Automation Issues During Night SAR Training – Near CFIT (Babcock Galicia Coast Guard Sikorsky S-76C+)

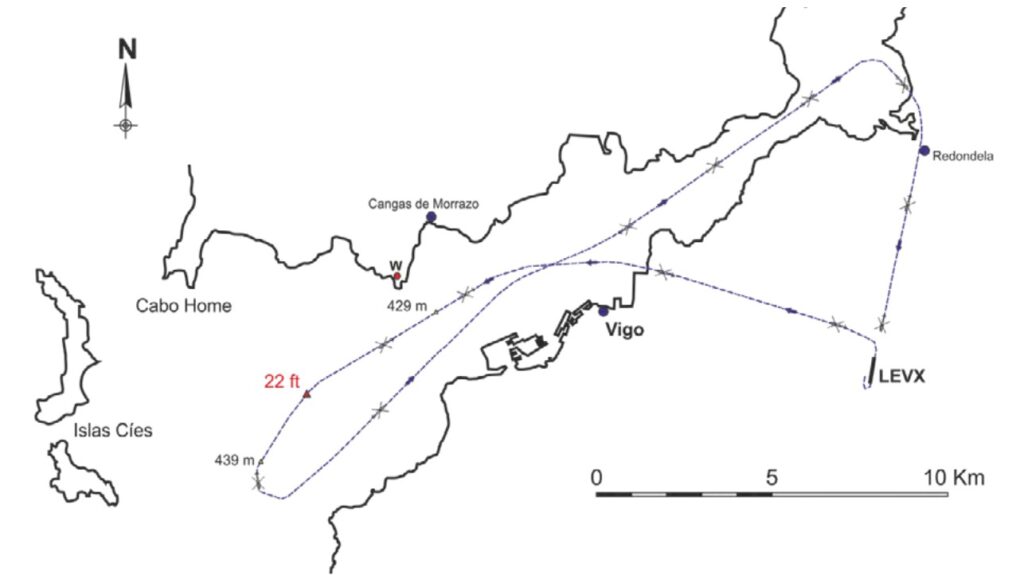

On 26 July 2019 Sikorsky S-76C+ Search and Rescue (SAR) helicopter EC-JES of Babcock España, an entity Babcock has since entered an agreement to sell, inadvertently descended to 22 ft above sea level during a night training exercise over the Vigo estuary in Galicia, Spain near Cabo Home.

Babcock Spain, Galicia Coast Guard SAR Sikorsky S-76C+ (Credit: Contando Estrelas CC BY-SA 2.0)

In the resulting safety investigation by the Spanish the Civil Aviation Accident and Incident Investigation Commission (CIAIAC) the investigators explain that the SAR crew had reported for duty at 22:00 Local Time.

The helicopter took off from Vigo Airport [at 23:10], with a pilot, co-pilot, rescue swimmer, winch operator and instructor on board. In addition to being a training exercise, the winch operator was to undergo a SAR verification during the flight. This would involve a simulated rescue in the vicinity of a cliff.

Cabo Home was a common location for training exercises. This training task had been attempted the day before but been called off due to fog.

The helicopter was contracted to Galician Regional Government’s regional Coast Guard Service, which has helicopters at Vigo and Celeiro. It was being operated under a Certificado de Operador Aéreo Especial (COE), a Special Air Operator Certificate. The Spanish regulator AESA, has issued around 20 COEs to operators performing tasks outside the EASA Basic Regulation, such as SAR, aerial firefighting etc.

At take off the Aircraft Commander or ‘PIC’ (5,170 hours total experience, 1,583 on type) was Pilot Monitoring but took over as Pilot Flying prior to reaching waypoint W (see below).

Winds were light and wave height <2 m. There was little moonlight as:

Winds were light and wave height <2 m. There was little moonlight as:

The moon was in an advanced last quarter phase, four nights before the new moon.

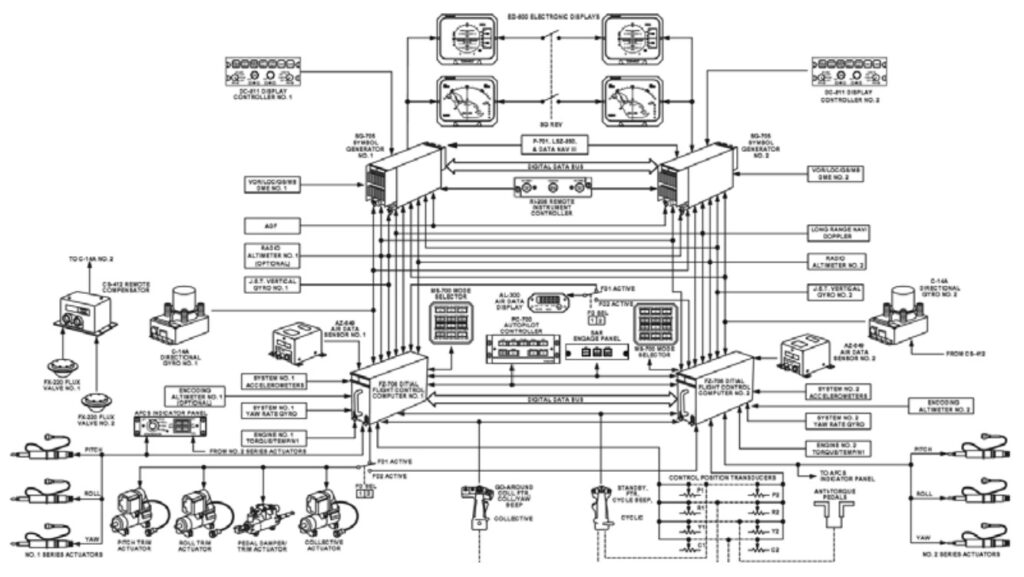

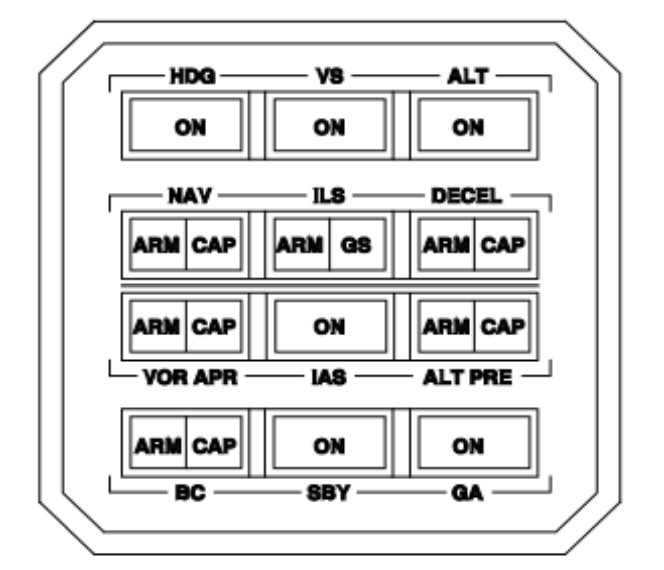

This S-76C+ was equipped with a Honeywell SPZ-7600 Digital Automatic Flight Control System (DAFCS).

The system is coupled to the three axes (pitch, roll and yaw, as well as the collective), and performs the functions of autopilot and flight director. It also incorporates additional functions that reduce the pilot’s workload: automatic trim, heading hold, coordinated turns and automatic levelling.

The Aircraft Commander…

….engaged the IAS, NAV (navigation towards the mouth of the estuary) and ALT (over 1900 ft) modes.

Meanwhile the Co-Pilot (4,806 hours total experience, but only 76 hours on type) was in radio contact with the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) and ATC.

Analysis of the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) confirmed that:

As the crew entered data into the FMS (Flight Management System), the commander explained the process to the co-pilot. The commander can be heard telling the co-pilot that he is activating ALT PRE and VS to descend to 500 ft. The information is copied by the co-pilot. The commander also indicates that he is reducing speed to 80 knots.

CIAIAC explain further that:

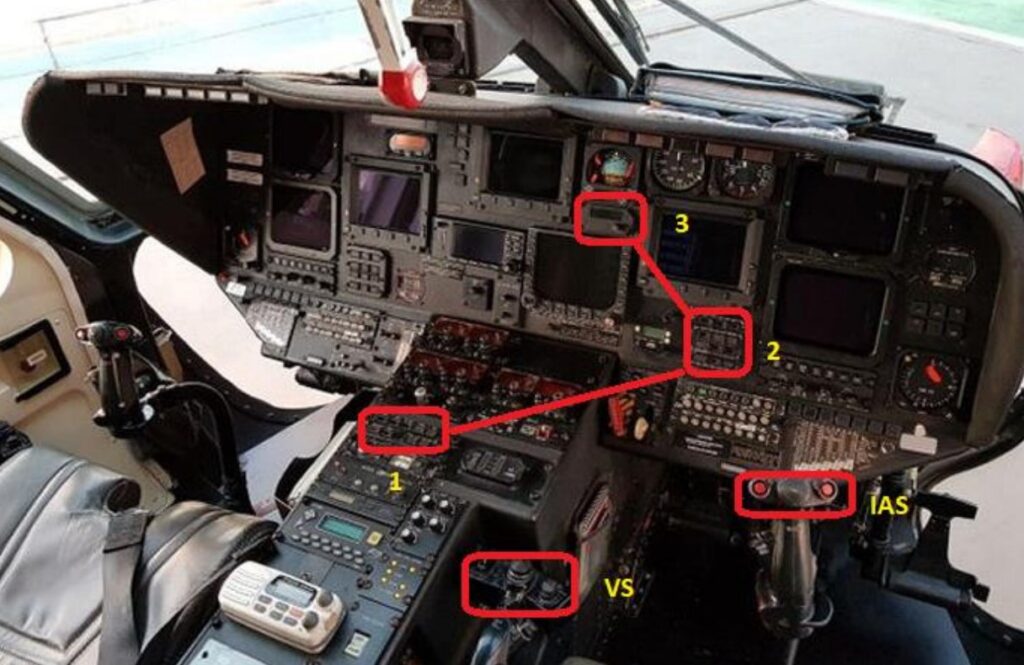

With regard to the use of the SPZ-7600 system controls, pilots initially select the ATT and FD1/2 modes on the PC-700 (1), then select several FD modes on the MS-700 (2).

Before the descent, they select 500 ft of altitude on the AL-300 (3) to descend and maintain that height over the estuary, followed by the ALT PRE Mode on the MS-700 (2) and the desired descent rate of 800 ft followed by V/ S mode on the MS-700 (2). The VS figures and altitude are programmed into the AL-300 from the collective control lever.

Subsequently:

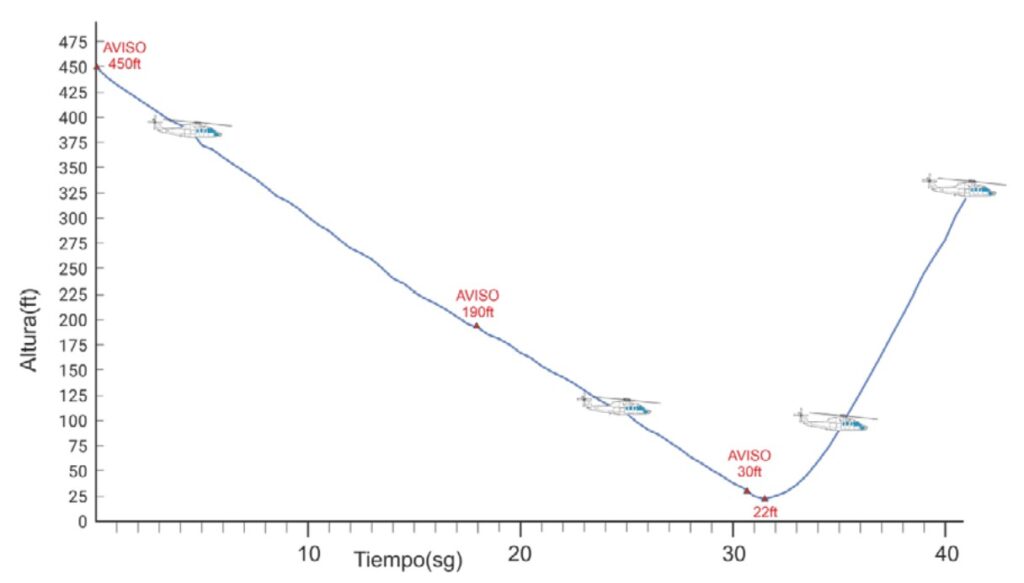

Realising that the helicopter was still too high as it approached the position specified for the night-time cliff exercise, the PIC manoeuvred the aircraft to keep heading over the estuary, passing the Cíes Islands to the right and creating more time to descend.

During the descent, at 1300 ft of altitude, the winch operator [sitting in the front right cabin seat] saw a sailing boat in the estuary entrance channel with the FLIR [Forward Looking Infra Red turret].

Shortly after, the rescue swimmer, sat in the left rear cabin seat, sought confirmation about the descent. The flight crew confirmed they were descending to 500 ft.

Immediately afterwards, the winch operator saw the sailing boat again, this time through the left cabin door window.

…the helicopter was slightly above the boat’s mainsail mast-head light. According to his testimony, he then turned his head to take note of references through his window (rear right-hand side) and in the darkness of the night saw what looked like the surface of the sea.

Glancing back to the left, the helicopter was now “just below the…mast-head light”.

In that instant, the various members of the rescue crew began to call out [and] the co-pilot exclaimed “50 ft” and put the aircraft into a steep climb by pulling the collective pitch control lever upwards.

The PIC felt the “sudden pull” on the collective pitch control lever and pulled it up as well, noting that the N1 was on red.

The winch operator commented that they may have struck the water.

They climbed to a safe altitude and, once straight and levelled, he asked the co-pilot to relinquish the controls, and they returned to the base.

The co-pilot’s abrupt upward pull on the collective produced a loud clicking sound, which initially led them to think that the helicopter’s belly had touched the water.

Once back in straight and level flight, and after calming down, they verified that the cabin was dry and used the FLIR camera to check there was no damage and the antennas were all still in place.

The helicopter landed safely at Vigo.

With regard to the alarms in the cabin, according to the CVR records, when the co-pilot was trying to contact Santiago Approach, the co-pilot’s DH and the landing-gear up alarms sounded at 450 ft. At 250 ft, the ALT-300 alarm sounded. At 190 ft, the pilot’s DH sounded, and between 30 ft and 70 ft, the RAWS alarm can be heard. In this respect, the pilot stated that “he had reset the 450 ft DH and that he had heard the 190 ft DH”.

For his part, the co-pilot said he only heard the 250 ft alarm corresponding to the ALT-300, and that he does not remember hearing any other alarm; not the landing gear alarm (horn-shaped red light which sounds below 300 ft or 60 kt if the landing gear is up), nor the Decision Height alarm (a gong sound and HSI colour change), or the RAWS (which sounds loudly below 30 ft, although it must be pre-set ON-OFF).

CIAIAC Analysis

During night-time SAR operations, visual references, which are generally used to interpret the aircraft’s position during the approach, can be lost, forcing pilots to rely on available data from cockpit instrumentation. To facilitate the flight task in poor visual conditions, pilots require easy access to critical flight information. Flying VFR, the crew used the flight instrument references in conjunction with external visual references.

No comment is made about the safety benefit of Night Vision Imaging Systems (NVIS).

The investigators postulate that crew work load was high at the time with the cabin preparations and radio calls.

With regard to the use of the AP [autopilot] and FD [flight director] and their different modes, it must be taken into account that whenever an automatically controlled altitude change is made, the VS and ALT-PRE MODES are used simultaneously. This makes it possible to descend or ascend at a constant vertical speed until the predetermined altitude is reached. That altitude will then be maintained until the pilot modifies the conditions.

Caution must be taken to ensure that the different aircraft control modes are activated in the selected FD, which must correspond to the pilot at the controls.

From his testimony the investigators were satisfied that the Aircraft Commander had intended to select the appropriate modes, though:

The FDR data indicates that AP1 and AP2 were selected and that the selected FD corresponded to the commander. The V/S mode was active, among others, but the ALTPRE was not.

Therefore, we can assume that the aircraft had instructions to descend at 800 ft per minute (which is reflected in the constant slope of the corresponding graph) but that it had no instruction to stop at any specific height: This meant that once it reached the 500 ft entered into the ALT-300, it continued to descend without stopping.

Significantly:

In his testimony, the commander himself questioned whether he might have pressed DECEL instead of ALT PRE.

The DECEL button is located next to ALT PRE, and given that it is only associated with ILS interception, its activation would have been inconsequential.

CIAIAC state that:

CIAIAC state that:

This explanation could be consistent with the events that followed.

They note that:

If they had cross-checked and used descent call outs, the different aircraft instruments would have alerted the crew to the situation and progression of the vertical navigation during the descent… Eventually, it was a member of the rescue crew, outside the pilot loop/sequence, who drew attention to the situation.

CIAIAC are surprisingly harsh in suggesting:

…there was general confusion in the cockpit with regard to which alarms sounded, which were reset, and even when they should have sounded: the HD 450 ft co-pilot alarm cannot be reset, especially not by the pilot because he cannot hear it.

They go on to say:

Therefore, this alarm was confused with the landing gear alarm that must be reset and is audible in the cockpit. Furthermore, the co-pilot, who according to his own testimony was not entirely familiar with this helicopter, thought the aforementioned landing gear alarm sounded below 300 ft and not at 450 ft as it does in this specially adapted aircraft.

In any case, mistakenly or not, both crew members heard and noted alarms that warned of positions below the 500 ft altitude supposedly selected in the ALT 300, without either of them realising they were in a compromised situation.

The investigators would have been well advised to have studied a 2018 UK CAA research report that examined terrain warning annunciation and past cases in which alarms were not heard.

CIAIAC Conclusions

CIAIAC say:

We conclude that the crew did not act in accordance with operational procedures because they ignored the cockpit alarms and did not work in a coordinated manner, giving priority to other activities and ultimately failing to monitor the flight, leading to a total loss of situational awareness.

Also:

We are issuing a recommendation to the operator, Babcock, advising them to improve training

on procedural adherence, response to warnings and alarms and, particularly, CFIT prevention during crew training exercises.

Reminder

A public inquiry chaired by Anthony Hidden QC investigated 1988 Clapham Junction rail accident. In the report of the investigation, known as the Hidden Report, he commented:

There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look flawed and less sensible in the misleading light of hindsight. It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. See EHEST Safety Leaflet HE9 Automation and Flight Path Management

HeliOffshore has published a Unexpected Events Pilot Monitoring Research Report using eye-tracking technology.

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Aerossurance Marks RAeS 150th Anniversary by Sponsoring Rotorcraft Automation Conference

- Technology Friend or Foe – Automation in Offshore Helicopter Operation

- Offshore Night Near Miss: Marine Pilot Transfer Unintended Descent

- North Sea Helicopter Struck Sea After Loss of Control on Approach During Night Shuttling (S-76A G-BHYB 1983)

- NTSB Investigation into AW139 Bahamas Night Take Off Accident

- Night Offshore Training AS365N3 Accident in India 2015

- Loss of Control, Twice, by Offshore Helicopter off Nova Scotia

- SAR Helicopter Loss of Control at Night: ATSB Report

- SAR Hoist Cable Snag and Facture, Followed By Release of an Unserviceable Aircraft

- TCM’s Fall from SAR AW139 Doorway While Commencing Night Hoist Training

- Guarding Against a Hoist Cable Cut

- SAR AW139 Dropped Object: Attachment of New Hook Weight

- Swedish SAR AW139 Damaged in Aborted Take-off Training Exercise

- Military SAR H225M Caracal Double Hoist Fatality Accident

- Marine Pilot Transfer Winching Accident: referenced in the Royal College of Art (RCA) & Lloyd’s Register Foundation Safety Grand Challenge: Safe Ship Boarding & Thames Safest River 2030

- Fatal Fall From B429 During Helicopter Hoist Training

- Hoist Assembly Errors: SAR Personnel Dropped Into Sea A UH-60M accident in Taiwan during a SAR exercise.

- USAF Helicopter Hoist Training Accident: equipment snagged on obstacle

- Fall From Stretcher During Taiwanese SAR Mission (NASC AS365N2 NA-104)

- Fatal Taiwanese Night SAR Hoist Mission (NASC AS365N3 NA-106)

- SAR Crew With High Workload Land Wheels Up on Beach

- HEMS S-76C+ Night Approach LOC-I Incident

- Night Offshore Windfarm HEMS Winch Training CFIT (BK117C1 D-HDRJ)

- NH90 Caribbean Loss of Control – Inflight, Water Impact and Survivability Issues

- SAR AW101 Roll-Over: Entry Into Service Involved “Persistently Elevated and Confusing Operational Risk”

- UPDATE 28 December 2022: Night Mountain Rescue Hoist Training Fatal CFIT

- UPDATE 7 January 2023: Blinded by Light, Spanish Customs AS365 Crashed During Night-time Hot Pursuit

- UPDATE 8 July 2023: BK117 Offshore Medevac CFIT & Survivability Issues

- UPDATE 16 July 2023: SAR AW139 LOC-I During Positioning Flight

- UPDATE 13 July 2024: Fatal USCG SAR Training Flight: Inadvertent IMC

The Tender Trap: SAR and Medevac Contract Design Aerossurance’s Andy Evans discusses how to set up clear and robust contracts for effective contracted HEMS operations.

Babcock Spain, Galicia Coast Guard SAR Sikorsky S-76C+ (Credit: Contando Estrelas CC BY-SA 2.0)

Recent Comments