Offshore Night Near Miss: Marine Pilot Transfer Unintended Descent (Le Havre AS365N3 F-GYLH)

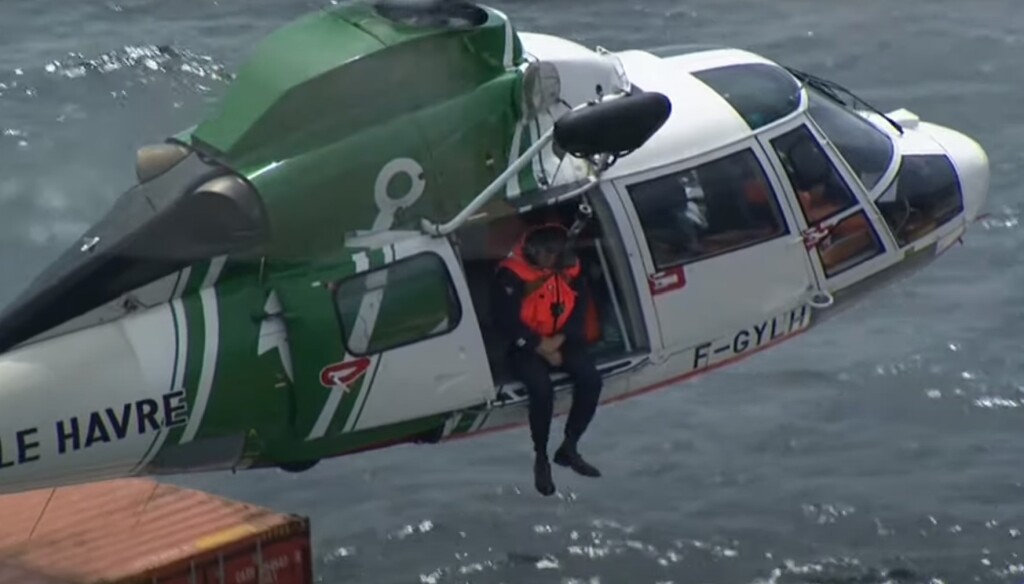

On the night of 11 February 2021 Airbus AS365N3 F-GYLH nearly collided with the surface of the sea off Le Havre during a Marine Pilot Transfer (MPT) flight with 4 people on-board. The BEA (the Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile) issued their safety investigation report (in French only) into this serious incident on 10 February 2022 that highlights issues of automation use in a high workload flight.

Organisational Context

The helicopter was operated by the Le Havre-Fécamp Pilot Station. Dating from the 16th century, that organisation provides pilotage for ships visiting Le Havre, Antifer and Fécamp. They use both launches and their own AS365N3 for marine pilot transfer. They first introduced helicopter in 1976, an Alouette III. They did suffer a fatal accident on 8 September 2005 when their previous AS365N3, F-GYPH, collided with the surface of the sea at night off Cape Antifer. It was manoeuvring to rendezvous with a tanker that has entered a fog bank. In the 2005 accident the contributory factors identified were, the pilots “overconfidence”, “uncorrected behavioural deviations” (such as the pilot not routinely wearing his seat harness) and “a management structure that did not allow sufficient surveillance of the activity to be exercised”. After the 2005 accident procedures for the use of autopilot upper modes were reportedly enhanced and greater emphasis made of crew resource management with the hoist operator.

The Pilot Station is a form of collective, managed by an elected President. The President is the Accountable Manager for the purposes of European Regulation (EU) No. 965/2012. According to the BEA the operation is treated as non-commercial air transport operation under Part-NCC and Part-SPO for the hoisting operations. Although not required by Part-NCC, F-GYLH was equipped with a combined CVFDR (a Honeywell ARCOMBI) as a learning from the 2005 accident.

The Pilot Station employed two helicopter pilots. One was also the Flight Operations Manager and the other the Safety Manager. The aircraft was maintained by two engineers, who were also trained as the hoist operators i.e. Technical Crew Members (TCM). The Head of Compliance Control was a part-time, outsourced role. The BEA do not comment on the management of Flight Training or Continued Airworthiness.

The BEA explain that in 2019, due to a shortage of engineers, four having resigned over two years, flight operations had been paused for a period. The February 2020 annual internal audit had identified…

…a significant decrease, over the 2019 period, in the level of performance of the helicopter department and the aircraft dispatch rate, with numerous machine stoppages for technical and human reasons. At the same time, a significant increase in non-conformities is noticeable in the present audit in contrast to the previous one…

The audit report also highlighted cultural issues between the helicopter department and their parent organisation which created…

…a slow but certain drift of the operational standards of the exploitation, a reduction of the attention during the times of duty, a professional disengagement of the crew members, creates blocking points in the daily operation and fosters a confrontational environment.

The report acknowledged that meetings had been held to attempt to resolve the issues but it was a lingering issue. The issue had been raised during audits by the regulator and in particular the specifics of hoist operator training (topical due to the turnover in engineer / hoist ops). The BEA note that no specific action was taken by the regulator.

The President (and Accountable Manager) however changed in April 2020. The next annual internal audit (in November 2020) stated there was…

…a real improvement in the operator’s performance and a significant reduction in the number of non-compliances… More importantly, the change of Accountable Manager…was an opportunity, a new impetus, renewing with a culture of listening and taking into account the technical team. The risks identified the previous year, mainly related to tensions between the technical team and the executive, are, for the most part, in the process of self-mitigation due to the return of collaboration between the two parties.

The BEA however note that “certain social difficulties continued” in particular that the engineers recruited had no prior hoisting experience. The Flight Operations Manager also expressed concern over this to the BEA.

The Serious Incident Flight

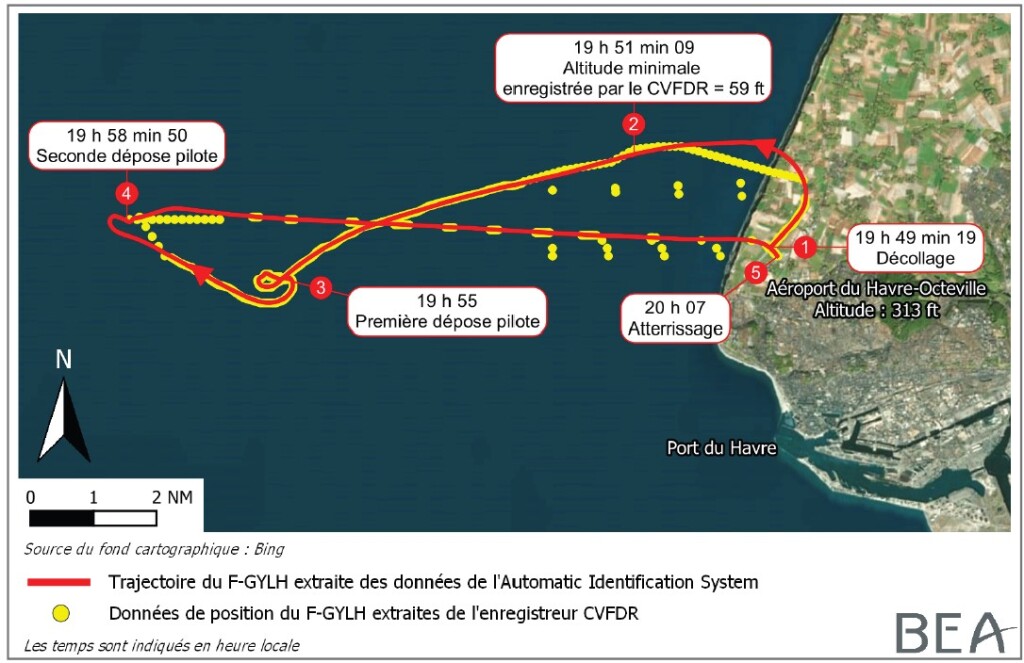

The helicopter departed Le Havre-Octeville airport for a night VFR flight at 19:49:19 Local Time (civil twilight ended just over an hour earlier, there was a new moon and altocumulus at 10000 ft). On board were a single pilot, a hoist operator sat in a central seat in the cabin and two marine pilots sat in the rear row of cabin seats. The marine pilots were destined for two oil tankers approaching Le Havre.

The pilot on this flight was the Flight Operations Manager. He was 59, had started his career in the military and had flown for the Pilot Station since 2000 (the same year the pilot in the 2005 accident joined). He had 6650 hours of experience (including 16700 hoist cycles), 5250 hours on type an 1802 hours at night. The hoist operator was a Part-66 licenced engineer recruited in March 2020 with no prior hoist operator experience. He had been trained by his predecessor but expressed concern to the BEA that he was now also expected to train the next new recruit from scratch. At the time he had 112 hours of experience, all on the AS365N3, 50 at night, with about 600 hoist cycles in that time.

The METAR for Le Havre-Octeville at 19:30 was: LFOH 111830Z AUTO 10015KT CAVOK M00/M08 Q1023 TEMPO 10017G27KT

Shortly after take-off the helicopter pilot made a radio call that “we take off in 04, climb 700 ft, left turn heading 270, distance for 10 nautical miles”. Then at 19:49:42, passing through 760 ft, the ‘HDG’ heading tracking autopilot upper mode was engaged and the helicopter turned left towards the heading 270° that had been selected by the pilot.

Crucially the pilot thought he had simultaneously also engaged the ‘ALT’ altitude hold mode, which was not the case. The BEA observe that the Operations Manual (OM) states:

The use of the higher modes is a valuable aid to piloting, particularly in IMC, degraded or night conditions. However, special attention must be paid to their management in order to avoid confusion of use between the two modes or forgetting during a critical phase of flight.

It is also a requirement in OM Part A 8.3 in cruise that the pilot verbalise the mode selection and the hoist operator then verbally confirms they have checked the selected modes. However, the crews explained to the BEA that in practice OM B Checklists were used and these did not include that check, because the cruise phase was so short in their normal operations that cruise checks were omitted The BEA also noted that the checklists were used as to-do lists, memorised by the hoist operators, rather than used as a challenge and response tool.

Without the ALT mode being engaged, the helicopter began to descend during the turn, a descent that was not sensed by the helicopter pilot. The helicopter pilot recalls seeing neither the coastline or any lights on the surface but commented to the BEA that “at night, he flies on instruments, his head in the cockpit most of the time, without looking outside”.

At 19:49:55 (just 36 seconds after take off), the helicopter pilot contacted the radio operator of first tanker and a dialogue ensued concerning the position and heading of tanker and helicopter, lasting about a minute. The hoist operator was focused on the position of the tanker too, looking at a display of maritime Automatic Identification System (AIS) data and the weather radar display.

The hoist operator also discussed the vessel position with the helicopter pilot at this time.

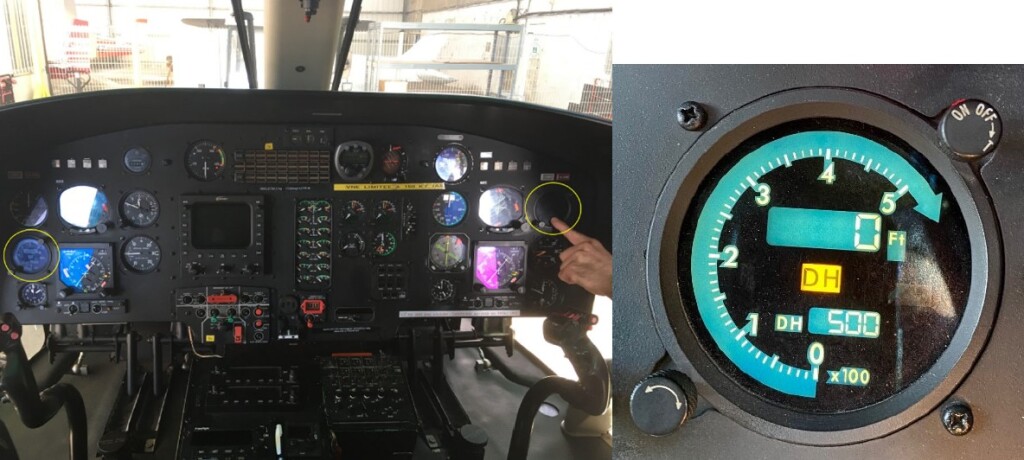

The operator’s procedure was that at night a Decision Height of 500 ft would be set on the right hand RADALT and 300 ft on the left hand RADALT (both would be 300 ft in the day).

RADALT Positions & DH Indication – Pilot Station Le Havre – Fécamp Airbus AS365N3 F-GYLH (Credit: BEA)

At 19:50:36 the helicopter descended through 500 ft. This triggered an aural tone and a yellow light on the right hand RADALT. These indications occurred during the dialogue about vessel position and were missed by the helicopter pilot.

At 19:50:52 the helicopter descended through 300 ft, indicating the descent rate was now c740 ft/min, triggering the left hand RADALT. Again the aural tone coincided with radio communication and the yellow light is even more difficult for to see on a RADALT mounted across the instrument panel from the pilot.

Fifteen seconds later one of the marine pilots commented on the intercom “we’re really low now”. The hoist operator agreed “Yeah we’re… we’re super low huh”. Coincidentally the helicopter pilot then initiated a recovery. He applied a pitch-up attitude of 5°, maintaining power and a zero bank angle.

The lowest height recorded was 59 ft (although the investigators note the Honeywell recorder had suffered numerous data recording interruptions) and the speed had reached 158 knots (8 knots above VNE [velocity never exceed]). The VNE was lowered in 2008 by EASA Airworthiness Directive AD 2008-0204 after reports of horizontal stabiliser fractures on AS365N3 due to vibration at high speed. This limit could be raised on embodiment of Service Bulletin AS365-55.00.06, but this was not fitted to F-GYLH.

Perhaps surprisingly, the flight continued and the marine pilots were hoisted at 19:55 to the first ship after an Airborne Radar Approach (ARA) and 19:58:50 after a visual approach to the second tanker, before landing back at Le Havre-Octeville at 20:07.

Contributing Factors Identified by BEA

The BEA summarised this as a “short, routine single-pilot flight on a complex aircraft…during a dark night” and concluded the following factors contributed to the near collision with the surface of the water:

- The lack of monitoring of flight parameters such as altitude, speed and the autopilot modes engaged, which can be explained in particular by the workload experienced by the helicopter pilot and hoist operator in this very short flight phase.

- The non-perception by the helicopter pilot and hoist operator of the audio and visual indications of the radio altimeters warning of approaching the ground which can be explained in particular by the low salience, both audio and visual, of the indications of the radio-altimeters. decision height (DH) crossing altimeters.

- Inaccuracies and contradictions in the Operational Manual procedures, for example not making it mandatory to engage ALT mode during cruises in night or IFR flight and not requiring the completion of a checklist in this very short flight phase.

- The non-application of the Operational Manual procedure requiring in particular the announcement by the pilot and the verification by the hoist operators of the autopilot upper modes engaged. This non-application of the procedures can be explained in particular by an insufficient adequacy of the written flight procedures in relation to the reality of the operation.

- Operational ab initio training of hoist operators that allowed a low tolerance for errors and omissions in a single-pilot situation.

Safety Actions Taken

Some of the organisational factors had been identified in advance, but by the time of the accident had only been partly addressed. Since the serious incident occurred the following actions had been taken:

- The overhaul of flight procedures and associated checklists, particularly with regard to the use of the autopilot upper modes.

- Simplification and revision of OM A with regard to flight procedures and revisions to OM B checklists.

- Introduction of a cruise checklist for night and IFR flights to be completed after take-off and before the first contact with the ships then after the last ship contact and before returning to the aerodrome, with the following items: RADAR: ON and SUP MODES: ALT + HDG

- Introduction and systematic application of the principle of call-outs for checklists where in particular the actions of display and change of mode of the autopilot are announced by the pilot in command and are the subject of verification and read-back by the hoist operators

- The implementation of a new initial training for hoist operators with Initial TCM and hoist training outsourced to specialist organizations.

- Recruitment of a new hoist operator with hoist experience.

- The study on how to make the sound indication of the radio altimeters more prominent or institute a acknowledgment system.

- The provision of a new AIS interface allowing a better representation of the position of the vessels and the helicopter, thus reducing the workload of the crew.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. They have published: Safety Leaflet HE9 Automation and Flight Path Management

HeliOffshore have published:

- Flight Path Management Recommended Practices

- Automation Guiding Principles

- Automation Training Videos

ESPN-R has published a training guide for hoist operators.

In 2021 the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements, which had included helicopter hoist operations (HHO) from its initial issue in 2015, was expanded to cover Marine Pilot Transfer.

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- BFU Investigate S-76B Descending to 20ft at 40 kts En Route in Poor Visibility

- Technology Friend or Foe – Automation in Offshore Helicopter Operations and Aerossurance Marks RAeS 150th Anniversary by Sponsoring Rotorcraft Automation Conference

- AAIB Report on 2013 Sumburgh Helicopter Accident

- Night Offshore Windfarm HEMS Winch Training CFIT

- SAR Helicopter Loss of Control at Night: ATSB Report

- NTSB Investigation into AW139 Bahamas Night Take Off Accident

- Loss of Control, Twice, by Offshore Helicopter off Nova Scotia

- Loss of Bell 412 off Brazil Remains Unexplained

- NH90 Caribbean Loss of Control – Inflight, Water Impact and Survivability Issues

- Korean Kamov Ka-32T Fire-Fighting Water Impact and Underwater Egress Fatal Accident

- Marine Pilot Transfer Winching Accident: referenced in the Royal College of Art (RCA) & Lloyd’s Register Foundation Safety Grand Challenge: Safe Ship Boarding & Thames Safest River 2030

- SAR Hoist Cable Snag and Facture, Followed By Release of an Unserviceable Aircraft

- TCM’s Fall from SAR AW139 Doorway While Commencing Night Hoist Training

- SAR AW139 Dropped Object: Attachment of New Hook Weight

- Swedish SAR AW139 Damaged in Aborted Take-off Training Exercise

- Tail Rotor Pitch Control Loss During Hoisting

- Night Offshore Training AS365N3 Accident in India

- Firefighting AW139 Loss of Control and Tree Impact

- Fall From Stretcher During Taiwanese SAR Mission (NASC AS365N2 NA-104)

- Fatal Taiwanese Night SAR Hoist Mission (NASC AS365N3 NA-106)

- Dim, Negative Transfer Double Flameout

- Final Report: AS365N3 9M-IGB Fatal Accident

- HF Lessons from an AS365N3+ Gear Up Landing

- UPDATE 8 May 2022: HeliOffshore 2022 Conference Review

- UPDATE 14 May 2022: Review of “The impact of human factors on pilots’ safety behavior in offshore aviation – Brazil”

- UPDATE 5 June 2022: North Sea Helicopter Struck Sea After Loss of Control on Approach During Night Shuttling (S-76A G-BHYB 1983)

- UPDATE 28 December 2022: Night Mountain Rescue Hoist Training Fatal CFIT

- UPDATE 7 January 2023: Blinded by Light, Spanish Customs AS365 Crashed During Night-time Hot Pursuit

- UPDATE 8 July 2023: BK117 Offshore Medevac CFIT & Survivability Issues

- UPDATE 16 July 2023: SAR AW139 LOC-I During Positioning Flight

- UPDATE 13 July 2024: Fatal USCG SAR Training Flight: Inadvertent IMC

- UPDATE 20 July 2024: Night CHC HEMS BK117 Loss of Control

Aerossurance is delighted to sponsor the European Society of Air Safety Investigators (ESASI) Regional Seminar 2022 in Budapest, Hungary 6-7 April 2022.

Recent Comments