NTSB Report on Miami Air International Jacksonville Boeing 737-800 N732MA Runway Excursion

On 3 May 2019 Boeing 737-81Q (WL) N732MA of Miami Air International suffered a nighttime runway excursion on landing in a thunderstorm at Jacksonville Naval Air Station, Florida. The aircraft, which was conducting a charter flight for the US DoD, came to rest in the St. Johns River. Only 1 minor injury occurred to the 143 occupants.

Boeing 737-81Q (WL) N732MA of Miami Air International after Runway Excursion at Jacksonville NAS, FL (Credit: NTSB)

The Accident Flight

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) explain in their safety investigation report, published on 4 August 2021, that the takeoff from Guantánamo NAS, Cuba, climb and cruise had been uneventful.

The No. 1 (left) thrust reverser was inoperative and was deferred in accordance with the Minimum Equipment List (MEL) as a Category C item.

The aircraft commander (aged 55, with 7500 hours total flying time, 2204 on type) was the pilot flying. The co-pilot (aged 47, also with 7500 hours total flying time, but mostly in light aircraft, and only 18 hours on type) was the pilot monitoring. The aircraft commander was also performing check airman duties as the co-pilot was in the process of completing operating experience training.

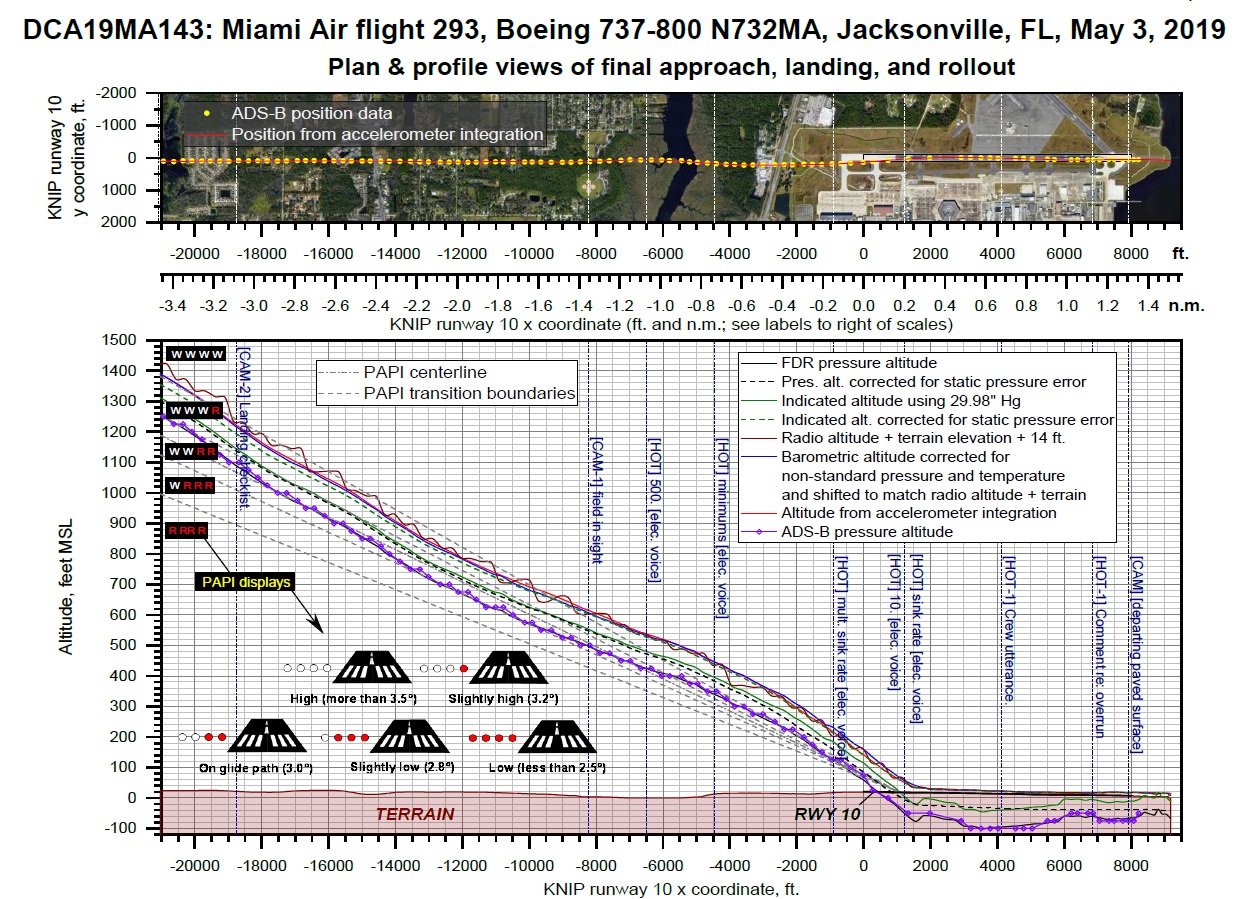

During the approach to Jacksonville NAS, the flight crew had two runway change discussions with air traffic controllers due to reported weather conditions (moderate to heavy precipitation) near the field; the pilots ultimately executed the area navigation GPS approach to runway 10, which was ungrooved and had a displaced threshold 997 ft from the threshold, leaving an available landing distance of 8,006 ft.

As the airplane descended through 1,390 ft mean sea level (msl), the pilots configured it for landing with the flaps set at 30º and the landing gear extended; however, the speedbrake handle was not placed in the armed position as specified in the Landing checklist. At an altitude of about 1,100 ft msl and 2.8 nm from the runway, the airplane was slightly above the glidepath, and its airspeed was on target. Over the next minute, the indicated airspeed increased to 170 knots (17 knots above the target approach speed), and groundspeed reached 180 knots, including an estimated 7-knot tailwind.

At an altitude of about 680 ft msl and 1.6 nm from the threshold, the airplane deviated further above the 3° glidepath such that the precision approach path indicator (PAPI) lights would have appeared to the flight crew as four white lights and would retain that appearance throughout the rest of the approach. Eight seconds before touchdown, multiple enhanced ground proximity warning system alerts announced “sink rate” as the airplane’s descent rate peaked at 1,580 fpm. The airplane crossed the displaced threshold 120 ft above the runway (the PAPI glidepath crosses the displaced threshold about 54 ft above the runway) and 17 knots above the target approach speed, with a groundspeed of 180 knots and a rate of descent about 1,450 ft per minute (fpm). The airplane touched down about 1,580 ft beyond the displaced threshold, which was 80 ft beyond the designated touchdown zone as specified in the operator’s standard operating procedures (SOP).

Between 2138 and 2139, about 4 minutes before [touchdown] the 1-minute recorded rainfall rate was as high as 2.4 inches per hour. At 2141, about 1 minute before the accident, the 1-minute rainfall rate was 1.2 inches per hour; it decreased to 0.6 inch per hour at 2142 then increased to 1.8 inch per hour at 2143. The rainfall rate…and the macrotexture depth and cross-slope of runway 10 could have produced water depths on portions of the runway close to or exceeding the 3-mm (1/8-inch) depth considered to be a flooded condition.

After touchdown, the captain deployed the No. 2 engine thrust reverser and began braking; he later reported, however, that he did not feel the aircraft decelerate and increased the brake pressure. The speedbrakes deployed about 4 seconds after touchdown, most likely triggered by the movement of the right throttle into the idle reverse thrust detent after main gear tire spinup. The automatic deployment of the speedbrakes was likely delayed by about 3 seconds compared to the automatic deployment that could have been obtained by arming the speedbrakes before landing.

As the airplane travelled down the runway, drifting back and forth from the centerline, it developed a drift angle as high as 8° (the drift angle is the difference between the airplane’s track over the ground and its heading). This drift angle developed a cornering force on the main gear tires, which helped the airplane correct back to the centerline; however, the cornering demand on the tires likely reduced the tire braking friction available to slow the airplane.

The airplane crossed the end of the runway about 55 ft right of the centerline and impacted a seawall 90 ft to the right of the centerline, 9,170 ft beyond the displaced threshold, and 1,164 ft beyond the departure end of runway 10.

The Emergency Evacuation

After the aircraft came to rest the crew began an emergency evacuation.

Boeing 737-81Q (WL) N732MA of Miami Air International after Runway Excursion at Jacksonville NAS, FL (Ctedit: NTSB)

This proved problematic.

The forward flight attendant seated on the left side of the airplane opened the forward left door (1L), and the slide inflated then twisted. The flight attendant could not detach the slide from the airplane, so she moved to open the forward right door (1R); after opening the door, the 1R slide inflated then began to deflate.

Boeing 737-81Q (WL) N732MA of Miami Air International after Runway Excursion at Jacksonville NAS, FL with 1R Slide Partially Inflated (Ctedit: via NTSB)

The 1R slide deflated as it tore. On examination, nonconformities were found with how the 1R slide had been packed. The failure of the 1L slide was not determined.

The 1L flight attendant attempted to launch a life raft from the 1R door, but it also deflated (the 1R flight attendant was holding passengers back during this time).

Subsequent examination determined that the two inflation houses had not been connected to the raft. The slides and rafts has been maintained at the same overhaul facility in Miami, American Southeast Inflatables and Oxygen Inc (see ‘Footnotes’ below)

As a result, the 1L flight attendant then redirected passengers to the overwing exits.

The flight attendants in the rear of the airplane realized the airplane was in water after landing; they blocked the rear exits (2L and 2R) and instructed the passengers to put on their life vests and move toward the overwing exits for evacuation. Passengers had opened the two overwing exits and some were already standing on the wing. Two life rafts were retrieved from the midcabin ceiling compartment; the flight attendants inflated the life rafts and deployed them off the trailing edges of both wings. Passengers were loaded onto the rafts and, once they were full, the flight attendants unhooked the lines and released them to firefighters who were standing in the water. These two rafts were shuttled back and forth to the shore with passengers onboard.

A fourth raft was retrieved and launched from the right overwing exit. This life raft began to deflate after passengers were in the raft; however, passengers were able to paddle the raft to shore (with the assistance of two passengers who jumped in the water and pushed the raft to shore). A rescue boat arrived and transported six remaining passengers to the shore while the captain, mechanic [who had been in the jumpseat], and the 2R flight attendant conducted a final cabin check to ensure all passengers had evacuated. They were subsequently transported to shore by a rescue boat.

Salvage of Boeing 737-81Q (WL) N732MA of Miami Air International after Runway Excursion at Jacksonville NAS, FL (Ctedit: NTSB)

NTSB Safety Analysis

The NTSB say:

The tailwind, the airplane’s excessive approach speed, and delayed speedbrake deployment increased the energy with which the airplane departed the runway and impacted the seawall, which contributed to the severity of the accident.

Postaccident landing performance calculations revealed that even if the airplane had landed on target speed within the operator’s specified touchdown zone, it would not have been able to stop before reaching the end of the paved runway surface due to the presence of standing water (with depths close to that defined as a flooded condition) on portions of the runway and the resulting viscous hydroplaning. Viscous hydroplaning is associated with the buildup of water pressure under the tire due to viscosity in a thin film of water between a portion of the tire footprint and the runway surface.

The maximum wheel braking friction coefficient developed by the airplane during the landing ground roll was significantly less than the maximum wheel braking friction coefficient underlying the wet runway landing distances published in the airplane manufacturer’s flight crew operating manual (FCOM), computed by the operator’s onboard performance tool (OPT) application, and described in standards and models concerning landing performance in wet runway conditions. Conversely, had the airplane achieved the good braking action associated with a wet (but not flooded) runway published in the FCOM, it would have stopped on the runway even with the approach speed recorded before the accident landing, a 10-knot tailwind, and delayed speedbrake deployment.

No braking action reports were provided to or requested by the accident flight crew, the flight crew briefed using autobrakes rather than maximum manual braking, and the last wind report provided to the flight crew (240° heading at 10 knots) suggested that an estimated 7-knot tailwind component existed during the landing on runway 10.

These considerations should have prompted the flight crew to perform updated landing performance calculations. However, had they done so, they still would have likely determined that the landing distance available on runway 10 was sufficient, under the conditions at the time, if they assumed good braking action (in the absence of reports indicating otherwise) and a merely wet (rather than flooded) runway condition.

NTSB comment that Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) 15009 (issued in November 2015 and current at the time of the accident)…

…suggested that operators take appropriate action to address landing performance on wet runways such as “assuming a braking action of medium or fair when computing time-of-arrival landing performance or increasing the factor applied to the wet runway time-of-arrival landing performance data.” However, similar guidance was not included in the operator’s SOPs at the time of the accident.

Had such guidance been included, the flight crew would have been obligated to assign a surface condition value indicating a condition worse than “good” because the runway was wet, which would have prohibited them from attempting the landing with the tailwind.

Two months after the accident, the FAA issued SAFO 19003, which replaced SAFO 15009, “to further clarify that advisory data for wet runway landings may not provide a safe stopping margin, especially in conditions of moderate or heavy rain on smooth runways”. It recommends that before initiating an approach, pilots verify that the aircraft can stop within the landing distance available, assuming a runway condition of medium-to poor whenever there is the likelihood of either a) moderate or greater rain on a smooth runway or b) heavy rain on a grooved/porous friction course runway.

The NTSB explain that the operator’s SOPs would have prohibited the landing if the surface condition were less than “good”, so identifying if the runway condition was worse was crucial. A “wet” runway was considered to be “good”.

Investigators also highlight that the approach…

…did not meet the operator’s stabilized approach criteria by the time the airplane descended to 1,000 ft agl, and several cues should have led the flight crew to call for a missed approach as required by SOPs.

The airplane’s airspeed exceeded the target approach speed, it was above the glidepath, and its descent rate was greater than 1,000 fpm, which prompted multiple sink rate alerts that should have induced the flight crew to call for a missed approach.

They also however note that the co-pilot’s

…lack of experience flying jet aircraft likely played a role in his inadequate monitoring of the approach (…exemplified by his failure to note, as part of his monitoring duties, that the speedbrake handle had not been armed after calling the item as part of the Landing checklist).

There were also a number of human factors that influence the aircraft commander’s performance:

The captain’s continuation of the [unstabilised] approach….was likely due to a combination of factors. The first was plan continuation bias (an unconscious cognitive bias to continue with the original plan despite changing conditions). The captain’s bias may have been reinforced by a self-induced pressure to land because the flight was late due to an earlier maintenance delay and, the captain and the first officer were approaching the end of their legal duty day. A go-around or diversion to an alternate airport would have caused additional delays.

Another factor was the captain’s increased workload during the approach. Flying and monitoring duties are typically divided to reduce workload for each crewmember. However, cockpit voice recorder data indicate that, rather than relay queries or responses to ATC through the first officer, the captain made multiple radio communications to the approach controller regarding the weather, despite the first officer being responsible for performing this task as part of his monitoring duties.

In addition to performing some of the first officer’s radio duties, the captain was also performing check airman duties in a bad weather situation. Further, the captain’s failure to check that the speedbrake handle was armed, as part of the Landing checklist, was an oversight that was likely another result of his increased workload. Combined with plan continuation bias, the captain’s increased workload from performing additional tasks narrowed his attention and limited his ability to recognize and correctly respond to the cues of an unstabilized approach.

Boeing 737-81Q (WL) N732MA of Miami Air International after Runway Excursion at Jacksonville NAS, FL (Ctedit: NTSB)

NTSB Probable Cause

An extreme loss of braking friction due to heavy rain and the water depth on the ungrooved runway, which resulted in viscous hydroplaning.

Contributing to the accident was the operator’s inadequate guidance for evaluating runway braking conditions and conducting en route landing distance assessments.

Contributing to the continuation of an unstabilized approach were 1) the captain’s plan continuation bias and increased workload due to the weather and performing check airman duties and 2) the first officer’s lack of experience.

Footnotes

On 24 March 2020, Miami Air International filed for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy protection and ceased operations on 8 May 2020.

On 16 October 2020, the FAA announced they had proposed a $464,300 civil penalty against American Southeast Inflatables and Oxygen Inc:

The FAA alleges that between June 2018 and January 2019, the Miami-based company performed unauthorized and improper maintenance on two evacuation slides and one safety raft and installed them on a Boeing 737. All three pieces of equipment failed to work properly when the crew deployed them after the aircraft overran the end of the runway at Jacksonville NAS and came to rest in the St. Johns River on May 3, 2019.

The FAA also alleges that American Southeast performed unauthorized maintenance on an additional 41 emergency evacuation slides between December 2017 and May 2019. Furthermore, the FAA alleges the company failed to have a sufficient number of employees with proper training and expertise to ensure maintenance was performed according to FAA regulations.

The company had 30 days to respond to the FAA.

Safety Resources

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- ATR 72 Rudder Travel Limitation Unit Incident: Latent Potential for Misassembly Meets Commercial Pressure

- BEA Point to Inadequate Maintenance Data and Possible Non-Conforming Fasteners in ATR 42 Door Loss

- B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices

- ERJ-190 Flying Control Rigging Error

- Luftwaffe VVIP Global 5000 Written Off After Flying Control Assembly Error

- C-130 Fireball Due to Modification Error

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors

- NTSB Confirms United Airlines Maintenance Error After 12 Years

- British Midland Boeing 737-400 G-OBME Fatal Accident, Kegworth 8 January 1989

- AAIB: Human Factors and the Identification of Saab 2000 Flight Control Malfunctions

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- Improvised Troubleshooting After Cascading A330 Avionics Problems

- Challenge Assumptions: ATSB on A330 with a u/s GPS

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Confusion of Compelling, But Erroneous, PC-12 Synthetic Vision Display

- C-130J Control Restriction Accident, Jalalabad

- B777 in Autoland Mode Left Runway When Another Aircraft Interfered With the Localiser Signal

- Distracted B1900C Wheels Up Landing in the Bahamas

- HF Lessons from an AS365N3+ Gear Up Landing

- B737 Speed Decay, Automation and Distraction

- Aborted Take Off with Brakes Partially On Results in Runway Excursion

- Easyjet A320 Flap / Landing Gear Mis-selections

- Wrong Engine Shutdown Crash: But You Won’t Guess Which!: BUA BAC One-Eleven G-ASJJ 14 January 1969

- Premature A319 Evacuation With Engines Running

- Runaway Dash 8 Q400 at Aberdeen after Miscommunication Over Chocks

- Misted Masks: AAIB A319 Report Reveals Oxygen Mask Lessons

- Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- ANSV Highlight Procedures & HF After ATR72 Landing Accident

- Safety Lessons from TransAsia ATR-72 Flight GE222 CFIT

- Unalaska Saab 2000 Fatal Runway Excursion: PenAir N686PA 17 Oct 2019

- Cockpit Tensions and an Automated CFIT Accident

- Southwest Unstabilised Approach Accident

- Gust Lock Gaff: King Air A90 Runway Excursion

- A Saab 2000 Descended 900 ft Too Low on Approach to Billund

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- Fatal 2019 DC-3 Turbo Prop Accident, Positioning for FAA Flight Test: Power Loss Plus Failure to Feather

Aerossurance has extensive air safety, operations, SAR, airworthiness, human factors, aviation regulation and safety analysis experience. For practical aviation advice you can trust, contact us at: enquiries@aerossurance.com

Follow us on LinkedIn and on Twitter @Aerossurance for our latest updates.

Recent Comments