Improvised Ice Road IMC Approaches – Twin Otter CFIT (Air Tindi C-GMAS)

On 27 December 2023, Air Tindi De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 C-GMAS crashed into the crest of a snow-covered hill during an approach to an ad hoc airstrip at the Lac de Gras road camp, Northwest Territories during a visual flight rules flight. The two pilots and 8 passengers survived, two with serious injuries

Wreckage of Air Tindi Twin Otter C-GMAS After CFIT near Lac De Gras, NT the Morning After (Credit: Department of National Defence via TSB)

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) released their safety investigation report on 8 January 2026.

Air Tindi was founded in Yellowknife, in 1988 and operates a fleet of 17 single- and multi-engine turboprop aircraft according to the TSB.

The Accident Flight

That morning the Twin Otter had flown from Yellowknife, to Margaret River and was to fly on to Lac de Gras, near the Diavik diamond mine site, before returning to Yellowknife. The aircraft was transporting Tibbitt to Contwoyto ice road construction workers and supplies to temporary camps at Margaret Lake and Lac de Gras.

The Aircraft Commander (who had c14,300 total hours, c 8,000 on type) would be the Pilot Flying (PF) for the first 2 legs (i.e. to the two ad hoc air strips), and the co-pilot (c400 total, c 200 on type) would be the Pilot Monitoring (PM). The FO was a former dispatcher with the operator, who became a part-time FO on the Twin Otter on 1 August 2023 (5 months before) and only started a full-time flying position on 17 November 2023 (c 6 weeks before).

The aircraft was equipped with 2 Garmin GNS 430W GPS (global positioning systems) with a limited moving-map showing large bodies of water, terrain outlines, and real-time aircraft position. The aircraft was also equipped with a Garmin Flight Stream 210, which allows position information from the Garmin GNS 430W to be broadcast to the flight crew’s [Electronic Flight Bags] EFBs and the ForeFlight Mobile application.

While en route to the two ad hoc landing sites, TSB say that…

… to prevent unwanted terrain warning…the flight crew disabled the aircraft’s [Sandel ST3400] terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS) by pulling the circuit breaker.

While the Sandel ST3400…

… provides a TAWS INH (inhibit) function that cancels all forward-looking terrain avoidance and premature descent alerts but does not cancel basic ground proximity warning system alerts. Given the distraction caused by having both cautions and warnings activated during off-strip landings, Twin Otter pilots at Air Tindi would disable the TAWS by pulling the circuit breaker.

TSB comment that:

At various times throughout the 1st leg and early in the occurrence flight (2nd leg), the flight crew identified the challenging weather conditions; however, their identification of the threat posed by the weather never reached a threshold where it was felt that they could not successfully complete the flight.

At 1223, approximately 10 NM from the Lac de Gras road camp, the crew received the following weather report from the nearby Diavik mine site airfield:

- Winds from 300° true (T) at 25 knots, gusting to 32 knots

- Visibility of ½ SM in blowing snow

- Altimeter setting of 29.20 inHg

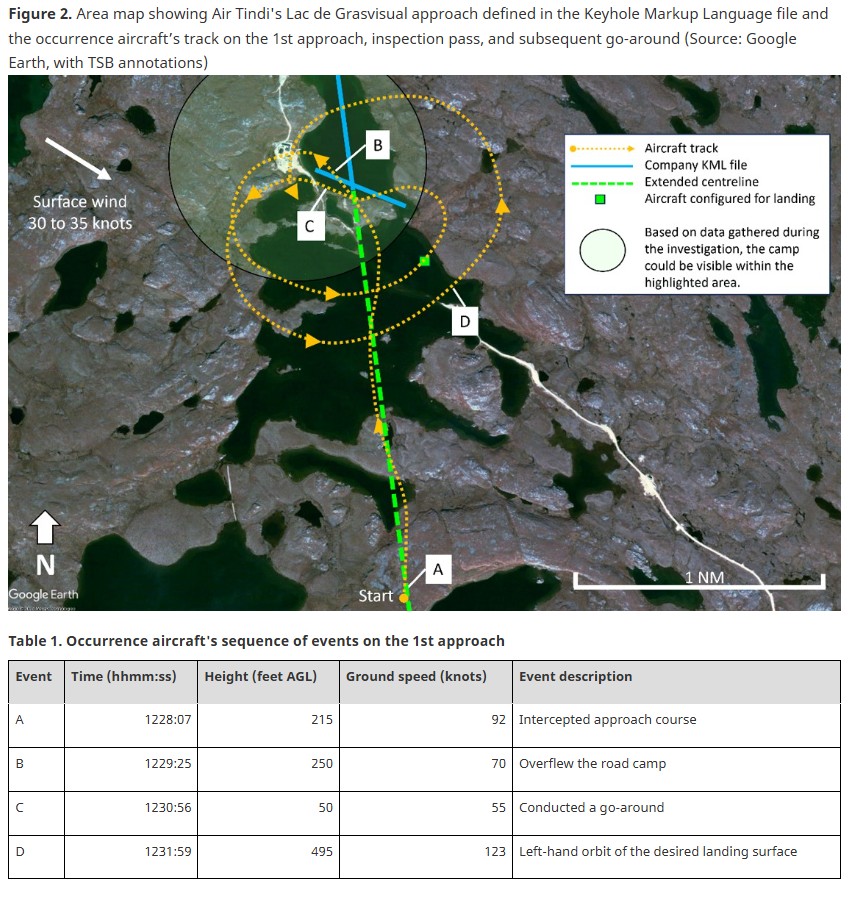

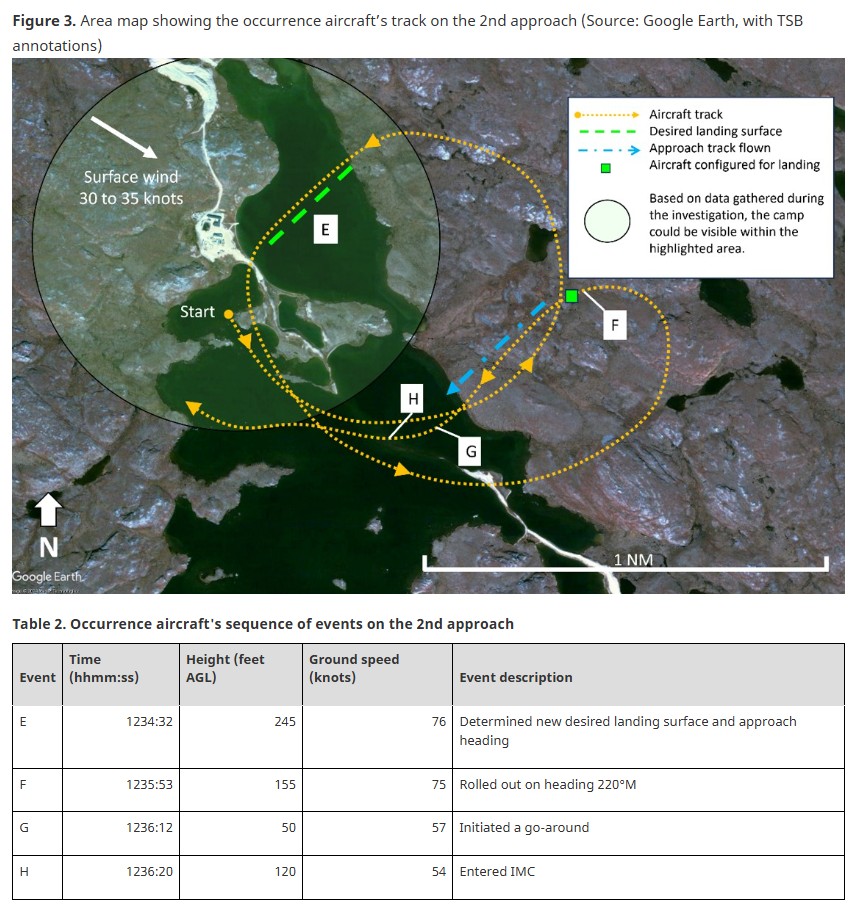

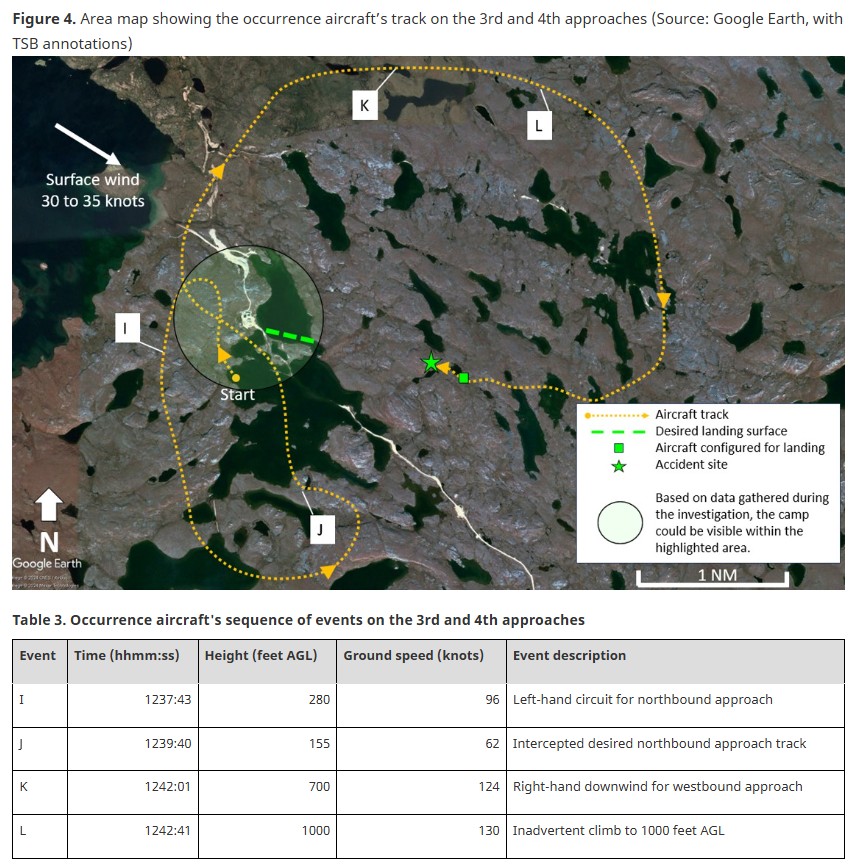

Upon arriving over the Lac de Gras road camp, the flight crew conducted 4 approaches toward the desired landing area on the frozen lake surface, descending at times to heights below 50 feet above ground level.

At the time of the 4th approach, the visibility was approximately ½ SM.

When the aircraft rolled out on final, it was approximately 2 NM from the road camp and at 150 feet AGL.

After establishing the aircraft on the final approach course, the flight crew relied on the EFB guidance to determine their position relative to the desired landing path. The aircraft continued to descend to approximately 50 feet AGL on the final approach course. The PM was verbally providing lateral guidance to the PF based on the track on his EFB.

At 1245:20, the aircraft was configured for landing (green square on Figure 4). When the aircraft was 1.5 NM from the desired landing surface, the PF descended below 50 feet AGL in anticipation of landing.

Moments later:

At 1245:28, both flight crew members saw a hill in the windscreen. The PF applied full power, and both pilots pulled aft on the yoke to initiate a pitch up. The last recorded ground speed of the aircraft was 44 knots. The aircraft impacted the terrain 2 seconds later at 1245:30.

Two passengers were seriously injured and were unable to egress. The remaining occupants, including one passenger who was ejected, sustained minor injuries. There was no post impact fire.

The emergency locator transmitter activated, and [3 parachuted] search and rescue personnel from the Canadian Armed Forces and a volunteer search party from Diavik mine…arrived on the scene 8 hours after the occurrence.

The following morning, all but the volunteer search party were flown [by helicopter] to Diavik Aerodrome (CDK2)…and subsequently to Yellowknife Airport (CYZF)…

TSB Safety Investigation 1: Wreckage, Survivability & Recorders

The wreckage was located on the crest of a snow-covered hill in a nose-high attitude with the rear half of the aircraft overhanging the edge.

Wreckage of Air Tindi Twin Otter C-GMAS After CFIT near Lac De Gras, NT (Credit: Operator via TSB)

There was considerable damage to the underside of the fuselage; both main landing gears collapsed and the nose gear compressed into the fuselage. The right-hand engine separated at the power turbine, with the hub and propeller left loosely attached.

TSB note that:

Given the relatively slow approach speed of the Twin Otter and the strong head wind on the final attempt to land, all occupants survived the impact with the hill.

Meanwhile:

The emergency mode on the aircraft SKYTRAC ISAT-200A tracking system was activated by the FO at 1247:50, notifying Air Tindi of the accident. The Canadian Mission Control Centre (CMCC) in Trenton, Ontario, received an emergency locator transmitter (ELT) signal from the aircraft on the 406 MHz frequency at 1248.

The aircraft’s sat phone could not be used as it had to be connected to a pilot headset (and both were damaged on impact). A passenger was able to make a mobile phone call.

The aircraft’s survival kit was difficult to access as it was in the aft baggage bay, overhanging the edge of the hill. It had a tent that was too small for the number of occupants aboard and two tarpaulins that were difficult to rig in open terrain and uninsulated. In the absence of vegetation for a fire, the survivors only had the survival kit candles which not surprisingly were not a suitable source of warmth. TSB comment:

Because the survival equipment required by regulation is open to interpretation, it may be insufficient to provide the necessities needed by survivors after an accident, creating a risk that passengers and pilots will be unable to survive in the environment.

Air Tindi did have more comprehensive kits, but these were typically only carried on multiday deployments,

TSB note that:

The aircraft was not equipped with a flight data recorder, nor was it required by regulation.

However, the aircraft was equipped with an automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast system, which provided the investigation with significant information about the flight path of the aircraft, including the altitude, the track, and the ground speed.

The aircraft was also equipped with a CVR that had a recording capacity of 120 minutes. The CVR data was successfully downloaded…,included both flights on the date of the occurrence and contained good quality audio.

TSB Safety Investigation 2: The Approach, Navigation, TAWS & CFIT Training

Air Tindi used Keyhole Markup Language (KML) imported into ForeFlight, available on iPad Mini EFBs, to add a layer of labelling to existing maps.

The company-created KML files are intended to be used as guidance during VFR approaches to locations without certified approach procedures, allowing pilots to line up on final with off-strip locations from a greater distance than if only visual navigation was used. The KML files also allow for better situational awareness while circling in relatively featureless terrain, providing a PM with a constant visible track on their EFB. The KML file for the Lac de Gras road camp displayed 2 landing areas on the lake, one in a northwest to southeast direction and one in an east-west direction.

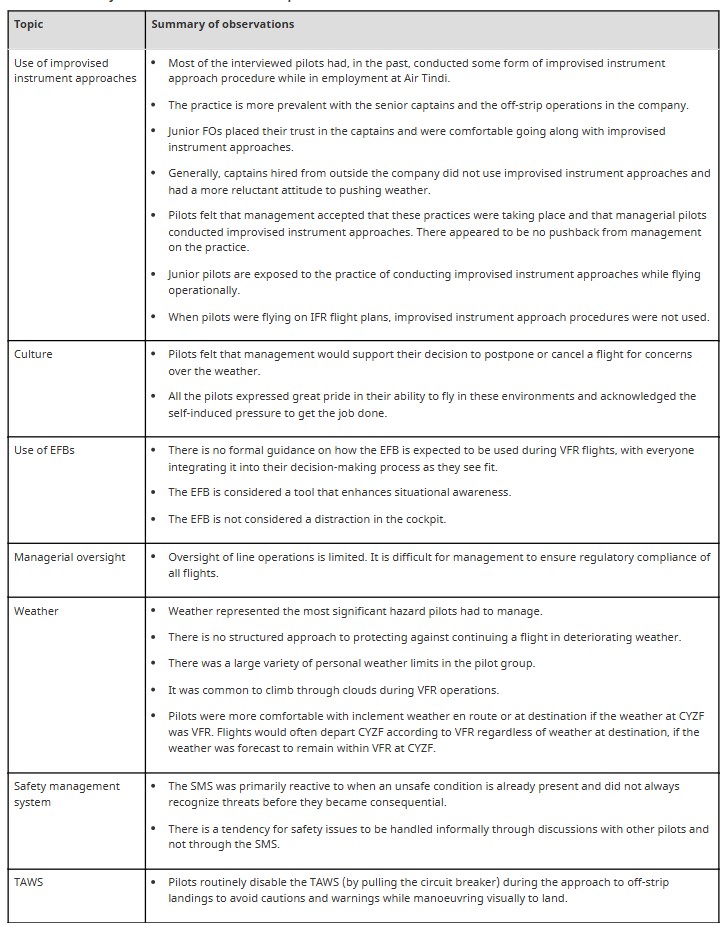

Many pilots reported that most of the functionality of the EFBs is learned while flying with more experienced pilots or by experimenting with the EFBs on their own.

With this approach, the…

…pilots felt comfortable creating their own safety envelope outside of the current regulations.

In the case of this accident:

…the flight crew frequently relied upon the EFBs as their primary source of navigation guidance.

However:

Using EFBs as a primary source of navigation guidance to fly in IMC is not a standardized procedure; it has not been formally risk assessed in any way by Air Tindi nor Transport Canada, and more importantly, it is not permitted by regulations.

There is no training or guidance provided by Air Tindi on how the company expects the GPS and auxiliary navigation functionality available in ForeFlight to be used or integrated into in-flight decision making by pilots.

In relation to TAWS:

Following discussions with 11 Air Tindi pilots, the investigation determined that there was no common procedure on when to disable the TAWS. The company does not provide any guidance on whether or when the TAWS should be disabled.

Inhibiting TAWS could have been left to the approach briefing to minimise the loss of protection but…

…the flight crew did not conduct any formal approach briefing or associated threat review [as described in the Air Tindi procedures].

TSB note that the ad hoc camp airstrip had no instrument approach procedures and…

A practice adopted by Air Tindi pilots at the time of the occurrence was to set the radio altimeter to aid with conducting an improvised [i.e. uncertified] instrument approach to a lower altitude than a minimum IFR altitude. The common practice at Air Tindi was to set 500 feet on the radio altimeter as an acceptable descent altitude for regions in the tundra, where terrain height does not vary drastically, and man-made structures do not exceed that height. Pilots would fly in IMC down to the height above ground level set in the radio altimeter in a manner similar to a minimum descent altitude on published non-precision approaches. Several Air Tindi pilots also expressed that setting the descent altitude below 500 feet on the radio altimeter was also a common practice if they felt that terrain was not a factor.

However in this case…

…the radio altimeter was set to 200 feet AGL.

Air Tindi provided CFIT training, but simply as an online course.

Remarkably, nowhere in the report do TSB comment on the absence of a stabilised approach and the associated ‘gates’ where a PM would call for a go-around (a key PM role on approach). A reader could infer that the custom and practice was not to apply such procedures to landing at ad hoc airstrips.

TSB Safety Investigation 3: Oversight, SMS, Culture & Practice

Due to the size of the aircraft in their fleet (<27 t) Flight Data Monitoring (FDM) was not required by regulation so readers will be pleased that TSB report:

Air Tindi also uses a flight operations quality assurance (FOQA) program to aid in providing oversight on flights. At the time of the occurrence, there was an FOQA coordinator, who reported to the SMS [safety management system] manager.

FOQA is frequently used as a alternative term to FDM, especially in the US.

However TSB explain that…

…the FOQA program did not utilize FDM. The FOQA coordinator position largely entailed assisting in preparing the company for audits (client, regulator, and internal) and occasionally aiding the SMS manager with investigations if required.

TSB interviewed Air Tindi Twin Otter pilots to better understand the day-to-day practices of line pilots:

TSB explain that:

The SMS at Air Tindi is used to report operational occurrences that affected the flight but is generally not used to identify possible safety deficiencies.

As in a previous Air Tindi occurrence [C-GSPN on 1 November 2021: “in which a Twin Otter departed without sufficient fuel to complete the flight resulting in fuel starvation and landing off-airport”], the investigation into the current occurrence did not identify any SMS reports relating to unsafe practices, despite these practices being identified by every pilot interviewed during the investigation.

Air Tindi Twin Otter C-GPNS near Fort Providence, NT, 1 November 2021 after Fuel Exhaustion (Credit: Operator via TSB)

In the 2021 accident the aircraft commander had 6,397 total hours (2,945 on type) but the co-pilot had only 435 (89 on type), and had joined the company just 8 weeks earlier.

In the 1 November 2021 accident (our emphasis added) junior first officers…

…were aware, and had discussed amongst themselves, that when flying with some of the senior captains, these captains had adopted the practice of performing some of the verbal challenge and response checklists silently, by memory only and by themselves, i.e., without necessarily the input or challenge from the first officer.

Non-verbalised checklists subverts the value of the Pilot Monitoring role in monitoring the Pilot Flying. The FOs did not report this issue but instead (our emphasis added)…

…had informally discussed the checklist practice with some of the training captains on the DHC-6. Because safety reports were not submitted on this issue, company management, as a whole, was not fully aware of the issue.

In the latest report TSB comment (our emphasis added):

Operational issues are often dealt with less formally rather than through the SMS, with pilots discussing issues with their superiors (assistant chief pilots, chief pilot) and the issues being dealt with through informal meetings and by word of mouth.

While an active safety dialogue is good, identifying trends, capturing lessons learnt, following actions to a conclusion and so on suffers without a record (as noted in a fatal 2017 helicopter CFIT accident).

It is noteworthy that the 1 November 2021 accident report was issued on 24 November 2022, 13 months prior to the Lac de Gras accident and it contained no indication of any action by Air Tindi on safety reporting, even though the TSB comment that the internal investigation also identified this. It is suggested in a press report that TSB don’t assess the actions taken, but simply list them. If true that is a missed opportunity.

Later in the lates report TSB add (again with our emphasis added):

…pilots who experienced deviations from company SOPs or from published procedures tended to talk informally to the senior captains rather than use the SMS.

Elaborating on the organisation culture, TSB shed further light on this informal tutoring (our emphasis again)…

The investigation determined that pilots at Air Tindi demonstrated a goal-oriented attitude toward decision making and took great pride in completing their flights in challenging operational environments and generally accepted deviation from published procedures.

The investigation also determined that the FOs [First Officers] at Air Tindi revere the experienced off-strip captains and hold them in high regard and may sometimes succumb to the halo effect during VFR flights in inclement weather.

In particular:

The FOs are generally very new to the aviation industry and often rely on the captains to determine what are acceptable practices in the organization and the industry.

In this case the crew had an c14,300 to 400 hour cockpit gradient. Concerningly:

The FOs would not voice concerns about unsafe practices such as flying VFR in IMC to the captains because there was a perceived notion that “this is how it’s done” when flying in the north.

A point that TSB miss is that therefore these young FOs will find it very difficult to challenge the PF when they are the PM, further subverting the value of the Pilot Monitoring role.

The investigators observe that:

The occurrence captain’s extensive experience in the air-taxi sector likely altered his perception of risk over time, leading him to adopt a higher-risk threshold for weather limits. This made him confident that the day’s flights could be completed despite the challenging weather conditions, which contributed to the decision to make the flight and try to land at Lac de Gras.

However, past success is not a guarantee of future successful performance…

TSB note that consequently there was…

….a gap between the procedures that Air Tindi has laid out with regards to weather limits and the practices that are enacted by pilots.

Even though Air Tindi has an SMS, unsafe practices were accepted by pilots and were viewed as part of normal work; these practices never triggered an SMS report or generated more significant action from company management to address the issues.

Air Tindi had a hazard register as part of its SMS but surprisingly for their type of operation…

…the hazard of continuing VFR flights into IMC was not a documented hazard that was formally tracked or managed.

TSB do no elaborate why this hazard was not listed. One reason some operators have major omissions is they only assess hazards once they are identified in their own safety reports.

In this case TSB comment that:

Air Tindi pilots have accepted unsafe practices as being normal work and therefore no longer perceive the risks in these practices.

Training has no impact on these practices that are not formalized procedures. Instead, these practices are learned and proliferated through informal operational learning during flights.

TSB do make a ‘finding as to risk’ that:

If air operators do not utilize the FDM capabilities available to them, they can miss opportunities to ensure the effectiveness of and adherence to published procedures, increasing the risk of an accident.

However, TSB missed the opportunity to issue a safety recommendation on FDM and to identify LOSA as another way to unearth unsafe practices.

TSB do however observe that the oversight by the regulator, Transport Canada disappointingly…

…focused more on how the documented processes (e.g., SOPs, SMS manual, etc.) look in relation to the regulatory framework, than on how the processes are being conducted day-to-day.

They insightfully comment that:

An approach to regulatory surveillance heavily weighted to auditing documented processes and procedures will result in a narrow view of how companies are managing safety in their operations…

Adding:

If…air operators are only required to respond to findings of regulatory non-compliance and are not required to respond to observations regarding non-compliance with their own manuals, programs, systems, processes and procedures, or with published industry safety standards, there is a risk that safety deficiencies…will persist.

TSB Findings as to Causes and Contributing Factors

- The oversight mechanisms employed by Air Tindi were unable to detect the drift away from standard operating procedures, and deviations by pilots, including the conduct of improvised instrument approaches in instrument meteorological conditions, were not addressed.

- The flight crew’s decision to depart on the day’s flights and continue flying in deteriorating weather was influenced by both the flight crew’s past successful experiences in similar conditions and by a plan continuation bias, which led to a reduced perception of risk associated with continuing this visual flight rules flight in instrument meteorological conditions.

- The flight crew’s overreliance on the electronic flight bags for situational awareness contributed to their decision to continue operating visually in instrument meteorological conditions.

- While conducting an improvised instrument approach in an area of reduced visibility, the flight crew intentionally descended below 50 feet above ground level without sufficient visual reference to the surface and the aircraft impacted rising terrain.

TSB Findings as to Risk

- Operating an aircraft in instrument meteorological conditions at altitudes below the minimums established for instrument flight rules increases the risk of controlled flight into terrain.

- If air operators do not provide formal guidance on the use of company-made visual flight rules approach procedures, there is a risk that flight crews will use these approaches in instrument meteorological conditions and elevate the risk of controlled flight into terrain.

- Intentionally disabling an aircraft’s terrain awareness and warning system eliminates a critical safeguard designed to warn pilots of an impending controlled flight into terrain.

- If air operators do not utilize the flight data monitoring capabilities available to them, they can miss opportunities to ensure the effectiveness of and adherence to published procedures, increasing the risk of an accident.

- The current approach to surveillance employed by Transport Canada relies heavily on examining an air operator’s documented processes, versus conducting observations of operations, when assessing regulatory compliance. This makes it difficult for Transport Canada to detect drifts from current regulations, which may reduce safety margins to unacceptable levels.

- If, following regulatory surveillance, air operators are only required to respond to findings of regulatory non-compliance and are not required to respond to observations regarding non-compliance to their own manuals, programs, systems, processes and procedures, or with published industry safety standards, there is a risk that safety deficiencies that were identified during the surveillance will persist.

- If regulations or regulatory guidance are slow in adapting to changing technology that impacts critical operational areas, there is a risk that this technology will be used in ways affecting the safe operation of aircraft.

- Because the survival equipment required by regulation is open to interpretation, it may be insufficient to provide the necessities needed by survivors after an accident, creating a risk that passengers and pilots will be unable to survive in the environment.

Safety Actions

Air Tindi told TSB they had taken the following actions:

- Increased weather limitations on all flights with featureless terrain.

- Implemented mandatory pilot monitoring requirements and actions by the first officer for all off-strip approaches and landings.

- Conducted one-on-one conversations with each captain at Air Tindi regarding company culture, standards, human factors, and threat-based decision making over goal-based decision making.

- Enhanced crew resource management training to address culture and behaviour change.

- Implemented co-authority dispatch to all operations to address a culture and behaviour change.

- Implemented a Flight Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) to better evaluate risks prior to dispatch.

- Increased simulator training to address the needed culture, behaviour change, and experience gradient in the cockpit.

- Reviewed the list of survival equipment included in survival kits and upgraded the contents to ensure that the effectiveness of the survival gear matches the environment and risk.

- Upgraded all aircraft instrumentation to increase situational awareness.

The last item was reportedly a CAN$8 million investment. Cockpit upgrades to their Dash 7 fleet have been publicised.

No safety recommendations were raised by TSB.

Safety Resources

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns

- Helicopter Water Impact Accident: Safety of Airborne Geophysical Survey Operations

- Crew Confusion in Firefighting 737 Terrain Impact

- Startled Shutdown: Fatal USAF E-11A Global Express PSM+ICR Accident

- ‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

- Oil & Gas Aerial Survey Aircraft Collided with Communications Tower

- The Loss of RAF F-35B ZM152: An Organisational Accident

- Loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230 and the Haddon-Cave Review

- RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

- MC-12W Loss of Control Orbiting Over Afghanistan: Lessons in Training and Urgent Operational Requirements

- A Second from Disaster: RNoAF C-130J Near CFIT

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- Fatal 2019 DC-3 Turbo Prop Accident, Positioning for FAA Flight Test: Power Loss Plus Failure to Feather

- DA62 Forced Landing After Double Engine Shutdown Due to Multiple Electrical Issues

- “Sensation Seeking” Survey Fatal Accident

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- Canadian Mining Air Accident (Cessna 208B Caravan)

- Wait to Weight & Balance – Lessons from a Loss of Control

- Impromptu Flypast Leads to Disaster

- Catastrophe in the Congo – The Company That Lost its Board of Directors

- Wake Turbulence Diamond DA62 Accident in Dubai

- DC3-TP67 CFIT: Result-Oriented Subculture & SMS Shelfware

- Disorientated Dive into Lake Erie

- Cessna 208B Collides with C172 after Distraction

- Business Jet Collides With ‘Uncharted’ Obstacle During Go-Around

- Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I

- US Dash 8-100 Stalled and Dropped 5000 ft Over Alaska

- Saab 2000 Descended 900 ft Too Low on Approach to Billund

- Visual Illusions, a Non Standard Approach and Cockpit Gradient: Business Jet Accident at Aarhus

- NTSB Report on Miami Air International Jacksonville B737-800 Runway Excursion

- ERJ-190 Flying Control Rigging Error

- ATR 72 Rudder Travel Limitation Unit Incident: Latent Potential for Misassembly Meets Commercial Pressure

- Aborted Take Off with Brakes Partially On Results in Runway Excursion

- Easyjet A320 Flap / Landing Gear Mis-selections

- Wrong Engine Shutdown Crash: But You Won’t Guess Which!: BUA BAC One-Eleven G-ASJJ 14 January 1969

- Premature A319 Evacuation With Engines Running

- G200 Leaves Runway in Abuja Due to “Improper” Handling

- Global 6000 Crosswind Landing Accident – UK AAIB Report

- Challenger Damaged in Wind Shear Heavy Landing and Runway Excursion

- Runaway Dash 8 Q400 at Aberdeen after Miscommunication Over Chocks

- Misted Masks: AAIB A319 Report Reveals Oxygen Mask Lessons

- Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- ANSV Highlight Procedures & HF After ATR72 Landing Accident

- Safety Lessons from TransAsia ATR-72 Flight GE222 CFIT

- Unalaska Saab 2000 Fatal Runway Excursion: PenAir N686PA 17 Oct 2019

- Double Trouble: Offshore Surveillance P68 Forced to Glide

- Poor Contracting Practices and a Canadian Helicopter HESLO Accident

- Flat Light B206L4 Alaskan CFIT & 11 Hour Emergency Response Delay

- Canadian Flat Light CFIT

- RCMP AS350B3 Left Uncovered During Snowfall Fatally Loses Power on Take Off

- EC130B4 Destroyed After Ice Ingestion – Engine Intake Left Uncovered

- Inexperienced IIMC over Chesapeake Bay: Reduced Visual References Require Vigilance

- Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident

- Sécurité Civile Fatal EC145 CFIT: Night, Low Ceiling and a Change in Route

- Heliski Flat Light Flight into Terrain

Recent Comments