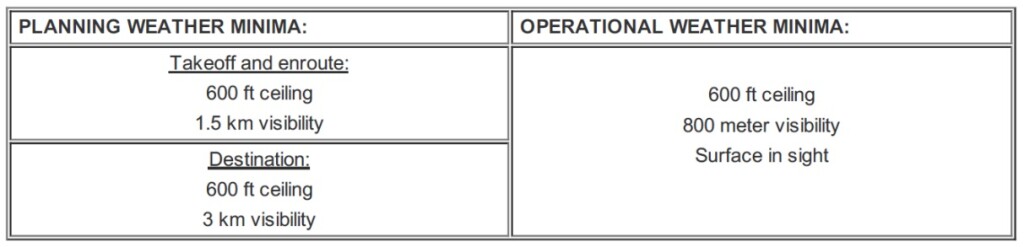

They do note that the operational weather minima in the operator’s Operations Manual Part B was “not fully comparable to the rules of the air (BL 7-1)”.

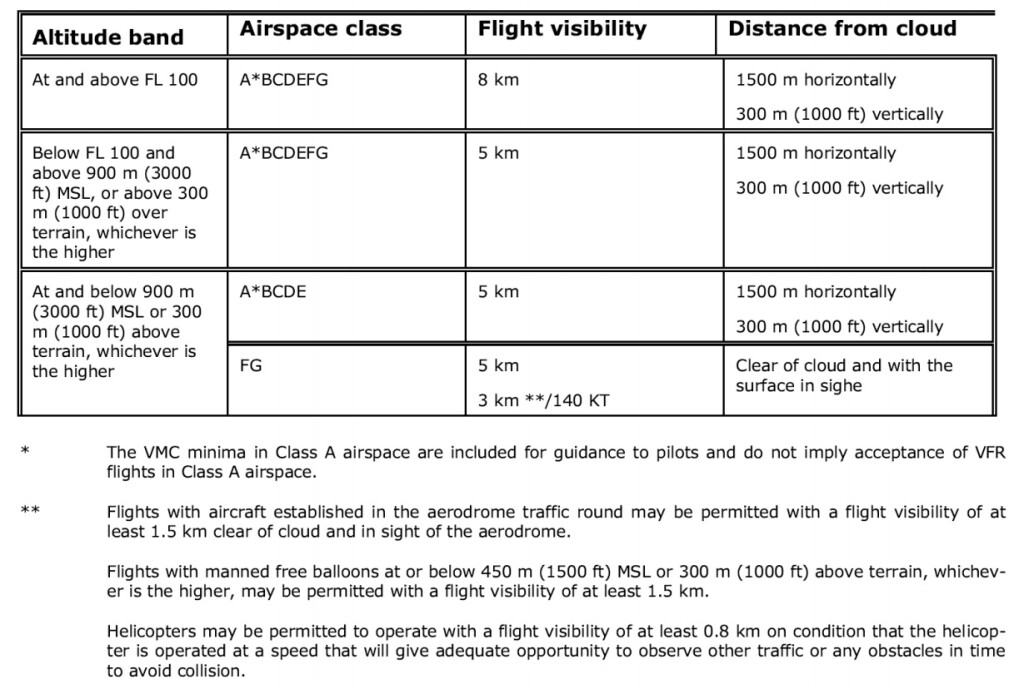

However, to the AIB, the limitation in the standard operating procedures of a cloud ceiling of 600 feet seems to be more restrictive than the wording clear of cloud of BL 7-1 for operations in airspace class G.

The operator categorized HESLO as a high risk SPO (Specialised Operations), seemingly due to the need to conduct the task at low height above ground. AIB comment:

Taking into consideration that the accident flight was a high risk SPO, the AIB, from a flight safety point of view, finds the limitation on cloud ceiling rational.

They observe that:

At the time of the accident, the pilot had performed several sling operations from the fjord to the mountaintop and presumably had a reliable knowledge of the general weather conditions at the mountaintop.

S-turns, instead of a straight route, at various airspeeds during climb in combination with the radio correspondence between the pilot and a TS at Telesite Dye One supports the premise that the weather conditions at the mountaintop were marginal for this sling operation.

The [selection of a delivery point of the] footbridge compared to the helipad required, in the opinion of the AIB, more pilot precision and head down external focus, which in combination with the actual weather conditions at the mountaintop probably reduced and/or eliminated pilot perception of changes to the available external visual cues.

The helicopter, while positioning at the mountaintop, most likely entered orographic clouds causing loss of pilot external visual references.

Upon loosing external visual references, the pilot feared the consequences of an intermediate release of the fuel tank or a fuel tank collision with obstacles and abruptly started flying rearward. This rationale of the pilot potentially prevented a more severe outcome.

Loss of external visual cues leading to spatial disorientation resulted in an emergency requiring release of the external load. The emergency procedure, though not specific for this type of emergency, stipulated release of the external load. However, the emergency procedure did not distinguish between a cargo hook and a main cargo hook release.

AIB are slightly contradictory as (emphasis added)…

In an emergency, the AIB considers a main cargo hook release (release of the external load and the long line) to be more conducive to flight safety than just a cargo hook release [as executed].

However:

The impact of the helicopter skids with rocky terrain at a shallow angle, and the tightening of the long line slowing down the forward energy and reducing the final impact force, made the accident survivable.

Which just goes to show the dilemma drafting procedures and making decisions in an emergency! The investigators opine that in relation to the hook release:

Taking into consideration the previous flying experience of the pilot (firefighting) and the sling operations of the day, the pilot most likely acted on stored routines…when trying to and finally successfully released the fuel tank at the cargo hook.

Further:

A potential launch of another sling operation at another location before sunset might have provoked a pilot self-induced commercial pressure and task fixation. Task fixation might have expanded the pilot risk tolerances leading to changes of perception of risks, and decision-making processes during the sling operation.

AIB Conclusions

The helicopter, while positioning for the agreed-upon delivery point, entered orographic clouds causing loss of pilot external visual references.

While attempting to recover, loss of external visual cues led to spatial disorientation and a partial loss of control of the helicopter.

Safety Resources

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

- EC120 Underslung Load Accident 26 September 2013 – Report

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Unexpected Load: B407 USL / External Cargo Accident in PNG

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable

- Fallacy of ‘Training Out’ Error: Japanese AS332L1 Dropped Load

- Helicopter External Sling Load Operation Occurrences in New Zealand

- Maintenance Issues in Fire-Fighting S-61A Accident

- HESLO AS350B2 Dropped Load – Phase Out of Spring-Loaded Keepers for Keeperless Hooks

- Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- An AW109SP, Overweight VIPs and Crew Stress

- Low Viz Helicopter CFIT Accident, Alaska

- Alaskan AS350 CFIT With Unrestrained Cargo in Cabin

- Beware Last Minute Changes in Plan

- Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++

- AS365N3 9M-IGB Fatal Accident

- AW139 Brownout Accident with the Nigerian VP Aboard

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- Offshore Helicopter Accident Ghana 8 May 2014 & The Importance of Emergency Response

- BFU Investigate S-76B Descending to 20ft at 40 kts En Route in Poor Visibility

- Impromptu Landing – Unseen Cable

- UPDATE 7 September 2020: Shocking Accident: Two Workers Electrocuted During HESLO

- UPDATE 31 October 2020: Loss of Control During HESLO Construction Task: BEA Highlight Wellbeing / Personal Readiness

- UPDATE 2 April 2021: Windscreen Rain Refraction: Mountain Mine Site HESLO CFIT

- UPDATE 24 April 2021: Unballasted Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel (HESLO in France)

- UPDATE 12 June 2021: HESLO Dynamic Rollover in Alaska

- UPDATE 28 August 2021: Ditching after Blade Strike During HESLO from a Ship

- UPDATE 4 September 2021: Dynamic Rollover During HESLO at Gusty Mountain Site

- UPDATE 1 January 2022: Snagged Sling Line Pulled into Main Rotor During HESLO Shutdown

- UPDATE 19 November 2022: Whiteout During Avalanche Explosive Placement

- UPDATE 18 March 2023: HESLO AS350 Fatal Accident Positioning with an Unloaded Long Line

- UPDATE 5 August 2023: A Concrete Case of Commercial Pressure: Fatal Swiss HESLO Accident

Also:

- The Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) run Helicopter External Load Operations for Ground Personnel training.

- See also UK CAA CAP 426 – Helicopter External Load Operations

Recent Comments