When a Crew Intentionally Left Their Aircraft Running Knowing it Would Damage Itself… (RCAF Boeing CH147D Chinook CH147204)

On 18 January 2009 the entire Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) crew intentionally disembarked while rotors running from Boeing CH147D Chinook CH147204 at Kandahar airfield, Afghanistan. When the eventually the abandoned aircraft ran out of fuel the rotors slowed and struck an ad hoc obstacle that had been deliberately placed next the fuselage, causing damage to the main rotor blades and the fuselage.

Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Boeing CH147D Chinook CH147204 at Kandahar Airfield After the Fuel was Exhausted (Credit: DND)

As the crew’s actions were deliberate and the damage from the obstacle strike was intended some might assume this was sabotage. Spoiler: it wasn’t!

The Truth of the Event

The Canadian military summary of their safety investigation explains that the helicopter was on a routine training flight when an aft rotor fixed droop stop was found on the ramp near where CH147204 had been parked. The droop stop constrains the main rotor blades on startup and shutdown to prevent them from contacting the fuselage.

It was quickly established that other nearby aircraft where not missing a droop stop. Operations therefore recalled CH147204. The investigators recount that:

Using a coalition partner’s emergency shutdown procedure; a ramp was built to minimize aircraft damage, the crew set the parking brakes, secured the flight controls in place and exited the aircraft.

This is an excellent example of rapid improvisation in an emergency and collaboratively gathering insight from other stakeholders.

After the engines stopped, due to fuel exhaustion, the rotors began slowing down until they eventually impacted the ramp, causing damage to the rotor blade system and fuselage.

There were no injuries.

The Safety Investigation

The investigators determined that the aft fixed droop stops were “improperly installed”. The inverted fitment caused fatigue of the attachment bolts, resulting in the release of one aft fixed droop stops.

The military investigative summary has relatively few details of that maintenance but comments that:

Contributing factors were the markings “AFT ROTOR BOTTOM” having been applied to the wrong surface, the difficult visual differences between the large and small chamfers (the two bevelled edges of the droop stop block) and ambiguous technical instructions.

The following illustration from US Army Safety of Flight Message CH-47-01-02 shows the chamfers and correct location of marking (though interestingly marking is not universal…).

The investigators note that:

The lack of a rotor brake system also contributed to the degree of aircraft damage.

Consequently:

Safety recommendations include the development of…procedures for droop stop failures applicable to the CH147D Chinook and amendments to the operator’s manual, checklist and technical instructions.

A review of the droop stop [marking] painting process, and the communication of the results of this investigation with…coalition partners is also recommended.

These are all system focused improvements. The ideal improvements, design of a droop stop that could only be fitted one way (rather than reliance of markings and the chamfers) or a droop stop that could be fitted safely in either orientation were presumably considered too expensive to retrofit.

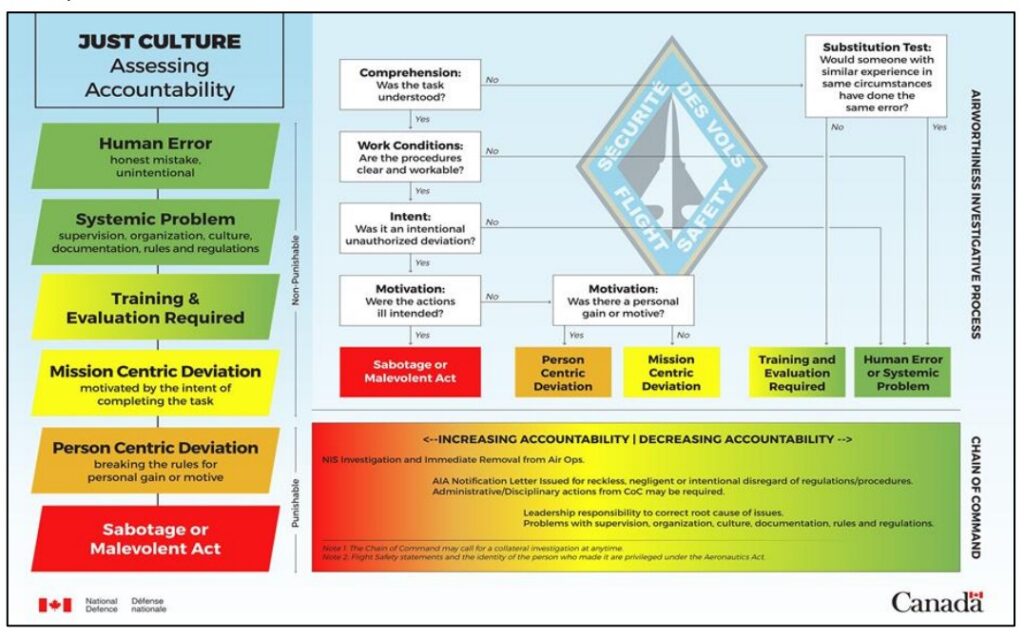

A Discussion on Assessment of Individuals After an Occurrence

This occurrence scenario neatly illustrates the problems with some proprietary ‘just culture’ / culpability / accountability decision aids and their implementation, particularly when the policy is to routinely apply them when reviewing occurrences. Others have observed that “they can be experienced as punishment-first if leadership tone is heavy-handed” and “people watch whether managers are held to the same standard” (which far more rarely occurs).

These tools often overtly label intended actions and intended consequences as sabotage, ignoring the fact that intended actions and intended consequences most commonly feature in safe outcomes!

Then such decision aids typically consider if there had been inattention or indifference to “risk”. Those tools rarely clarify who assessed that benchmark ‘risk’ and when, or indeed if the people involved had the information to make an accurate determination of risk.

Accepting that in this occurrence the Chinook crew were aware that damage was going to ensue, many decision aids would then tend to focus on whether ‘rules’ were disregarded. We have previously commented on US Air Force plans to “significantly reduce unnecessary Air Force instructions over the next 24 months“. The then US Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson for example said USAF documents were “often outdated and inconsistent” and “contain more than 130,000 compliance items at the wing level.” That’s a lot of opportunity for an investigator to find ‘rule breaking’ or a ‘failure to follow procedures (F2FP)’…

Only if no rules were broken do these tools then consider if the personnel involved made an error or a mistake. In this case the crew did neither and their actions resulted in less damage than might have occured in the circumstances the crew found themselves in. These tools, typically seductively simple looking flowcharts, rarely have a route to conclude that personnel performed well (an noticeable exception being a 2008 model by Dr Patrick Hudson et al of Leiden University). This dead-end might imply to the flowchart’s user that the rule breaking / violation route should be explored further.

In this case RCAF had no specific procedures for this type of event and a ‘rule’ undoubtedly existed about not positioning government property were it was going to be damaged. The typical flowchart would then lead to a debate about what type of violation occured (e.g. optimising for organisational gain versus an exceptional violation). Such debate arguably is a distraction from determining effective safety improvements.

Some advocates of these flowcharts might at this point suggest starting the whole process again, this time focusing both on the maintenance personnel who fitted the droop stop and also whoever marked ‘down’ on the wrong side. Other advocates would no doubt recommend readers pay for a 2 day training course on their one page flowchart…

Our readers can however decide if shaking the tree in hunt for ‘bad apples’, rather than focusing on safety improvements, is normally fruitless (pun intended).

There is no discussion the the military summary on if or how the RCAF did do any just culture assessment at the time. The Canadian Department for Defence does now have their own flowchart, which features several relatively unique adaptions.

Firstly the questions sensibly start with determining if the most likely possibilities, namely a simple error or a systemic problem, were involved. That second category provides a way rapidly focus off individuals and onto valuable system improvement.

Secondly the intentions of the individual are only questioned when the task is considered to be understood and the procedures ‘workable’.

In their Flight Safety Manual it is clearly stated that only in “some extreme cases” are actions taken against individuals.

Indeed one RCAF disciplinary case has been recently publicised. In that case the disciplinary action appears specifically related to a false declaration, outside an individual’s scope of authorisation, made after contradictory advice from a relevant specialist, though a number of mitigations were recognised by the Judge.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices The TSB report posses many questions on the management and oversight of aircraft maintenance, competency and maintenance standards & practices. We look at opportunities for forward thinking MROs to improve their maintenance standards and practices.

- Cold Comfort Conference Call: USAF F-35A Alaska Accident A $196.5 mn organisational accident: a conference call and a contaminated barrel.

- The Loss of RAF F-35B ZM152: An Organisational Accident A £81 mn fighter is downed by FOD, one of its own intake blanks. This case study illustrates James Reason’s concept of Organisational Accidents and how just asking “who left the intake blank ?” misses the real reasons behind this accident.

- What a Difference a Hole Makes: E-8C JSTARS $7.35 million Radar Mishap

- USAF Tool Trouble: “Near Catastrophic” $25mn E-8C FOD Fuel Tank Rupture

- Inadequate Maintenance, An Engine Failure and Mishandling: Crash of a USAF WC-130H

- USAF Engine Shop in “Disarray” with a “Method of the Madness”: F-16CM Engine Fire

- Inadequate Maintenance at a USAF Depot Featured in Fatal USMC KC-130T Accident

- BA B747 Landing Gear Failure Due to Omission of Rig Pin During Maintenance

- When Down Is Up: 747 Actuator Installation Incident

- Maintenance Human Factors in Finnish F406 Landing Gear Collapse

- Lost in Translation: Misrigged Main Landing Gear

- Cessna Citation Excel Controls Freeze

- B214ST Tail Rotor Drive Shaft Coupling Misassembly

- Crossed Cables: Colgan Air B1900D N240CJ Maintenance Error

- Crazy KC-10 Boom Loss: Informal Maintenance Shift Handovers and Skipped Tasks

- Frozen Dash 8-100 Landing Gear After ‘Improper Maintenance Practices’ Say NTSB

- ATR 72 Rudder Travel Limitation Unit Incident: Latent Potential for Misassembly Meets Commercial Pressure

- Loose B-Nut: Accident During Helicopter Maintenance Check Flight

- USAF RC-135V Rivet Joint Oxygen Fire

- CHC Sikorsky S-92A Seat Slide Surprise(s)

- SAR AS365N3 Flying Control Disconnect: BFU Investigation

- In-Flight Flying Control Failure: Indonesian Sikorsky S-76C+ PK-FUP

- AAR Bell 214ST Accident in Afghanistan in 2012: NTSB Report

- Misassembled Anti-Torque Pedals Cause EC135 Accident

- EC130B4 Accident: Incorrect TRDS Bearing Installation

- Ungreased Japanese AS332L Tail Rotor Fatally Failed

- R44 Ditched After Loss of TGB & TR: Improper Maintenance

- Missing Cotter Pin Causes Fatal S-61N Accident

- Emergency S-76D Landing Due to Fumes

- Engine & Emergency Flotation Failures – Greenland B206L4 Ditching

- The Missing Igniters: Fatigue & Management of Change Shortcomings

- FAA Rules Applied: So Misrigged Flying Controls Undetected

- BEA Point to Inadequate Maintenance Data and Possible Non-Conforming Fasteners in ATR 42 Door Loss

- BA A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Report

- BA A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Safety Recommendation Update

- ANSV Report on EasyJet A320 Fan Cowl Door Loss: Maintenance Human Factors

- Tiger A320 Fan Cowl Door Loss & Human Factors: Singapore TSIB Report

- Human Factors of Dash 8 Panel Loss

- Fuel Tube Installation Trouble

- How One Missing Washer Burnt Out a Boeing 737

- Flying Control FOD: Screwdriver Found in C208 Controls

- Cessna 208 Forced Landing: Engine Failure Due To Re-Assembly Error

- Meeting Your Waterloo: Competence Assessment and Remembering the Lessons of Past Accidents

You might find these safety / human factors resources of interest:

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- This 2006 review of the book Resilience Engineering by Hollnagel, Woods and Leveson, presented to the RAeS by Aerossurance’s Andy Evans: Resilience Engineering – A Review and this book review of Dekker’s The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error: The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

- Airworthiness Matters: Next Generation Maintenance Human Factors

In 2022 the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) launched the Development of a Strategy to Enhance Human-Centred Design for Maintenance. Aerossurance‘s Andy Evans is pleased to be involved in this initiative.

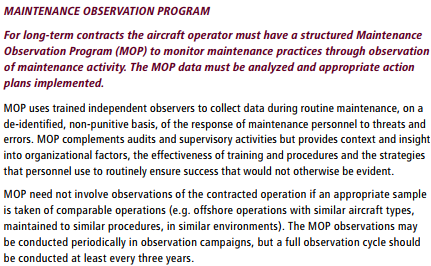

FSF Maintenance Observation Programme (MOP)

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement in 2016 for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help provide insights into routine maintenance, the response to threats and errors, the strategies taken to routinely ensure success and to initiate safety improvements:

Aerossurance can provide practice guidance and specialist support to successfully implement a MOP.

Recent Comments